The UK’s new, long-awaited hydrogen strategy provides more detail on how the government will support the development of a domestic low-carbon hydrogen sector, which today is virtually non-existent.

Experts have warned that, with hydrogen in short supply in the coming years, the UK must prioritise it in “hard-to-electrify” sectors such as heavy industry as capacity expands.

Meanwhile, firm decisions around the extent of hydrogen use in domestic heating and how to ensure it is produced in a low-carbon way have been delayed or put out to consultation for the time being.

In this article, Carbon Brief highlights key points from the 121-page strategy and examines some of the main talking points around the UK’s hydrogen plans.

Why does the UK need a hydrogen strategy?

Hydrogen is widely seen as a vital component in plans to achieve net-zero emissions and has been the subject of considerable hype, with many nations prioritising it in their post-Covid green recovery plans.

Its versatility means it can be used to tackle emissions in “hard-to-abate” sectors, such as heavy industry, but it currently suffers from high prices and low efficiency.

Critics also characterise hydrogen – most of which is currently made from natural gas – as a way for fossil fuel companies to maintain the status quo. (For all the advantages and disadvantages of hydrogen, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer.)

In its new strategy, the UK government makes it clear that it sees low-carbon hydrogen as a key part of its net-zero plan, and says it wants the nation to be a “global leader on hydrogen” by 2030.

The document contains an exploration of how the UK will expand production and create a market for hydrogen based on domestic supply chains. This contrasts with Germany, which has been looking to import hydrogen from abroad.

Prior to the new strategy, the prime minister’s 10-point plan in November 2020 included plans to produce five gigawatts (GW) of annual low-carbon hydrogen production in the UK by 2030. Currently, this capacity stands at virtually zero.

The plan also called for a £240m net-zero hydrogen fund, the creation of a hydrogen neighbourhood heated with the gas by 2023, and increasing hydrogen blending into gas networks to 20 per cent to reduce reliance on natural gas.

There were also over 100 references to hydrogen throughout the government’s energy white paper, reflecting its potential use in many sectors. It also features in the industrial and transport decarbonisation strategies released earlier this year.

However, as with most of the government’s net-zero strategy documents so far, the hydrogen plan has been delayed by months, resulting in uncertainty around the future of this fledgling industry.

Companies such as Equinor are pressing on with hydrogen developments in the UK, but industry figures have warned that the UK risks being left behind. Other European nations have pledged billions to support low-carbon hydrogen expansion.

In some applications, hydrogen will compete with electrification and carbon capture and storage (CCS) as the best means of decarbonisation.

However, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) has noted that, in order to hit the UK’s carbon budgets and achieve net-zero emissions, decisions in areas such as decarbonising heating and vehicles need to be made in the 2020s to allow time for infrastructure and vehicle stock changes.

Hydrogen growth for the next decade is expected to start slowly, with a government aspiration to “see 1GW production capacity by 2025” laid out in the strategy.

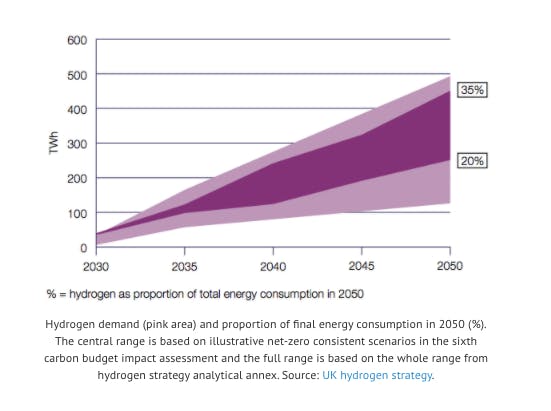

However, as the chart below shows, if the government’s plans come to fruition it could then expand significantly – taking up between 20-35 per cent of the nation’s total energy supply by 2050. This will require a major expansion of infrastructure and skills in the UK.

A recent All Party Parliamentary Group report on the role of hydrogen in powering industry included a list of demands, stating that the government must “expand beyond its existing commitments of 5GW production in the forthcoming hydrogen strategy”. This call has been echoed by some industry groups.

The strategy does not increase this target, although it notes that the government is “aware of a potential pipeline of over 15GW of projects”.

What variety of ‘low-carbon’ hydrogen will be prioritised?

At the heart of many discussions about low-carbon hydrogen production is whether the hydrogen is “green” or “blue”.

Green hydrogen is made using electrolysers powered by renewable electricity, while blue hydrogen is made using natural gas, with the resulting emissions captured and stored.

The former is essentially zero-carbon, but the latter can still result in emissions due to methane leaks from natural gas infrastructure and the fact that carbon capture and storage (CCS) does not capture 100 per cent of emissions.

The new strategy largely avoids using this colour-coding system, but it says the government has committed to a “twin track” approach that will include the production of both varieties.

Supporting a variety of projects will give the UK a “competitive advantage”, according to the government. Germany, by contrast, has said it will focus exclusively on green hydrogen.

The CCC has previously stated that the government should “set out [a] vision for contributions of hydrogen production from different routes to 2035” in its hydrogen strategy.

The document does not do that and instead says it will provide “further detail on our production strategy and twin track approach by early 2022”.

Many scientists and environmental groups are sceptical about blue hydrogen given its associated emissions.

Jess Ralston, an analyst at thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), said in a statement that the government should “be alive to the risk of gas industry lobbying causing it to commit too heavily to blue hydrogen and so keeping the country locked into fossil fuel-based technology”.

This opposition came to a head when a recent study led to headlines stating that blue hydrogen is “worse for the climate than coal”.

However, there was considerable pushback on this conclusion, with other researchers – including CCC head of carbon budgets, David Joffe – pointing out that it relied on very high methane leakage and a short-term measure of global warming potential that emphasised the impact of methane emissions over CO2.

For its part, the CCC has recommended a “blue hydrogen bridge” as a useful tool for achieving net-zero. It says allowing some blue hydrogen will reduce emissions faster in the short-term by replacing more fossil fuels with hydrogen when there is not enough green hydrogen available.

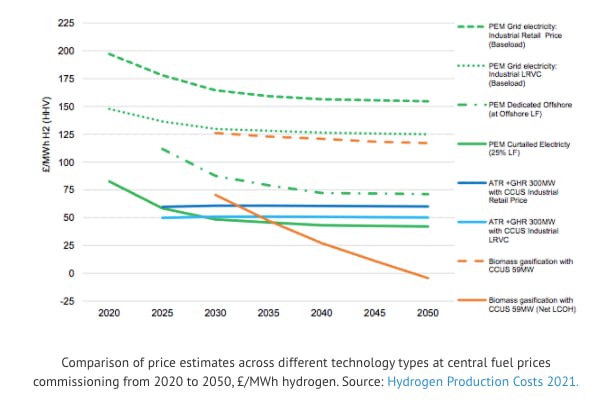

As it stands, blue hydrogen made using steam methane reformation (SMR) is the cheapest low-carbon hydrogen available, according to government analysis included in the strategy. (For more on the relative costs of different hydrogen varieties, see this Carbon Brief explainer.)

The plan notes that, in some cases, hydrogen made using electrolysers “could become cost-competitive with CCUS [carbon capture, utilisation and storage]-enabled methane reformation as early as 2025”.

The chart below, from a document outlining hydrogen costs released alongside the main strategy, shows the expected declining cost of electrolytic hydrogen over time (green lines). (This includes hydrogen made using grid electricity, which is not technically green unless the grid is 100 per cent renewable.)

The strategy states that the proportion of hydrogen supplied by particular technologies “depends on a range of assumptions, which can only be tested through the market’s reaction to the policies set out in this strategy and real, at-scale deployment of hydrogen”.

The CCC has warned that policies must develop both green and blue options, “rather than just whichever is least-cost”.

Prof Robert Gross, director of the UK Energy Research Centre, tells Carbon Brief that, in his view, it is “probably a bit unhelpful to get too preoccupied with the green vs blue hydrogen debate”. He says:

“If we want to demonstrate, trial, begin to commercialise and then roll out the use of hydrogen in industry/air travel/freight or wherever, then we need enough hydrogen. We can’t wait until the supply side deliberations are complete.”

In May, S&P Global Platts reported that Rita Wadey – hydrogen economy deputy director at the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) – said that, rather than “blue” or “green”, the UK would “consider carbon intensity as the primary factor in market development”.

The government has released a consultation on low-carbon hydrogen standards to accompany the strategy, with a pledge to “finalise design elements” of such standards by early 2022.

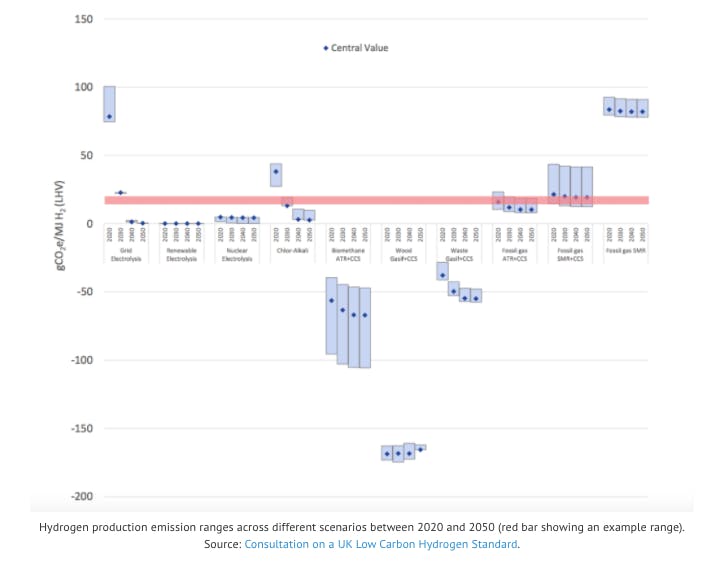

It has also released an accompanying report, prepared by consultancies E4Tech and Ludwig-Bölkow-Systemtechnik (LBST), which examines maximum acceptable levels of emissions for low-carbon hydrogen production and the methodology for calculating these emissions.

The figure below from the consultation, based on this analysis, shows the impact of setting a threshold of 15-20gCO2e per megajoule (MJ) of hydrogen (red bar). In this example, those production methods above the red line, including some for producing blue hydrogen, would be excluded.

In the example chosen for the consultation, natural gas routes where CO2 capture rates are below around 85 per cent were excluded.

The CCC has previously defined “suitable emissions reductions” for blue hydrogen compared to fossil gas as “at least 95 per cent CO2 capture, 85 per cent lifecycle greenhouse gas savings”.

How will hydrogen be used in different sectors of the economy?

Although low-carbon hydrogen can be used to do everything from fuelling cars to heating houses, the reality is that it will likely be limited by the volume that can feasibly be produced.

Some applications, such as industrial heating, may be virtually impossible without a supply of hydrogen, and many experts have argued that these are the cases where it should be prioritised, at least in the short term.

Michael Liebrich of Liebreich Associates has organised the use of low-carbon hydrogen into a “ladder”, with current applications – such as the chemicals industry – given top priority.

The new strategy is clear that industry will be a “lead option” for early hydrogen use, starting in the mid-2020s. It also says that it will “likely” be important for decarbonising transport – particularly heavy goods vehicles, shipping and aviation – and balancing a more renewables-heavy grid.

Commitments made in the new strategy include:

- Call for evidence on “hydrogen-ready” industrial equipment by the end of 2021.

- Call for evidence on phaseout of carbon-intensive hydrogen production in industry “within a year”.

- Phase 2 of the £315m Industrial Energy Transformation Fund.

- A £55 million Industrial Fuel Switching 2 competition in 2021.

One notable exclusion is hydrogen for fuel-cell passenger cars. This is consistent with the government’s focus on electric cars, which many researchers view as more efficient and cost-effective technology.

However, the strategy also includes the option of using hydrogen in sectors that may be better served by electrification, particularly domestic heating, where hydrogen has to compete with electric heat pumps.

It contains plans for hydrogen heating trials and consultation on “hydrogen-ready” boilers by 2026.

Juliet Phillips, senior policy advisor and UK hydrogen expert at thinktank E3G tells Carbon Brief the strategy had “left open” the door for uses that “don’t add the most value for the climate or economy”. She adds:

“Stronger signals of intent could steer private and public investments into those areas which add most value. The government has not clearly laid out how to decide upon which sectors will benefit from the initial planned 5GW of production and has instead largely left this to be determined through trials and pilots.”

Responding to the report, energy researchers pointed to the “miniscule” volumes of hydrogen expected to be produced in the near future and urged the government to choose its priorities carefully.

“As the strategy admits, there won’t be significant quantities of low-carbon hydrogen for some time. [Therefore] we need to use it where there are few alternatives and not as a like-for-like replacement of gas,” Dr Jan Rosenow, director of European programmes at the Regulatory Assistance Project, in a statement.

Government analysis, included in the strategy, suggests potential hydrogen demand of up to 38 terawatt-hours (TWh) by 2030, not including blending it into the gas grid, and rising to 55-165TWh by 2035.

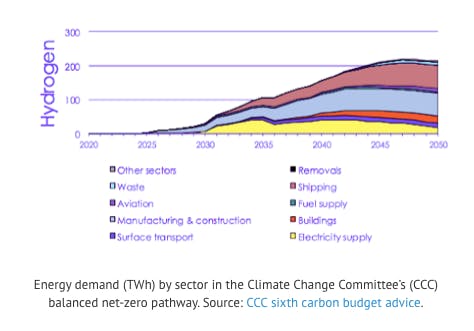

This is in line with the CCC’s recommendation for its net-zero pathway, which sees low-carbon hydrogen scaling up to 90TWh by 2035 – around a third of the size of the current power sector.

The committee emphasises that hydrogen use should be restricted to “areas less suited to electrification, particularly shipping and parts of industry” and providing flexibility to the power system.

The CCC does not see extensive use of hydrogen outside of these limited cases by 2035, as the chart below shows.

The government is more optimistic about the use of hydrogen in domestic heating. Its analysis suggests that up to 45TWh of low-carbon hydrogen could be put to this use by 2035, as the chart below indicates.

However, the starting point for the range – 0TWh – suggests there is considerable uncertainty compared to other sectors, and even the highest estimate is only around a 10th of the energy currently used to heat UK homes.

Coverage of the report and government promotional materials emphasised that the government’s plan would provide enough hydrogen to replace natural gas in around 3m homes each year.

However, in the actual report, the government said that it expected “overall the demand for low carbon hydrogen for heating by 2030 to be relatively low (<1TWh)”.

Much will hinge on the progress of feasibility studies in the coming years, and the government’s upcoming heat and buildings strategy may also provide some clarity.

Finally, in order to create a market for hydrogen, the government says it will examine blending up to 20 per cent hydrogen into the gas network by late 2022 and aim to make a final decision in late 2023.

Gniewomir Flis, a project manager at Agora Energiewende, tells Carbon Brief that – in his view – blending “has no future”. He explains:

“I would suggest to go with these no-regret options for hydrogen demand [in industry] that are already available… those should be the focus.”

How does the government plan to support the hydrogen industry?

As it stands, low-carbon hydrogen remains expensive compared to fossil fuel alternatives, there is uncertainty about the level of future demand and high risks for companies aiming to enter the sector.

The 10-point plan included a pledge to develop a hydrogen business model to encourage private investment and a revenue mechanism to provide funding for the business model.

The new hydrogen strategy confirms that this business model will be finalised in 2022, enabling the first contracts to be allocated from the start of 2023. This is pending another consultation, which has been launched alongside the main strategy.

According to the government’s press release, its preferred model is “built on a similar premise to the offshore wind contracts for difference (CfDs)”, which significantly cut costs of new offshore wind farms.

These contracts are designed to overcome the cost gap between the preferred technology and fossil fuels. Hydrogen producers would be given a payment that bridges this gap.

Much of the resulting press coverage of the hydrogen strategy, from the Financial Times to the Daily Telegraph, focused on the plan for a hydrogen industry “subsidised by taxpayers”, as the money would come from either higher bills or public funds.

However, Anne-Marie Trevelyan – minister for energy, clean growth and climate change at BEIS – told the Times that the cost to provide long-term security to the industry would be “very small” for individual households.

Now that its strategy has been published, the government says it will gather evidence from consultations on its low-carbon hydrogen standard, net-zero hydrogen fund and the business model:

“This will give us a better understanding of the mix of production technologies, how we will meet a ramp-up in demand, and the role that new technologies could play in achieving the levels of production necessary to meet our future [sixth carbon budget] and net-zero commitments.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.