For thousands of years people from all over the world have eaten insects. Today about 2.5 billion people—many of whom live in Africa—eat insects. To date, 470 African edible insects have been scientifically recorded, with grasshoppers and termites among some of the favourites.

There are many reasons why we should be eating insects. They support a “greener” lifestyle for meat eaters. Of the total greenhouse gases each year at least 15 per cent comes from livestock. For their part insects produce 1kg to 3kg less greenhouse gases per kilo. They also need between 40 per cent and 80 per cent less feed per kg than livestock and anywhere from 50 per cent to 90 per cent less acreage to produce one kg of protein than beef —depending on the insect species and farming method used. That’s great news in a world battling scarce land and water resources.

Insects are also nutritious. Many insect species contain relatively more protein than conventional meat sources, like chicken or pork. Insects also contain essential fatty acids and important minerals and vitamins. For example, termites, when dried, contain up to 36 per cent protein.

We need to rethink our diets and food habits, in particular those related to meat consumption. Because insects are an affordable and local food source rich in protein, they can be used as a meat replacement. To help in this, we put together a guide on how insects can be eaten. To collect the most authentic, flavourful and varied recipes we visited villages in rural areas and spoke to local cooks about how to prepare their favourite specialties.

Insect recipes

It’s important to prepare the insects properly before eating:

-

Wash the insects

-

Boil, steam or fry them for at least five minutes

-

Eat the prepared insects directly after cooking

-

If not eaten immediately, the insects must be preserved. Either keep them in a fridge or freezer, or sun-dry them to preserve them. They can last for a few days.

In the tropics, insects are mainly harvested in the wild so those steps are important. But some of these insects are now available in Western supermarkets. Here are a few recipes to get you started:

Termites (nemeneme)

Termites are one of the tastiest forms of protein available on the planet. Termites are best toasted or lightly fried until they are slightly crisp. Since their body is rich in oil, very little or no additional oil is needed.

Soldier termites can be coaxed from their tunnels by probing their mounds with long reeds which they clamp onto.

They can be preserved by dry frying in salt until they are crispy. They can then be made into a stew with tomato, onion and whatever spices you like.

Flying termites are traditionally caught by placing pots of water under lights, which attract them.

Thief ants (dinhlamakura)

These huge black ants only appear above ground once a year, just after the first rains, when they leave their nests to mate, reproduce and start new underground colonies.

Also called “big bottom” ants, they are prized for their rich taste. They can be eaten raw—their fat abdomens bitten off, discarding the head and legs. But they do very well as a fatty snack, like peanuts. For this, they should be lightly fried with salt.

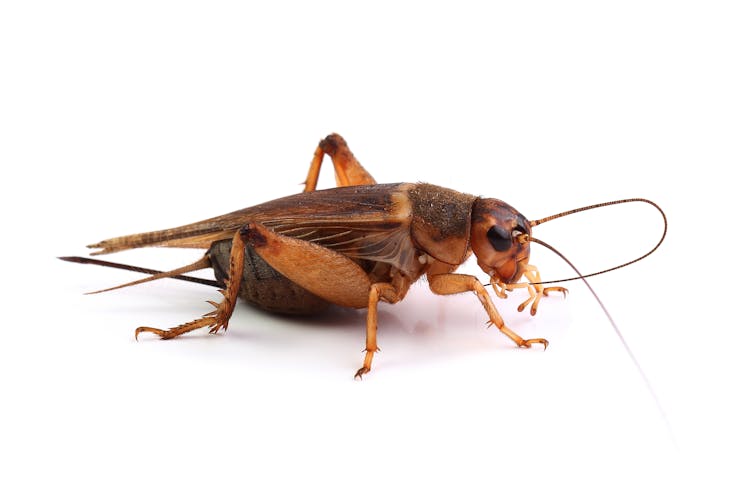

House cricket

Grilled house cricket snack:

These insects are great with sesame oil. Remove wings and mix them with a few drops before putting them under an oven grill for about ten minutes, until they become crispy. Another preparation is to fry the wingless crickets in a few drops of sesame or olive oil for about ten minutes until crispy.

House crickets and dates:

The crickets can also be used to stuff dates —a beautiful contrast with the sweet date and nutty insect. Cut the dates open from the side, remove the pit, and fill with fresh or frozen crickets.

Caterpillars (Cirina forda)

These caterpillars can be collected from Burkea africana trees, which are found in most African countries.

When home, rinse with fresh water. Their innards need to be squeezed out —this is because they contain their food plant which is indigestible. Then boil them for 30 minutes in salted water. After boiling, spread them out on a tray and leave them in the sun. Allow them to bake in the sun for one or two days until crisp. If cooked over a fire they develop a distinct and tasty smoky flavour—like biltong.

They can then be eaten as a snack or prepared as a stew. To make the stew, fry them in oil with chill and garlic. Add tomato, onion and capsicum and allow them to stew for 15 minutes. They go really well with rice or pap, a cornmeal porridge.

Long-horned grasshopper

These grasshoppers have long been part of the food culture in the Lake Victoria region of East Africa. They are most commonly green or brown. Collection is easy because the insects are attracted to light in the evenings.

Pull the wings off and eat them raw. But if you prefer to cook them, they can be either boiled or fried.

Mopane worms

After harvesting the mopane worms, squeeze out their guts starting from the head. Wash the mopane worms in cold water and then boil them for about 15 minutes. Add salt to taste. Allow them to cool and put them out in the sun for a few days, or smoke them until they are completely dry.

Dried mopane worms can be eaten as snacks with or without porridge, or cooked again. To cook dried mopane worms; soak one cup of dried mopane worms in hot water for about 30 minutes. Rinse them in cold water. Put them in a pot with half a fried onion, 2 tomatoes, curry and green pepper. Add half a cup of water and a half teaspoon of soft salt, and mix. Boil for about 20 minutes.

Free of hormones, home grown, organic and free range; insects should be high on any health fanatic’s diet list.![]()

Martin Potgieter, Professor, Department of Biodiversity, University of Limpopo and Bronwyn Egan, Lecturer and PhD candidate, Department of Biodiversity, University of Limpopo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.