This is part of a wider trend in which companies and governments take advantage of weak or unclear land rights to lease out swathes of communal land in the global south.

Many of these deals involve foreign companies using the land for logging, intensive agriculture, fossil-fuel extraction and mining. Increasingly, firms are also seeking land that they can use to sell carbon offsets.

The research, published in Land Use Policy, identifies around 18m hectares of land in Cambodia, Colombia and the DRC that have been acquired in large-scale deals.

Overall, around 6 per cent of the acquired land overlaps with areas that are either legally recognised as belonging to local and Indigenous communities or, in the case of the DRC, are traditionally managed by Indigenous groups.

‘Vast land resources’

Large swathes of land in the global south have traditionally been managed by local communities and Indigenous people. However, their claims to these areas – their land tenure rights – have long been under threat.

Between the 15th and 20th centuries, European powers seized territory from many Indigenous people across the global south. During decolonisation, many of these “land grabs” were never reversed and much of the formerly communal land passed straight into the hands of newly created countries, particularly in parts of Africa and Asia.

There has been growing recognition of traditional ownership in recent years. Over 2015-20, 103m hectares of communal lands in 73 countries were given legal status, according to analysis by the Rights and Resources Initiative, a global coalition of groups that advocates for the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

This brings the legal recognition of traditional ownership to around 1,265m hectares, or 19 per cent of land in the countries assessed, as of 2020.

“

It cannot be that people who conserve forests for centuries don’t receive anything and investors just come in and make money with these kinds of business models.

Dr Christoph Kubitza, research fellow, German Institute for Global and Area Studies

However, this legal recognition has frequently not stopped companies from entering these regions to harvest or extract a range of commodities, from palm oil and timber to copper and gold. The study authors say communal land is often viewed as an untapped resource, writing:

“The lack of private ownership and intensive production systems probably led to the notion that countries in the global south still harbour vast land resources suitable for commercial production.”

Officials in global-south nations lease out “vast tracts of land” to these companies – many of which are based overseas – without seeking communities’ consent or guaranteeing them benefits, the authors say. These rental agreements can last for several decades.

Study co-author Dr Christoph Kubitza, a research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, says that even in nations where communal lands are legally recognised, such claims are sometimes poorly enforced by central governments. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You have some element in [national] legislation that speaks to communal lands, but implementation just does not work.”

In order to understand the scale of conflict between communal land rights and the transfer of land to companies, Kubitza and his colleagues merged data on the location of “large-scale land acquisitions” from the Land Matrix monitoring initiative with maps of communal land ownership assembled by LandMark and Open Development Cambodia.

(The definition of “large-scale land acquisition” varies, but Land Matrix broadly defines it as an attempt to buy, lease or otherwise acquire an area of land that is 200 hectares or more in size.)

They used data covering the period 2000-22 from Colombia, Cambodia and the DRC – three rainforest nations where governments provide varying levels of protection for communal lands.

‘Alarming’

The researchers identified 18.1m hectares of land that have been targeted for large-scale acquisitions in Cambodia, Colombia and the DRC since 2000.

The vast majority of this land – 14.2m hectares – is in the DRC, amounting to roughly 6 per cent of the nation’s surface area.

In Cambodia, 2.3m hectares – roughly 13 per cent of its land – has been involved in these deals, whereas in Colombia the figure is around 1.6m hectares, which is around 1 per cent of its area. In total, most of the acquisitions in these three nations were by international companies.

The researchers also found that the DRC has the largest amount of communal lands under threat.

Of the 14.2m hectares targeted for large land acquisitions in the DRC, they estimate that roughly 1m hectares – 7 per cent of the total – is land managed by Indigenous groups in the north and west of the country. These lands have predominantly been infringed by logging companies, with around 75 per cent of these deals being struck with international entities.

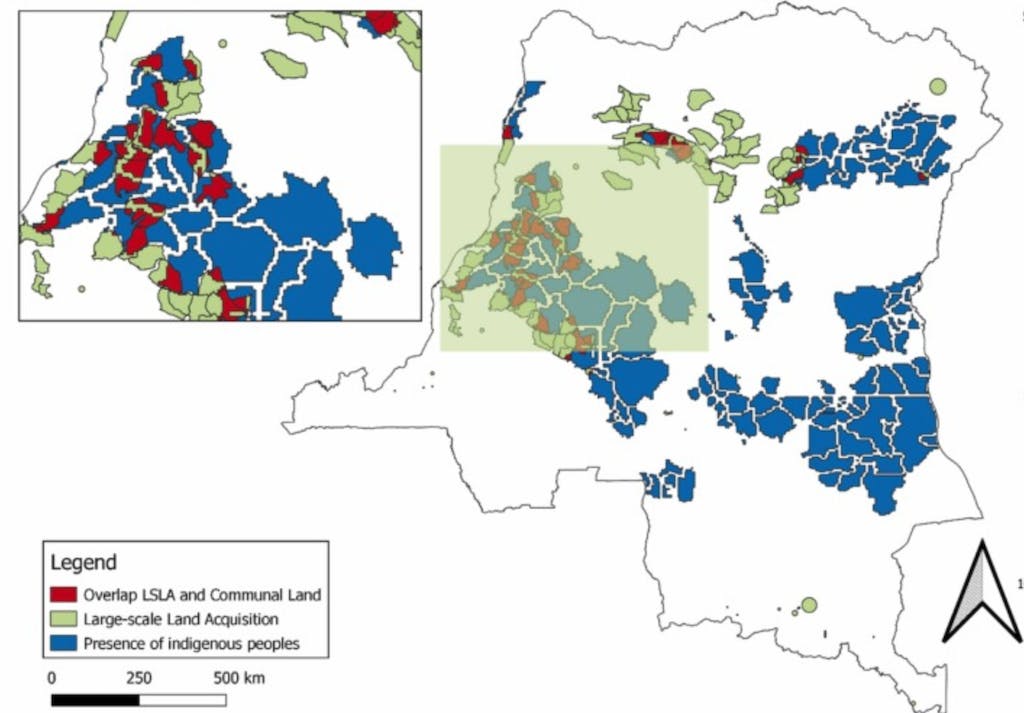

The blue areas in the map below indicate Indigenous peoples’ lands and the green areas show the locations of large-scale land acquisitions in the DRC. Red indicates the areas where there is a risk of overlap between the two.

Map of large-scale land acquisitions (green) and lands inhabited by Indigenous people (blue) in the DRC, with the overlapping areas shown in red. Source: Rincón Barajas et al. (2024)

In Colombia and Cambodia, where there are more legal protections in place, the areas of communal land infringed upon are lower – 53,369 hectares and 43,150 hectares, respectively, the study says. This equates to 3 per cent of the leased land in Colombia and 2 per cent in Cambodia.

The authors highlight the situation in the DRC as particularly “alarming”.

However, they note that their finding of 1m hectares of overlap is only an estimate, based on the presence of Indigenous people in certain regions and extrapolations of total communal land use from detailed mapping in a smaller area. (For Colombia and Cambodia, the figures are based on legally defined communal lands.)

This is due to the lack of firm definitions of communal land in the DRC, as Kubitza explains:

“You don’t have exact numbers because if you don’t have any progressive legislation, you also don’t have a lot of mapping being done – so you have to rely on estimates.”

Dr Raymond Achu Samndong, a monitoring, evaluation and learning manager at the International Land and Forest Tenure Facility, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the 1m hectare figure could be an underestimate, given the size of the country and the problems it faces.

“Land grabbing is a growing phenomenon in the DRC,” he says, pointing to communities with whom he has worked where the government has allocated large tracts of land for concessions and the affected communities were not informed.

He adds that that the country’s inaccessibility makes monitoring and enforcing land rights difficult:

“You have statutory and customary law that conflicts in some areas where the government has limited access and control.”

In areas where customary local chiefs are essentially the land owners, they have also been known to participate in and profit from “land grabbing”, Samndong says.

Underestimates

The study highlights how the recognition of collective land ownership can help to insulate communities from “land grabs”. However, the researchers also acknowledge the limitations of such recognition.

As in much of Latin America, Colombia has provided clear recognition of communal rights, with roughly one-third of the nation’s land falling under Indigenous and Afro-Colombian control. Yet estimates suggest that up to 9.43m hectares of the nation’s communal lands are still not legally recognised.

In Cambodia, too, the study authors accept that their assessments of communal lands being encroached upon by business interests are likely to be underestimates.

A UN report in 2020 found that despite Cambodia being home to 455 Indigenous communities, only 30 Indigenous land titles had been handed out by the government.

Luciana Téllez Chávez, an environment researcher at Human Rights Watch who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that while the legislation exists to recognise communal ownership in Cambodia, “the implementation of that legislation is lagging and the process is onerous”. She adds:

“Any study that is only assessing overlap between formally recognised Indigenous territories and land acquisitions would be missing most of the picture, as most territories have not been formally recognised.”

The new paper notes this shortcoming. The researchers also use data on officially recognised Cambodian Indigenous groups and find that around one-third of them are based within the sites of large land acquisitions.

They note that while “more extensive and detailed data are missing”, the impact of land acquisitions on communal areas could be larger than their initial results suggest.

Kubitza and his colleagues highlight that frameworks for states and companies to guide their use of land already exist. They stress that global supply chain regulation – of the kind being rolled out for forest products in the EU – could help to protect communities from land grabs if properly enforced.

In the DRC, Samndong says there have been “baby steps” towards progress from the central government, with the development of a community forest law and a new land law in the works.

Carbon offsets

The study also highlights the mounting pressure placed on communal lands by foreign governments and companies seeking to meet their climate goals by purchasing carbon offsets from overseas.

Carbon offsetting involves an entity paying for emissions to be reduced somewhere else, for example by preserving trees that can absorb carbon dioxide (CO2), while it continues to produce its own emissions.

The researchers point to specific carbon-offsetting projects in Cambodia and the DRC that have infringed on forest communities. These communities often have little understanding of the projects and derive few, if any, benefits, the researchers say.

Téllez Chávez, whose own work has identified human-rights violations at a forest offsetting project in Cambodia, says the research is “right to note carbon-offsetting projects as a potentially important driver of large-scale land acquisitions”. The Cambodian government plans to expand offsetting projects across much of the country’s protected areas.

Kubitza says this trend does not sit well with a vision of a global “just transition”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It cannot be that people who conserve forests for centuries don’t receive anything and investors just come in and make money with these kinds of business models.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.