Rising temperatures are causing glaciers that harbour 600 billion tonnes of ice in the Himalayas to melt more quickly in recent years, and scientists warn that this will lead to water shortages for 800 million people in future.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Accelerated melting may increase the flow of water during warm seasons to communities downstream in the short term, potentially causing destruction and deadly floods. But scientists behind a new study expect this to taper off “within decades” as glaciers shrink, potentially threatening water supplies.

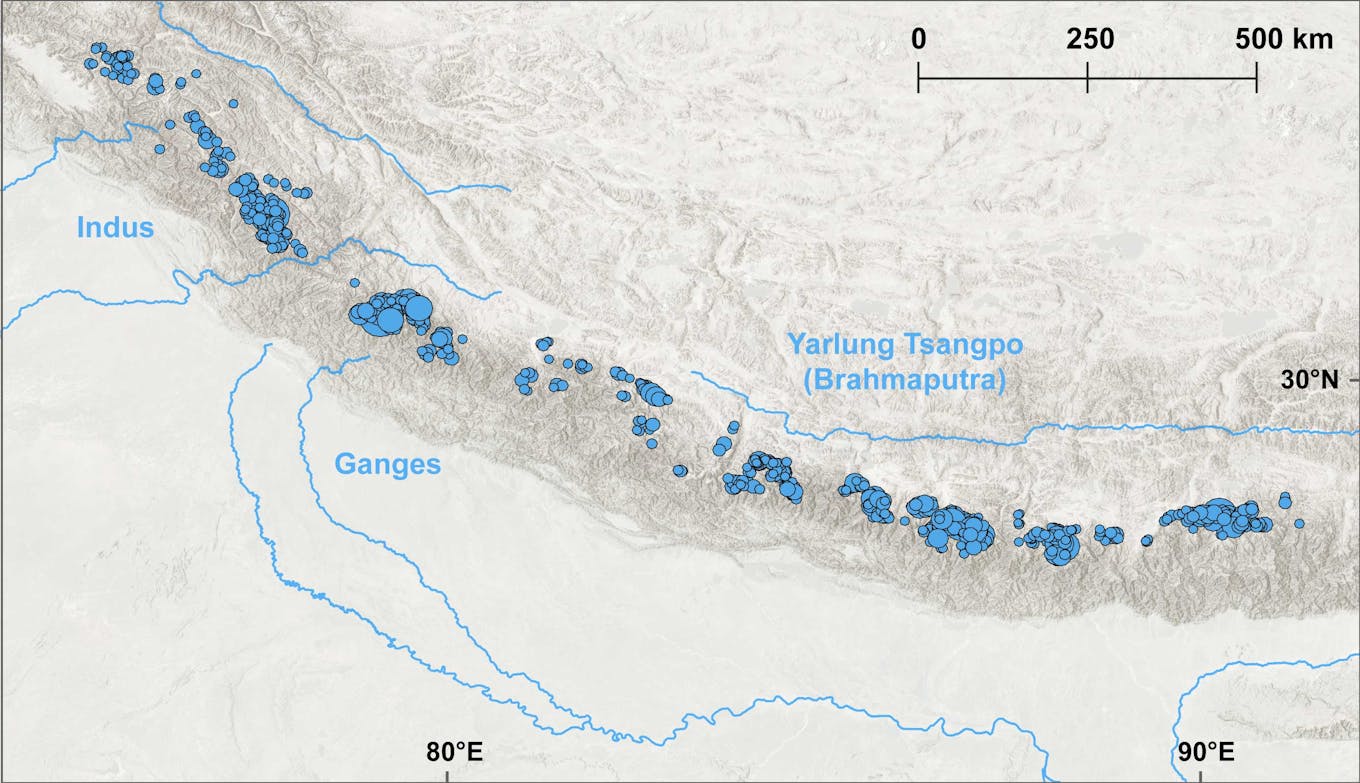

The study analysed satellite images taken over 40 years of some 650 glaciers spanning 2,000km in the Himalayas.

The researchers, led by PhD candidate Joshua Maurer of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, found that the glaciers lost an average of about 0.25m of ice each year between 1975 and 2000.

From 2000, however, the loss increased to about 0.5m a year following a more pronounced warming trend from the 1990s. The average amount lost in recent years has been about eight billion tonnes — the equivalent of 3.2 million Olympic-size swimming pools, said Maurer.

Temperatures from 2000 to 2016 were on average 1°C higher than in 1975 to 2000.

Overview of research sites in Himalayan range, where the each blue circle represents a glacier analysed in the study, over a 40-year period. Image: Joshua Maurer.

Most glaciers are not melting uniformly, and melting has been concentrated mainly at lower elevations where some surfaces are losing as much as five metres a year.

The study shows that “even glaciers in the highest mountains of the world are responding to global air temperature increases driven by the combustion of fossil fuels,” said Joseph Shea, a glacial geographer at the University of Northern British Columbia.

“In the long term, this will lead to changes in the timing and magnitude of streamflow in a heavily populated region,” said Shea.

Temperature the overarching force

The Himalayas, which include Mount Everest, run across Bhutan, China, India, Nepal and Pakistan. Runoff from the glaciers is a source of life to 800 million people, who depend on it for crop irrigation, hydropower and drinking water.

Some researchers have argued that factors other than temperatures are affecting the glaciers. Changes in precipitation and airborne soot from the burning of biomass and fossil fuels are indeed factors, but their effects are highly variable given the huge size and extreme landscapes of the area, said the authors of the latest study, titled Acceleration of ice loss across the Himalayas over the last 40 years, published this week in the journal Science Advances.

Temperature is the overarching force, said Maurer, whose co-authors are Joerg Schaefer and Alison Corley of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Summer Rupper of the University of Utah.

According to news reports, in the high-altitude Spiti Valley in northern India, some 12,000 villagers are already facing water shortages and crop losses due to changes in river flow patterns.

The latest study follows a separate one published in May that estimated yearly runoff is 1.6 times the rate at which the glaciers are replenishing.

Another report on the entire Hindu Kush-Himalayan region also projected the disappearance of one-third of the area’s glaciers by 2100, under the best-case scenario of 1.5°C warming by the end of the century.

Beyond ‘threshold of human survivability’

Just last month, a paper released by an Australian policy institute warned of “existential threat to human civilisation” in the near to medium term, should the planet heat up by 3°C by 2100.

“Climate-change impacts on food and water systems, declining crop yields and rising food prices driven by drought, wildfire and harvest failures have already become catalysts for social breakdown and conflict across the Middle East, the Maghreb and the Sahel [in Africa], contributing to the European migration crisis,” stated the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration in its policy paper.

In its 2050 scenario, more than half of the world’s population (55 per cent) would be subject to more than 20 days a year of lethal heat conditions, “beyond the threshold of human survivability”.

Ecosystems such as coral reef systems, the Amazon rainforest and those in the Arctic would collapse. Water supplies for two billion people living in the dry tropics and subtropics would be directly affected.

Crop yields could decline by 20 per cent in 2050, disrupting global food production.

But the institute said the threat to human existence is not inevitable. It called for policymakers to take a new approach to security risk management and prepare for scenarios where extreme outcomes are fairly probable.