Legal claims made against carbon polluters and greenwashing corporations are rapidly increasing as climate impacts worsen, with climate-vulnerable nations in the Global South accounting for a small but growing proportion of climate lawsuits globally.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Climate-related legal cases have more than doubled globally since 2017, according to new data from Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), as legal challenges are made against climate inaction, fossil fuel extraction, inadequate adaption measures and greenwashing.

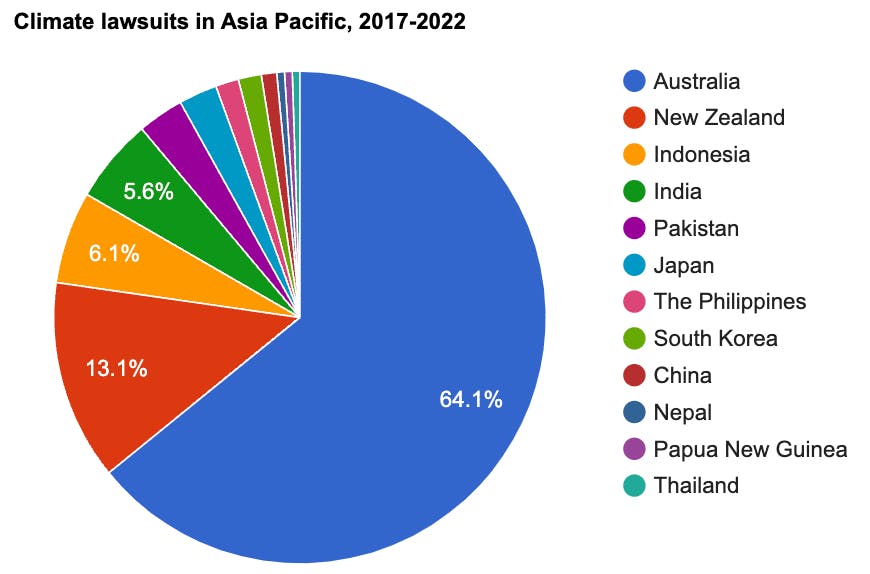

The United States, with its longer history of climate litigation and litigious culture, made about 70 per cent of all climate lawsuits globally (1,522 cases) between 2017 and 2022, according to the study. Australia, where the government was sued for climate inaction by Indigenous groups last year, has seen by far the most cases in Asia Pacific (127 cases).

Climate litigation in Asia Pacific by number of cases, 2017-2022. Data: Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Graphic: Eco-Business

New Zealand (26 cases), Indonesia (12 cases) and India (11 cases) have recorded the highest number of climate-related lawsuits in the region outside of Australia over the past six years. In Indonesia, most cases have been brought against palm oil, mining and logging companies for destroying carbon-rich peatlands. In India, cases were filed by citizens claiming that insufficient climate action has violated their right to a healthy environment.

The region’s most high-profile climate lawsuit was settled in the Philippines last year, where the Commission on Human Rights concluded that 47 major oil and gas firms are liable for climate calamity.

Clearer attribution science

Asia, excluding Oceania, has taken the least climate legal action besides Africa, despite being one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions. Some 5.2 per cent of all climate cases have been filed in developing countries, including small island developing states – although this proportion is growing.

The uptick in climate litigation in the Global South is being driven by non-government organisations, which are pivoting to developing countries as they diversify their climate impact strategies, said Maria Antonia Tigre, senior fellow, global climate change litigation, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, at a panel discussion on the findings.

Limited legal capacity, infrastructure and financial means have slowed climate litigation in the Global South to date, but that is now changing, allowing more cases to be made against carbon polluters in climate-vulnerable regions, noted Andrew Raine, senior legal officer with UNEP.

The study, published on Thursday (27 July), finds that the scope of climate litigation is expanding as the science behind attributing harm to climate change becomes clearer, giving citizens and non-government organisations more ammunition to hold corporations and governments to account.

Raine noted that while there has been “huge growth” in climate litigation globally, there have not been incidences of compensation paid to victims of climate-related harm.

One of the few cases of an individual claiming compensation for climate-related harm is Saúl Luciano Lliuya, a Peruvian farmer who sued German energy company RWE for damage to his home caused by RWE’s emissions. The case, which was filed in 2015, is ongoing.

Future trends in climate litigation will likely see more cases involving the cross-border impacts of climate change, climate migrants, the attribution of damage to climate change and vulnerable groups such as Indigenous peoples, the report noted.

There will also be more backlash against climate activists in courtrooms as governments and corporations push back against moves to block the extraction of fossil fuels or transition minerals, the report predicted.

UNEP’s study launches a year after the UN General Assembly declared that access to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a universal human right.