Shoppers here can buy Fair Trade coffee, organic chocolate and Singapore Green Label notebooks. But they will struggle to find such labels for sustainable palm oil.

Sumatran palm oil plantations clearing land by burning are being blamed for last month’s haze, the worst ever recorded in Singapore.

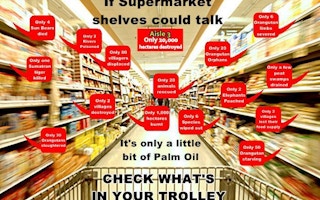

Many people have suggested consumers put pressure on the industry to become more transparent.

Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Vivian Balakrishnan said during the crisis: “I am sure consumers will know what to do.”

Sustainably grown and independently certified palm oil is available. About 16 per cent of the world’s palm oil is certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO - a global association of industry and non-government organisations. But the products here bearing the RSPO trademark, meaning they are made with palm oil produced in an eco-friendly way, consists of just a handful of Body Shop soaps.

Complex supply chains and low palm oil prices mean few manufacturers use only certified palm oil. Often times, firms which commit to buy this will mix it with non-certified oil, so they do not have to build separate processing plants - that way, they can still hit their certified targets.

Alternatively, they buy GreenPalm certificates to show they support the sustainable version. Growers get a certificate for each tonne of sustainable palm oil produced. Buyers in distant countries can purchase these certificates to offset physical sustainable oil if there is none readily available.

To be certified sustainable, mills and growers must meet a set of criteria that include no burning except in limited circumstances, transparency, maintaining customary land use and labour rights and plans for improvement.

The process can be completed in three months but depends on the site’s size and amount of oil produced, said a spokesman for BSI, an independent certification firm. The certification lasts five years, subject to annual audits.

“The additional cost is about $5 per tonne of certified palm oil,” said a spokesman for Singapore-based Golden Agri-Resources, which aims to certify all its pre-June 2010 plantations by 2015. Last week, palm oil prices were hovering around RM2,300 (S$914) a tonne.

If chocolate and soap makers want to use only certified oil for RSPO-trademarked products, they must process them separately from ordinary palm oil, which adds to costs, said World Wide Fund for Nature palm oil spokesman Adam Harrison.

Even so, that does not stop manufacturers from buying and using certified palm oil; just that the end products will not be labelled as such.

Unilever aims to buy all its palm oil from certified suppliers by 2015, while agribusiness giant Cargill has a 2015 target for Europe and 2020 globally.

“Other manufacturers and in particular traders including some of the Singapore-based giants like Wilmar need to show the same level of responsibility,” said Mr Harrison. Some of Wilmar’s suppliers were caught clearing land by setting illegal fires.

But, he added, India and China each buys as much palm oil as Europe and the US combined. So the WWF and RSPO, of which the former is a member, are trying to recruit makers and retailers.

Palm oil may be listed in ingredients as “vegetable oil” so consumers have a hard time telling if a product contains it or is sustainable. But the European Union is set to label all products containing it by late next year.

Another worry, said agribusiness analyst Khor Yu Leng, is that small growers - of the sort caught setting fires illegally in Sumatra - face cost and operating constraints, so getting them certified to high standards is costly. “The next stage is, there needs to be more inclusiveness.”

This week, officials from Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia are discussing the haze at a three-day Asean meeting in Kuala Lumpur.

But consumers still have a role to play. “It’s the processed and packaged foods that drive the increase in oil and fat consumption,” Ms Khor said. “If nobody wants to change their behaviour, their consumption habits, it’s not very realistic.”