Even if the world is successful in meeting its most ambitious climate goal of 1.5C, glaciers could lose a quarter of their total mass by 2100 – raising global sea levels by 90mm.

The world is not currently on track for 1.5C. The research finds that country promises made at the COP26 climate summit in 2021, which could lead to 2.7C of warming, would cause “the near-complete deglaciation of entire regions” including central Europe, western North America and New Zealand.

If global warming reaches 4C, 83 per cent of the world’s glaciers could disappear, the study adds.

As well as providing most of the world’s freshwater, glaciers support unique ecosystems and are considered sacred in many parts of the world.

The research, published in Science, is the first to examine the likely fate of all 215,000 of the world’s glaciers using high-resolution modelling.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, a leading glaciologist not involved in the study described the “sobering” findings as “the most comprehensive and rigorous analysis of future glacier trends to date”.

Disappearing deities

Glaciers are slow-moving rivers of ice which play a key role in supplying freshwater to nearly every world region.

For many communities, from the Peruvian Andes to the Nepalese Himalayas, glaciers are also considered the home and physical manifestations of the gods – holding significance far beyond material value.

Human-caused climate change is already causing widespread glacier decline, with the rate of loss accelerating in the last two decades.

“

Significant loss of glaciers means that we are not only witnessing a change in landscape or a loss of natural resources, it means that we are actively complicit in robbing the future from our children. What are mountain peoples without the mountains as we know them?

Dr Pasang Sherpa, anthropologist, University of British Columbia

The new research uses advanced models to project changes to all of Earth’s 215,000 glaciers from 2015 to 2100 under a wide range of scenarios – from a future where global warming is successfully kept at 1.5C to a world where temperatures hit 4C.

The results say that, if warming is kept to 1.5C, 49 per cent of glaciers could disappear entirely by 2100 – with “at least half” of such losses occurring before 2050. Glaciers are also projected to lose a quarter of their mass, causing sea levels to rise by 90mm.

At 4C, 83 per cent of glaciers could be lost. At this level of warming, glaciers are projected to lose 41 per cent of their mass, raising sea levels by 154mm.

Study lead author Dr David Rounce, an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, tells Carbon Brief:

“A key finding was that the mass loss was linearly related to temperature increases and thus any reduction in the temperature increase will considerably reduce glacier mass loss and its contribution to sea level rise.”

Charting change

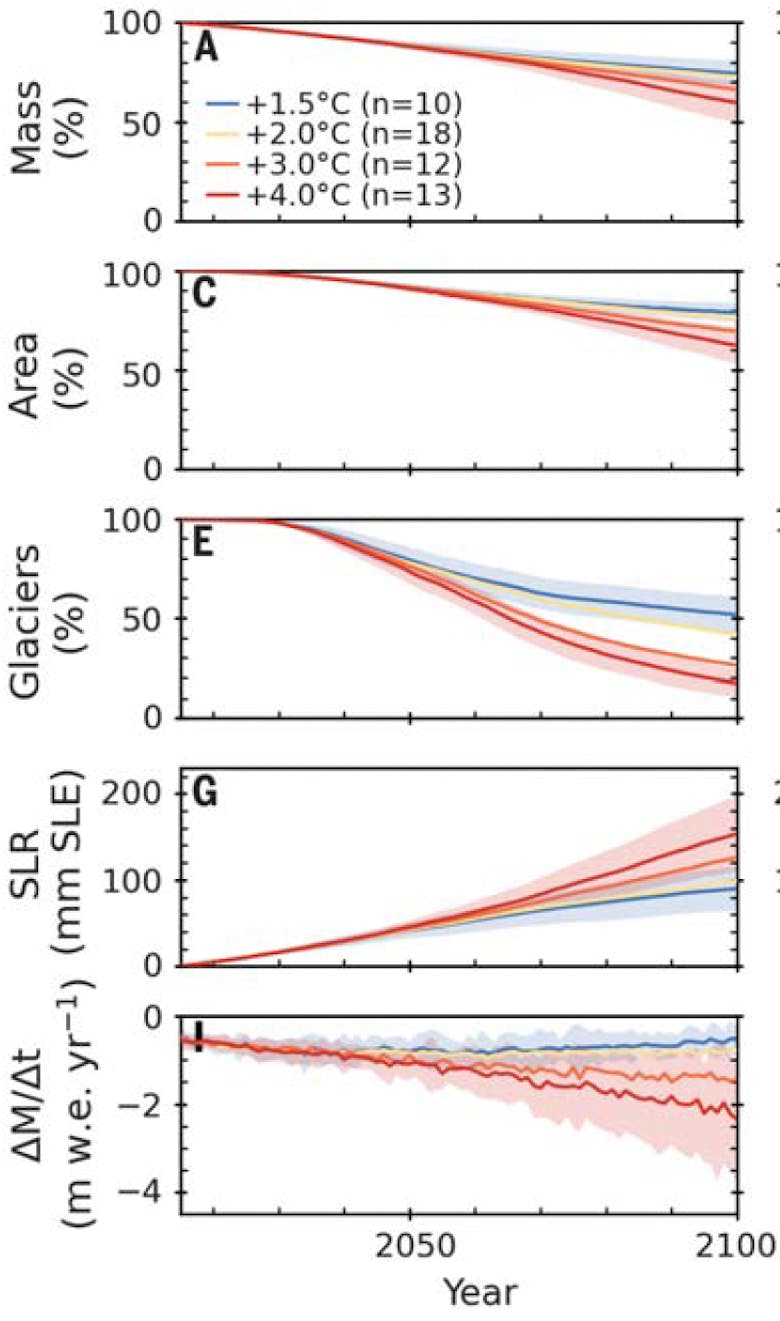

The charts below, from the study, illustrate projected change to (from top to bottom) total glacier mass, area, the number of glaciers remaining ( per cent), sea level rise from glacier melt (in mm of sea level rise equivalent) and area-averaged mass change rate from 2015 to 2100, under a range of temperature scenarios (illustrated with coloured lines).

These temperature scenarios are derived from “shared socioeconomic pathways” for how global society, demographics and economics might change later this century. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer on SSPs.) The projections are grouped based on average global temperature increases by the end of the 21st century, compared with pre-industrial levels.

Projected change to (from top to bottom) total glacier mass, area, the number of glaciers remaining ( per cent), sea level rise from glacier melt (in mm of sea level rise equivalent) and area-averaged mass change rate from 2015 to 2100, under a range of temperature scenarios (illustrated with coloured lines). Credit: Rounce et al. (2022)

The chart illustrates how the percentage of the world’s glaciers remaining on Earth is likely to decline rapidly this century under any temperature scenario, but is expected to become far more severe by the second half of the century under 3-4C of warming when compared to 1.5-2C.

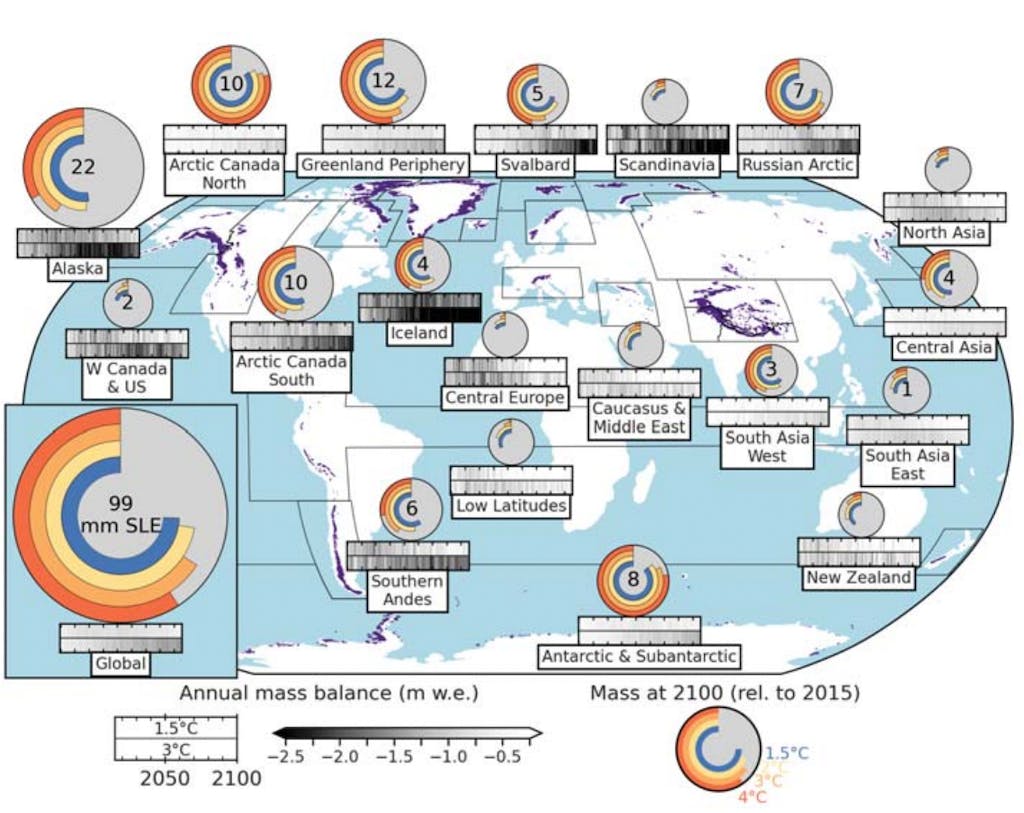

The map below, also taken from the study, illustrates which glacier regions will experience the highest amounts of mass loss and contribute the most to sea level rise from 2015 to 2100.

On the map, discs illustrate mass loss at 2100 under various temperature scenarios (1.5C-4C), while the number represents the glacier’s contribution to sea level rise (in mm) under a 2C scenario.

Mass loss in 2100 under 1.5C-4C (shown in discs) and contribution to sea level rise under 2C (in numbers) for glacier regions across the world. Credit: Rounce et al. (2022)

The map illustrates that Alaska will be the single-largest contributor to global sea level rise from glaciers by the end of the century.

Collectively, Alaska, the Greenland Periphery, Antarctica and north and south Arctic Canada will account for 60-65 per cent of sea level rise from glaciers by 2100, the study adds.

The research notes that, in the High Mountains of Asia – a region supplying water to at least 800 million people, the timing of maximum glacier mass loss is likely to vary, peaking in south-east Asia around 2025-30, central Asia around 2035-55 and south-west Asia around 2050-75.

‘Sobering’

The projections for glacier melt and resultant sea level rise this century are considerably higher than previous estimates, the authors note.

For example, they note that their projections for glacier mass loss under low- and high-emission scenarios are 4-8 per cent greater than previous estimates.

Rounce tells Carbon Brief that this is likely due to several factors, including the team making use of a 2021 study that detailed the acceleration in glacier mass loss observed globally over the last two decades.

This study provided high-resolution data on how every glacier in the world is already being affected by climate change, Rounce explains:

“By calibrating our model with this data, we have a much more complete and detailed picture of the present-day glacier mass change compared to previous models that used regional data or in-situ measurements from a limited number of glaciers.”

In addition, the models used by the team also considered many small-scale physical processes that can worsen or slow the rate of glacier ice loss.

This includes, for example, the presence of debris on top of glaciers, which the research found can lessen glacier mass loss in the short term in some cases, but has little effect overall by 2100.

In a comment piece accompanying the new research, Prof Guðfinna Aðalgeirsdóttir, a researcher at the University of Iceland and Dr Timothy James, a researcher at Queen’s University in Canada, commend the level of detail included in the study. They write:

“By providing model results in the context of policy-relevant end-of-century mean global temperature increases, the authors directly attribute regional mass loss, sea level contributions, and the number of lost glaciers to the consequences of meeting and failing to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-2C temperature limit, and they tell a tragic tale.”

Prof Jonathan Bamber, a leading glaciologist at the University of Bristol who was not involved in the research, also noted the advancements in the methods used by the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

“This is the most comprehensive and rigorous analysis of future glacier trends to date.

“There are some sobering statistics, such as half of all glaciers will have disappeared by 2100 even at 1.5C. Based on current national climate pledges, the situation will be a lot worse with serious implications for communities that rely on glacial runoff for water resources.”

‘Mountain people without mountains’

As well as impacting water supplies, the loss of glaciers will also have profound existential impacts for Indigenous communities living in mountainous areas, says Prof Elizabeth Allison, chair of ecology, spirituality and religion at the California Institute of Integral Studies, who was also not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Throughout the world, glaciated mountains are sacred to people living nearby. [The findings] suggest that communities in mountain regions will undergo profound and unprecedented social, cultural and spiritual change as mountain-dwelling gods and their blessings are perceived to depart from these icy domains.

“When the locus around which societies are oriented disappears, individual and collective psychological disruption and societal breakdown often follows. Adaptation and mitigation planning must include responses to address such psycho-social disruptions.”

The loss of cultural and religious identity from climate change is one aspect of “loss and damage” – a term used to describe how warming is already having an impact on communities around the world, particularly the most vulnerable.

Calls for developed countries to pay for loss and damage from climate change dominated discussions at the last UN climate summit COP27, held in Egypt in 2022. (Read Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer on loss and damage.)

Dr Pasang Sherpa, an Indigenous anthropologist from Pharak in the Nepalese Himalayas based at the University of British Columbia, adds that the new research “has found what [Indigenous people] have long feared”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Significant loss of glaciers means that we are not only witnessing a change in landscape or a loss of natural resources, it means that we are actively complicit in robbing the future from our children. What are mountain peoples without the mountains as we know them?”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.