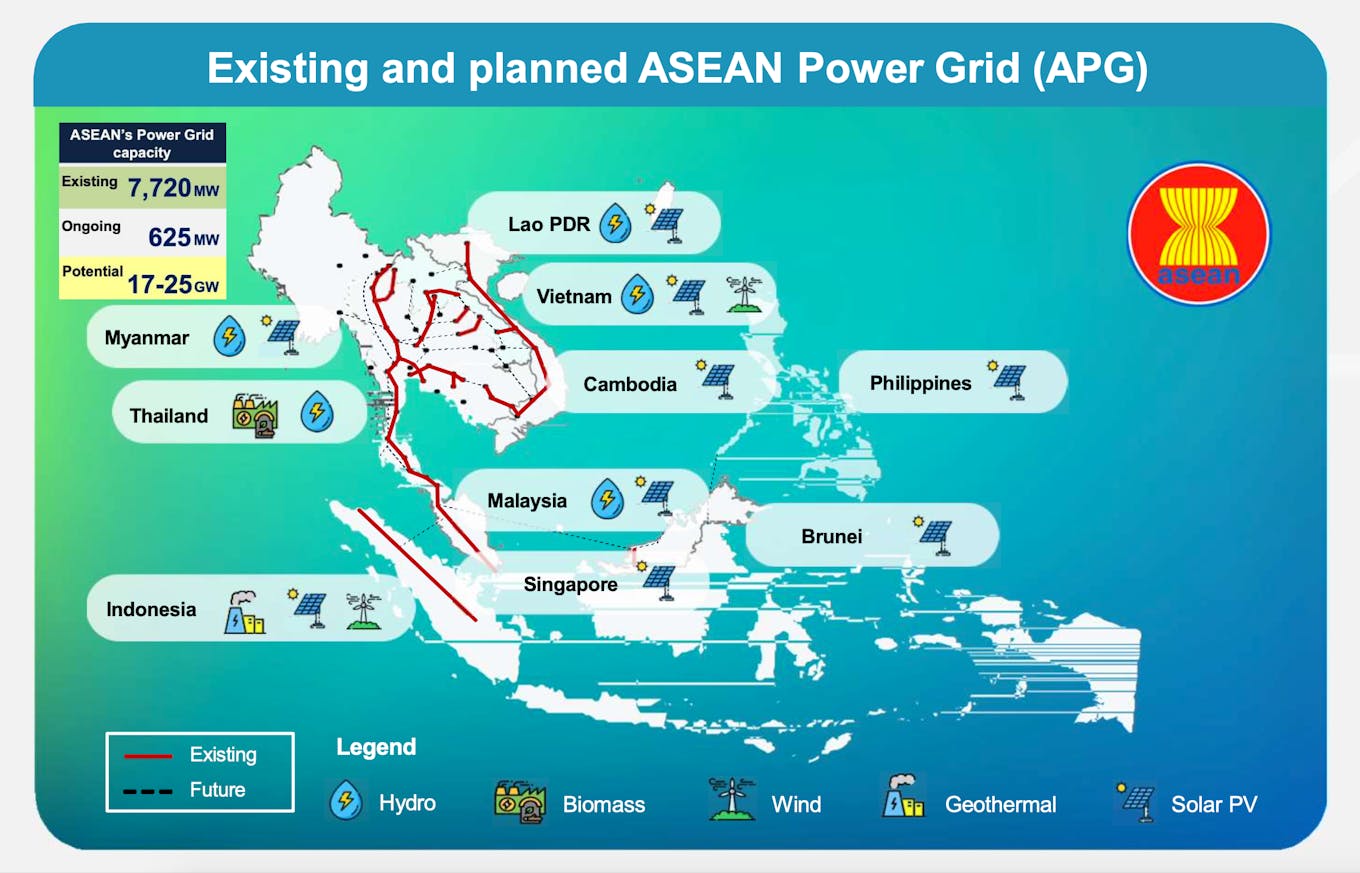

The Asean Power Grid (APG) has long been touted as a key solution to improving the region’s access to secure and affordable energy. Today, the growing urgency to decarbonise the energy sector has made it even more critical for Southeast Asian countries to establish a flexible and reliable cross-border grid, which would improve access to renewable energy resources.

Despite efforts since the 1990s to develop and maintain interconnections across national electricity grids via the APG, the region’s energy demand is expected to triple by 2050 from its 2020 level, according to the 7th Asean Energy Outlook, a 2022 report by the Asean Centre for Energy. Asean will need stronger policies to encourage renewable energy development in line with the regional renewables target of 23 per cent of the total primary energy supply by 2025, the outlook report notes.

Strategic investments will also be crucial to the Asean energy transition. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), up to US$7.3 trillion in investments will be needed to help Asean achieve 100 per cent renewable power generation by 2050.

At Tenaga Nasional Berhad’s (TNB’s) Energy Transition Conference, which took place on 28 and 29 August 2023, speakers discussed the key components needed to achieve a flexible and responsive power grid that can support the scaling up of renewable energy in the region.

Better interconnections

Interconnectors are physical structures that enable high-voltage electricity to flow from one country to another. Crucially, interconnections can match the supply of renewable energy in resource-rich areas to demand centres in neighbouring countries, said the deputy chief executive in the sustainable supply division of Singapore’s Energy Market Authority, Ralph Foong. “These help accelerate the collective decarbonisation of Asean.”

Indonesia, for example, is rich in hydropower and geothermal energy sources, but these areas are often far away from energy demand, said the director of transmission and system planning at state-owned utility PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), Evy Haryadi. The country may also leverage different peak demand times across borders, he added, to optimise the use of interconnectors.

Southeast Asian countries have the potential to share as much as 25 gigawatts of electricity via the Asean Power Grid. Image: 2QFY23 Analyst Briefing, Tenaga Nasional Berhad

In Peninsular Malaysia, TNB is already operating interconnections with neighbouring Thailand and Singapore, highlighted the company’s chief grid officer, Dev Anandan. TNB has recently completed a joint feasibility study with Thailand to upgrade and enhance its cross-border interconnectors to cope with the increased electricity demand from the region’s influx of data centres.

“The interconnections were initially for security, stability and resilience. However, after having signed on to the Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore (LTMS) power exchange, [we are also seeing] hundreds of megawatts in commercial trading potential,” said Anandan.

Embedding digital solutions

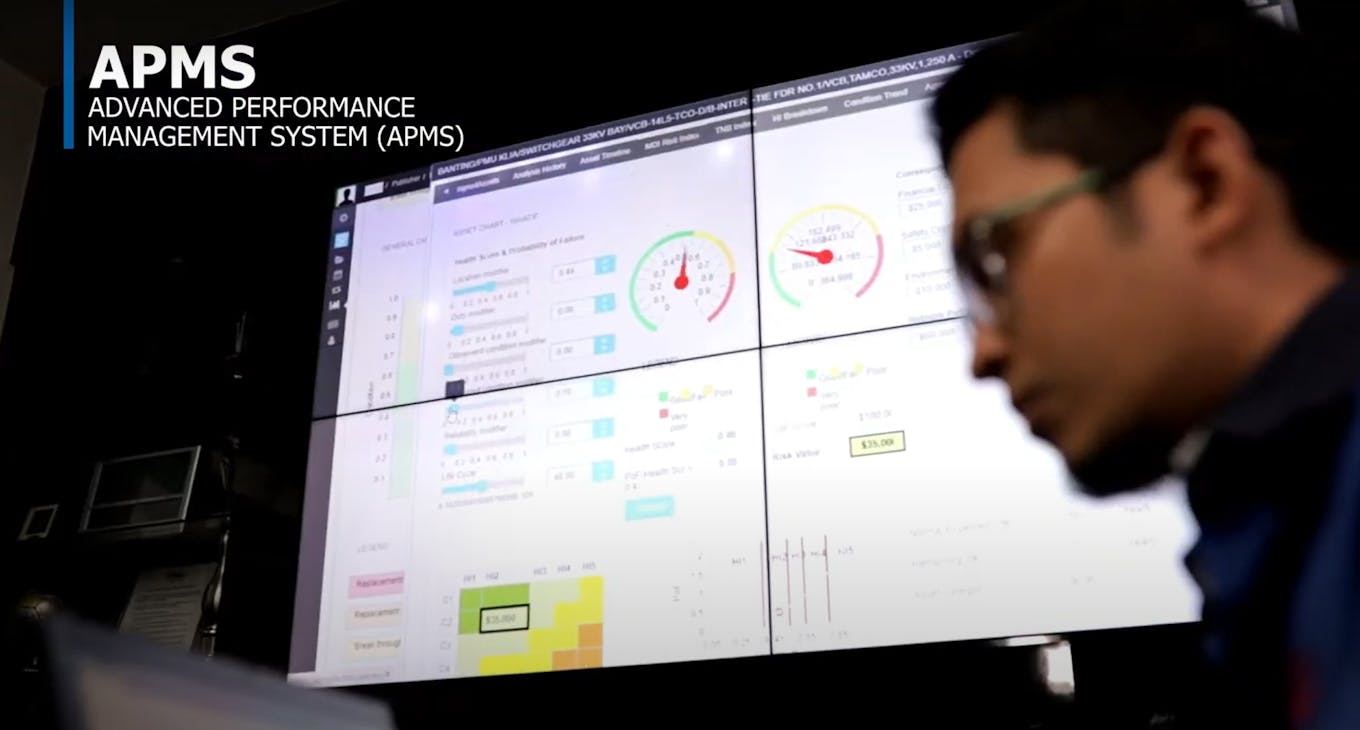

Given the expected increase in grid infrastructure, more sources of information must be analysed concurrently to manage the flow of electricity across Asean. Digitalisation will be crucial in managing data from sources such as weather forecasts, pricing signals and industrial control systems, said Rene Kerkmeester, global vice president for smart grids at tech consultancy CapGemini.

“Only with digital [solutions] are we able to cope with the physical challenges coming our way,” said the chief innovation officer in the electric power digitalisation business unit of Huawei Enterprise Business Group, Edwin Diender.

The main challenge involves “transforming the traditional power grid not into a smart grid, but via the smart grid by adding an intelligent layer of connectivity,” Diender said.

Expanding on Diender’s point, DNV’s director of power grids for Asia Pacific Matthew Rowe recommended that about 15 per cent of investments in grid infrastructure be used to improve digitalisation. This sum should cover the installation of more sensor arrays, the management and monitoring of distribution networks, and advanced analytics capabilities.

More digitised grids could help reduce operational and maintenance costs, increase plant efficiency and forecast hotspots of energy demand, saving operators up to US$80 billion a year, he said, citing an International Energy Agency (IEA) finding.

Operators should also transition from reactive asset management to more predictive practices, Rowe added, referring to using collected data to provide early warnings to maintain grids.

At Tenaga Nasional Berhad, advanced performance management systems use digital software to integrate its numerous utility systems. The system optimises distributed grid performance. Image: TNB

Unlocking finance

Early investments are crucial to improving the regional grid, as a decentralised and flexible power system is key to lowering renewable energy development costs, according to IRENA director-general Francesco La Camera.

While one possible model for financing grid improvements involves treating cross-border transmission as a “regulated asset with a regulated return,” some renewable energy developers are focused on the potential long-term commercial returns from well-structured projects, said Foong of Singapore’s Energy Market Authority.

“What [the developers] ask of other stakeholders at the state and federal levels are for regulatory clarity and certainty to plan,” said Foong.

Being able to reference fixed policy frameworks will also help multilateral development banks fund energy-related developments through concessionary or hybrid finance, he said. “[Blended finance] will serve to enlarge the sweet spot within which various stakeholders can identify and achieve win-win outcomes,” Foong added.

Storing renewable energy

Due to the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources, battery energy storage systems (BESS) are essential for capturing most solar and wind energy when supply peaks, which can be distributed to consumers at peak demand hours.

Flexible energy storage systems can also respond quickly to unexpected increases in energy demand, adding “a huge amount of value to energy systems that cannot be added through conventional generation,” said Rowe.

High battery costs, however, have so far proven challenging for renewable energy developers in Malaysia, said the managing director of Malaysian solar firm Gading Kencana, Dr Muhamad Guntor Mansor Tobeng. Installing BESS is not mandatory for producers under current national schemes to encourage clean energy adoption, such as the Corporate Green Power Programme.

Climate-induced extreme weather has also affected how much renewable energy can be generated, added Guntor. For example, the generation of solar energy in Malaysia has been unpredictable across different months this year. “These erratic weather conditions can affect the efficiency and lifespan of the battery,” he said, noting that the lifecycle of BESS would be harder to calculate.

To overcome these challenges, Malaysia can draw on lessons from countries like Australia, where large-scale battery companies exploit arbitrage – or opt to purchase energy during off-peak hours – in the energy market to generate revenue, said the head of business assessment and engineering at TNB Renewables (TRe), Dr Wan Syakirah Wan Abdullah. Early financing for the first few BESS projects is supported by the Australian government, she noted, in exchange for knowledge from developers of the storage systems.

Malaysia can consider two other models to further implement BESS, said Syakirah. “Option one is to include BESS in the regulated assets or business of TNB, where the company provides all the grid infrastructure,” she said. Option two, she added, would be to open battery supply and management to the market, so makers of independent batteries can support the system.

Due to the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources, battery energy storage systems (BESS) are essential for capturing most solar and wind energy when supply peaks, which can be distributed to consumers at peak demand hours.

An aerial view of battery energy storage systems (BESS) in Malaysia. Image: TNB

Regulatory alignment

Alignment on national policies, especially those surrounding the import and export of renewable energy, will underpin the success of cross-border electricity trade, the speakers agreed. Different grid codes and regulatory prerequisites for energy trade were among the early challenges seen during the development of the APG, said PT PLN’s Haryadi.

“Now the additional challenge is that every country has their decarbonisation targets based on their Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. How can we export renewable energy while also achieving this target?” asked Haryadi. In addressing this, regulators may need to explore mechanisms to trade carbon credits in exchange for renewable energy, he said.

The multitude of stakeholders involved in discussions concerning power generation and transmission might further complicate regulatory negotiations, said Foong. This includes renewable energy developers, owners of operating systems and downstream consumers of renewable energy, in addition to the state and federal regulators with oversight roles.

To date, efforts to enhance Asean’s grid interconnectivity are actively underway, according to TNB. The Malaysian utility provider is actively engaged in talks with its counterparts in Indonesia, Laos, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam via various bilateral memorandums of understanding (MOUs).

TNB is exploring the feasibility of a new interconnection linking Sumatra in western Indonesia to Peninsular Malaysia with PT PLN and the Asean Centre for Energy. Similarly, TNB and Singapore’s SP Power Assets are exploring a second interconnection facility.

TNB is also exploring opportunities in potential renewable energy generation and investments with utility providers in Laos, Thailand and Vietnam.

“We all agreed that the timing was right to make the Asean Power Grid a reality. It is now a matter of our survival,” said TNB president and chief executive officer Dato’ Seri Ir. Baharin bin Din at the Energy Transition Conference 2023.