Forest-based carbon projects are increasingly in vogue.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The idea is that companies can negate a certain amount of emissions from their operations by buying up carbon credits from projects that, in general, planted new trees or protected existing ones standing in harm’s way, hence preventing an equivalent amount of emissions that would occur through the loss of forests.

But one particular credit issuance last December, from protecting lush rainforests in Guyana, has caught the attention of the carbon market. For the South American country largely never had issues with excessive tree felling, in contrast to countries like Brazil or Indonesia that face rampant deforestation.

In other words, it was hard to say, based on precedence, that forests in Guyana were in danger of being mowed down. This was the first time carbon credits have been issued in such a scenario.

While hardly anyone is arguing against sending more conservation money to Guyana, an “upper-middle income economy” by the World Bank’s rubrics, the transaction has generated concern that such projects overstate their decarbonisation potential in the way their carbon credits are calculated.

At the same time, major conservation groups and carbon market players are throwing their weight behind such projects, which are expected to grow in the coming years.

High-forest, low-deforestation

Over 85 per cent of Guyana is covered by forests, and according to open-source platform Global Forest Watch, the country lost only 0.36 per cent of tree cover between 2000 and 2020.

These statistics allow the country to fit easily into a group of “high-forest, low-deforestation”, or HFLD jurisdictions, defined as developing states with forest cover of over 50 per cent. This figure is only allowed to fall each year by a small margin of 0.22 per cent. Other countries on the list include Suriname, also in South America, Gabon in Africa, and Bhutan in Asia.

These countries contain nearly a quarter of the world’s remaining forests. Some nations protect their forests well; others have slow economic growth that prevents farms, factories and cities from quickly taking over plots of old growth.

Either way, their green endowment is a curse in today’s carbon markets, which prioritise projects in places where trees have already fallen, or would soon be facing the guillotine. In a 2007 paper, scientists had already said that HFLD countries could face high deforestation in the future if they cannot make money from keeping their trees standing, while other countries with poorer forest management track records can – an argument that is still being surfaced today.

There is also the reasoning that HFLD countries could see accelerated economic growth in the near future, putting their forests at risk and necessitating early interventions.

Additionality issues

Standard setters of carbon projects have in recent years developed methods specific to generating carbon credits in HFLD countries.

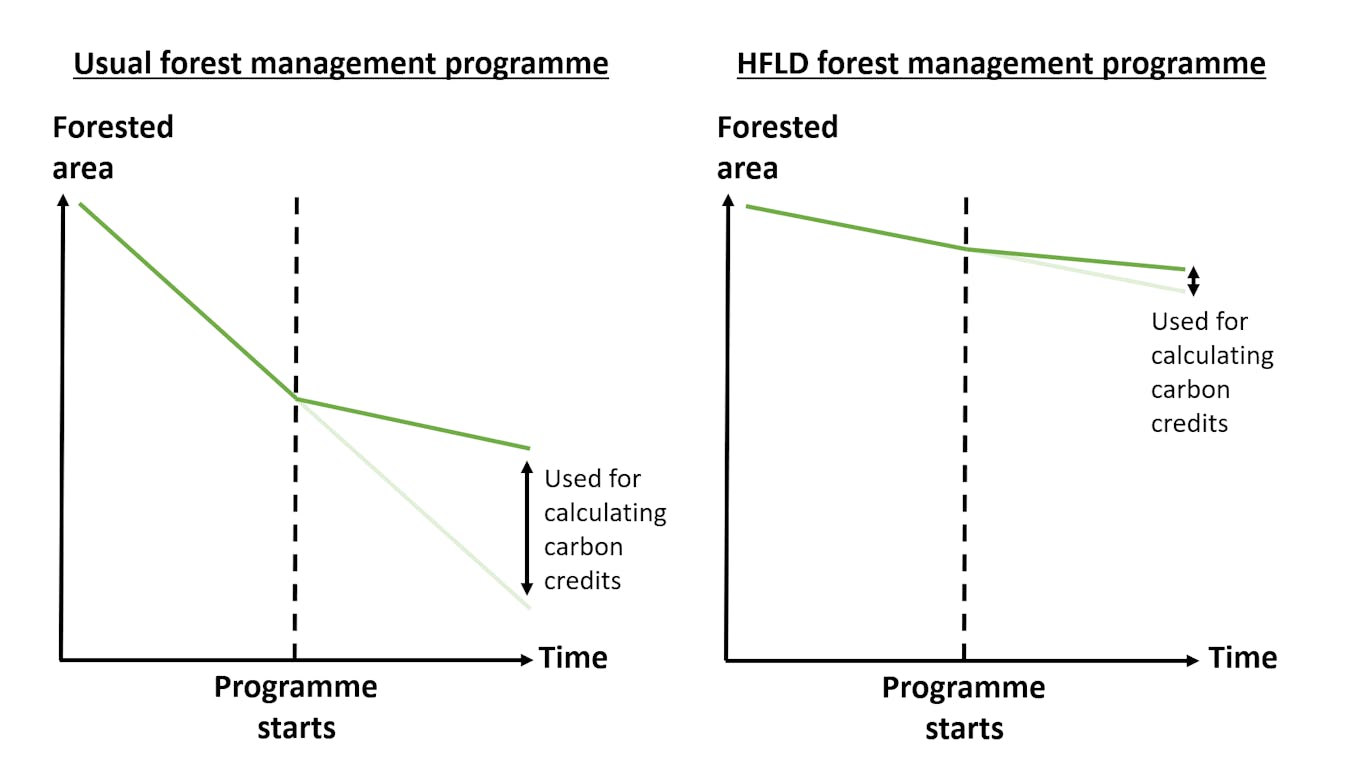

A general representation of deforestation rates over time in normal forest management programmes (left), versus if the programme runs in an HFLD country (right), depicting the low volume of carbon credits in the latter without adjustments. Visual adapted from Sylvera. [Click to enlarge]

They generally allow these nations to bump up the number of carbon credits, tagged to a fraction of their standing forests. The idea is that without such adjustments, very few credits and little revenue can be generated because of the country’s low deforestation rate to start with.

For example, in the case of Guyana, the country was allowed to sell more carbon credits based on an equation that included 0.05 per cent of its forest stock, among other qualifiers like deforestation rate and total forest cover. The rules were developed by United States-based standards organisation Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART).

The adjustment meant that Guyana could issue over 33 million carbon credits, each representing a tonne of carbon dioxide emissions avoided, instead of only about 5 million. American oil and gas firm Hess Corporation has signed a deal that could see it buy a third of the total credits, worth US$750 million, by 2030.

Concerned practitioners have said that this inflation could undermine carbon markets, since companies would be allowed to claim offsets that do not represent any emissions reductions arising from the particular project – contravening a key principle known as ‘additionality’ in carbon offsetting.

ART leadership said its methodology is conservative and ensures that HFLD credits represent additional climate action, given that it requires countries to mitigate forest loss and maintain their low rates of deforestation as part of its programme. Protecting intact, pristine forests in HFLD jurisdictions can be especially beneficial for conservation and climate change, it added.

Other programmes, such as the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, allow HFLD adjustments to rise to 0.1 per cent of the countries’ forests – double that of ART’s rules. Such rules also generally come with safeguards such as setting aside ‘buffer’ credits, reviewing the numbers used every few years, and mandating conformity to community protection guidelines.

“It is a tricky situation,” said Gilles Dufrasne, global carbon markets lead at non-profit Carbon Market Watch, adding that a small percentage change to calculations in HFLD programmes could introduce large quantities of credits “that should not be there”.

There needs to be a “very strong basis” to justify deforestation risks and numbers used in HFLD calculations, Dufrasne added.

“The fact that there are fundamental questions around the additionality of HFLD credits calls into question whether they are really comparable with other credits in the market, and whether they should be eligible for offsetting purposes,” said Polly Thompson, policy associate at United Kingdom-based carbon offsets rating firm Sylvera, in a policy briefing last week.

In the briefing, Sylvera senior policy associate Carmen Alvarez Campo also said that ART may revise its HFLD provisions given the “numerous concerns” that have surfaced.

In response to queries, the ART secretariat told Eco-Business that it does not have immediate plans to revise its current methodology developed in 2021, but that its entire standard will undergo review at least every three years, with the next scheduled for 2024. Proposed revisions will also undergo public consultation, it added.

Verra has said in 2021 it could look into formulating HFLD rules for jurisdictional projects, but its current methodology does not make special exceptions.

Broadening support

Meanwhile, HFLD programmes are receiving increasing support worldwide. Notably, Corsia, a global carbon offsetting programme for airlines, allows the use of such credits issued by ART.

Last November, a group of major stakeholders, including Singapore-based carbon marketplace Climate Impact X and several US-based conservation non-profits, released a report on HFLD credits, arguing that funding for forest preservation should not come only when they are threatened.

Looking ahead, Gabon, the second most forested country worldwide, is also registering a forest carbon programme with ART, and could issue HFLD credits. Last October, Gabon separately verified 90 million carbon credits with a United Nations programme.

The ART secretariat said that it expects to see continued growth of the HFLD sector, though it cannot say when additional credits will be approved.

Correction note: Paragraph 24 has been edited to better reflect Verra’s updates on HFLD rules.