By the time the Laos leg of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is completed in 2021, thousands of Laotians would have been pushed off their land.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In place of these villages, concrete structures and tunnels are now being built to support the 414-kilometre high-speed rail connecting capital Vientiane to the China-Laos border.

Researcher and development practitioner Chawapich Vaidhayakarn from Chiang Mai University said that since the rail project first broke ground in 2016, an estimated 4,400 households have been displaced in Northern Laos.

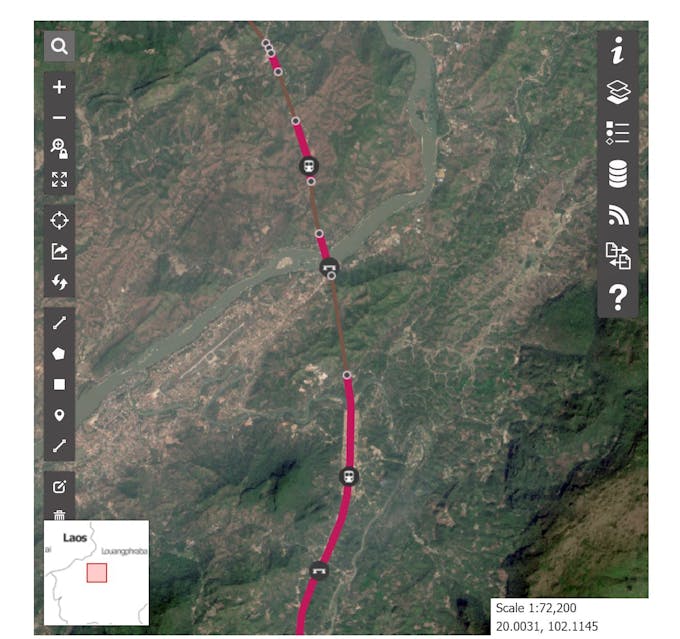

Map showing the China-Laos fast railroad system construction site. Click to enlarge: Design for Conservation

The Lao government promised 5 billion Lao kip (US$587,000) in compensation to the displaced, according to a report by private non-profit media Radio Free Asia. Although the government has said construction would create 7,122 jobs for Laotians, only 3,000 locals had been hired as of November 2017.

Thai researcher and development worker Chawapich Vaidhayakarn, second from front, brings young students to a community forest one hour from Chiang Mai to test water quality from a dam. Image: Chawapich Vaidhayakarn.

This is just one of many similar projects spanning 65 countries from Asia to Europe under President Xi Jin Ping’s massive foreign infrastructure development policy. While China is playing the leading role, it’s clear to see from the case in Laos that it is locals and the environment who are footing the bill for the Asian nation’s ambition.

William Laurance, a scientist from James Cook University in Australia, told Eco-Business that the BRI is an “extraordinarily dangerous” project. “President Xi Jin Ping uses words such as green, sustainable and low-carbon to describe the BRI. I would argue that all those terms are grossly inaccurate.”

China is investing heavily in coal along the BRI countries such as Indonesia, Pakistan and Africa despite its own considerable clean energy investments at home. In Laos and the Greater Mekong region, it is building big hydropower projects that gut intact ecosystems in frontier areas “like a flayed fish”, said Laurance.

“

President Xi Jin Ping uses words such as green, sustainable and low-carbon to describe the BRI. I would argue that all those terms are grossly inaccurate.

William Laurance, researcher, James Cook University

While Laurance acknowledges there is a legitimate need for infrastructure and development in emerging economies, he said there should be a focus on promoting strategic and environmentally sound investments along the BRI. To achieve this, he highlighted the need for four sectors in the host countries to work together: government, media, the scientific community, and civil society.

1. Host nations must step up

Despite its far-reaching social, economic and environmental impact, there is no international body to govern China’s BRI, and to ensure that the country fulfils its green promises.

Because of this, Laurance said that it is crucial for host countries to safeguard their national interest by increasing transparency surrounding the BRI projects.

“What we need is a government that can be transparent and can enforce social and environmental regulations. There are international standards set up for this compliance, but very few Chinese corporations are even members of these, such as The Equator Principles,” he said, referring to a risk management framework for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in project finance.

Laurance said that host countries need to be able to hit the brakes on the BRI projects to have more time to review their impact, such as how Malaysia’s new prime minister Mahathir Mohamed temporarily shelved development plans for a port and a high-speed rail project connecting to Singapore to first review the Southeast Asian country’s escalating debts to China.

2. The scientific community must get involved

Laurance said that scientists must look at the BRI more closely and raise awareness about its impact. For instance, he and his team at the Centre for Tropical Environment and Sustainability Science and the Alliance of Leading Environmental Researchers and Thinkers have engaged with ministers in various countries in Asia, South America and Africa to encourage them to ensure large-scale infrastructure investments are strategic, beneficial to the community, and environmentally sustainable.

Laurance is one of 25 scientists who co-wrote an open letter to Indonesian President Joko Widodo in July to express concerns over the China-funded hydroelectric dam in Batang Toru, North Sumatra, which threatens to fragment the only known habitat of the Tapanuli orangutan, the earth’s most endangered great ape. He wrote another letter in August, warning the president that the dam, “would distract from, rather than enhance, the strong emphasis on the need for wise infrastructure investment and development in Indonesia.”

“Not enough scientists are getting involved at the level of individual projects which is where the threat is really happening,” he said to Eco-Business.

3. A free media

To create a critical mass and put pressure on China to deliver on the BRI’s promised prosperity, the media should continue publishing stories about it, said Laurance. He said Chinese state media foster “institutional brainwashing” by publishing only what’s good about the BRI and cracking down on critics. “People in China only hear the positive. They don’t hear both sides of the issue,” he said.

Laurance cited the 2018 World Press Freedom Index, which ranked China 176th out of 180 countries for free press. “People who want to know about the BRI have to work very hard to do it, and they could be breaking the law,” he said.

4. An active civil society

Civil society must join in to put pressure on governments to ensure that the BRI benefits the people and the environment. “Scientists publishing in journals cannot broaden their influence. Civil society can help by reaching a broader audience, the government, the business and finance sectors that we need to be talking to about these projects,” he said.

Professor William F. Laurance from Australia’s James Cook University briefs the staff of Indonesian President Joko Widodo on the environmental impacts of infrastructure projects, at the Royal Palace in 2016. Image: William F. Laurance