Malaysia’s economy has grown steadily over the past few decades. Its gross domestic product has expanded by 10 per cent per annum since 1970s, leading to a remarkably low poverty rate.

But a 2018 study by the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) reveals a high rate of malnutrition despite a supposedly healthy economy. This is seen in poor families living in low cost urban housing where conditions are taking a direct toll on the children who live in them.

“In Malaysia and across Southeast Asia, many people eat the same starch-heavy diets every day, including a lot of white rice. They get enough calories to feel full, but not enough micronutrients to be truly healthy and live to their full potential,” says André Rhoen, Asia Pacific vice-president at nutrition and health firm Royal DSM. “This is a form of malnutrition called hidden hunger, a serious problem that impacts human health and society at large.”

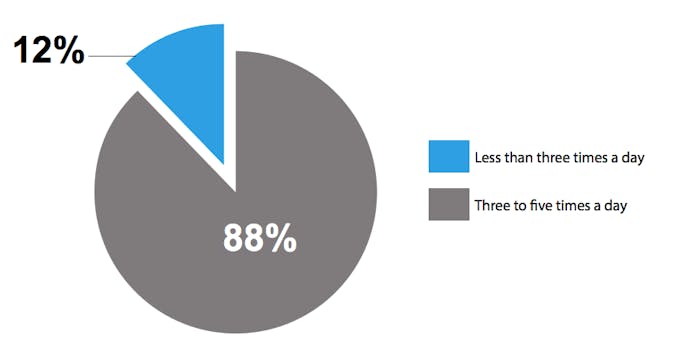

More than 1 in 10 children have less than 3 meals a day. Image: Unicef Malaysia

In an interview with Eco-Business, Rhoen says that malnutrition, or an imbalance in a person’s energy and nutrient intake, is not always obvious, as people who are malnourished can be overweight. Even diets that are poor in nutrients can be rich in calories and lead to obesity.

In Southeast Asia, we need to look at the double burden of malnutrition, when undernutrition and obesity co-exist. Children are often the most vulnerable, he adds. In Malaysia, about 25 per cent of children under age five are either underweight (thinner than average) or stunted (shorter than average) because of poor diets, while about 20 per cent are overweight or obese.

Children who are underweight and stunted are more likely to end up overweight or obese as adults.

“

By fortifying food, like rice for example, people can get better nutrition while eating the same affordable and tasty staple foods without any change to their diets

André Rhoen, Asia Pacific vice-president, human nutrition and health, Royal DSM

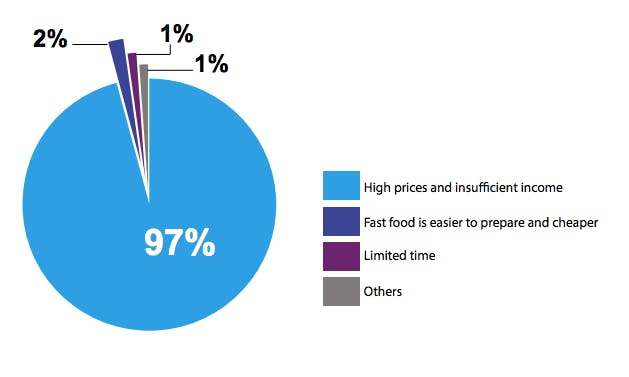

97 per cent of households say that high food prices prevent them from preparing healthy meals for their children. Image: UNICEF Malaysia

Healthy nutrition can be made more affordable for Malaysia’s underprivileged by fortifying their food or increasing its content of essential vitamins and minerals like iron and zinc, says Rhoen.

“By fortifying food, like rice for example, people can get better nutrition while eating the same affordable and tasty staple foods without any change to their diets,” he says.

The average person in Asia eats about 150kg of milled rice every year but its nutritional value is stripped away in the milling process. With fortified rice, people can continue to cook rice in the same way, but people can eat an affordable, filling meal and get the nutrients they need, he adds.

Apart from fortified rice, the Dutch executive suggests using micronutrient powders that come in little packets as another easy, low cost way to supplement everyday diets. The powder can be sprinkled onto regular Malaysian cuisine, like a plate of hokkien noodles, mee goreng or nasi lemak.

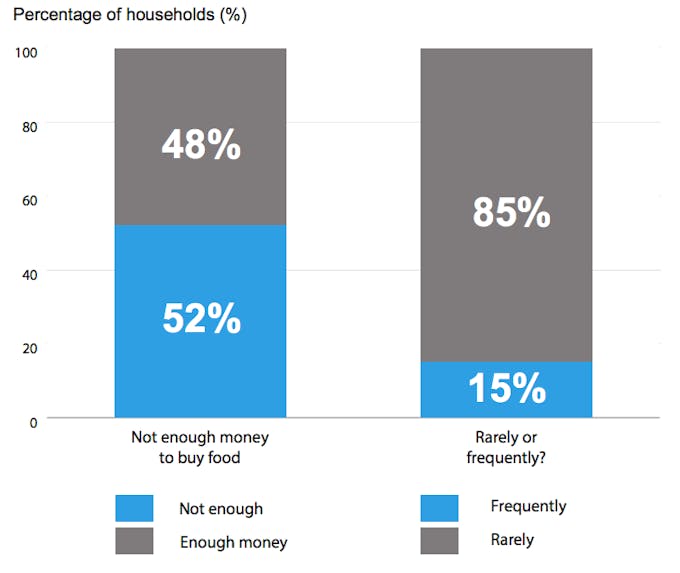

1 in 2 do not have enough money to buy food in recent months and 15 per cent experience this frequently. Image: Unicef Malaysia

Lack of awareness

Rhoen also points to lack of awareness as another driver of Malaysia’s malnutrition problem.

“We need to help people in Malaysia and elsewhere be more aware of the link between nutrition and health, and we need to get more affordable, accessible and nutritious food products to market,” he says.

He calls on policymakers to work together with the private sector, academia and non-government organisations to offer their expertise, resources and knowledge of local diets, including cultural factors to deliver more nutritious food to those who need it most.

Doing its part in spreading awareness, Royal DSM hosted the fourth Sustainable Evidence-based Actions for Change (SEAChange) workshop in Singapore earlier this year, bringing together stakeholders from different sectors to work on scaling-up effective, affordable and nutritious solutions for countries in Asia, including Malaysia.

“We’re already seeing some promising opportunities, and we’re hopeful that these discussions can lead to new partnerships, products and initiatives that will help low-to-middle income consumers across the region get the nutrition they need,” Rhoen says.

Beyond Malaysia

The problem of malnutrition clearly goes well beyond Malaysia, as Southeast Asia is home to about two-thirds of the world’s malnourished children.

There are an estimated 60 million children under the age of five who have stunted growth, a condition that is caused by vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and often goes hand in hand with impaired cognitive development and other serious, sometimes lifelong health issues, including chronic diseases such as obesity and diabetes, he says.

He warns that if left unmanaged, whole economies will bear the consequences where people cannot live up to their full potential, workforce productivity is diminished, and healthcare costs increase. This is why he recommends partnerships across sectors to create and adapt products on a country-by-country basis.

Rhoen adds: “We are working toward solutions across the region but we see the need to treat each country in a unique way.”

DSM is also focusing on India where many people live on less than US$2 a day. Rhoen says giving the country access to fortified rice, micronutrient powders and other affordable nutritious products could have a lifechanging impact for India’s millions of people.

“Sustainability is our core value and we see business as a driver for positive social impact. Our strategy in the region and around the world is aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly zero hunger, good health and wellbeing. We are committed to fighting malnutrition because achieving better health is of global importance and good nutrition is a human right,” he says.