Scientists have discovered 1,800 major sources of methane related to the exploitation of oil and gas. This relatively small number of super-emitters disproportionately account for a large percentage of global methane emissions, according to a report published in the journal Science.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

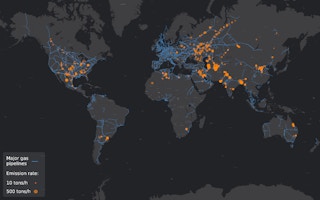

Using satellite imagery produced daily over two years, the researchers mapped large methane plumes across the globe. Nearly two-thirds of these massive emissions clouds were attributed to oil and gas exploitation and transmission. The team of French and American researchers estimate that these “leaks” have a climate impact akin to the circulation of 20 million vehicles over the course of a year.

Ultra-emitters detected by the satellite platform, TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) are mostly concentrated in Turkmenistan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Iran, Algeria, and parts of the United States, according to the findings. These super-emitters are responsible for about eight million tonnes of methane per year.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a strong climate impact. Globally, nearly 350 million tonnes of anthropogenic methane are released into the atmosphere each year, with about a third coming from the fossil fuel industry. Methane emissions come from waste or during equipment maintenance or failure, amounting to very large leaks.

Stemming the unnecessary releases of this pollutant from oil and gas production could lead to faster reductions in atmospheric concentrations and make achieving global climate goals more feasible, the report said.

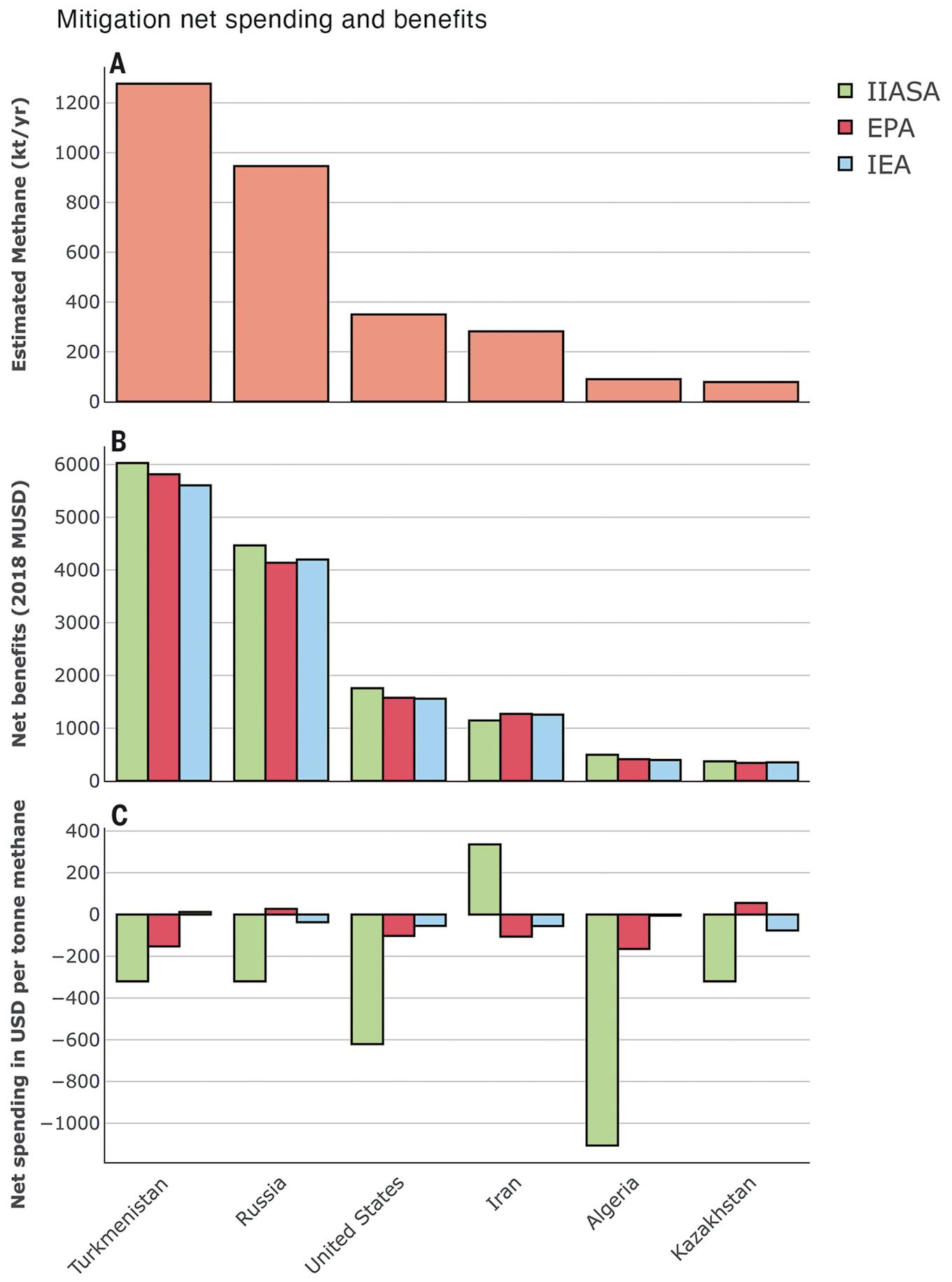

“Mitigation of ultra-emitters is largely achievable at low cost and would lead to robust net benefits in billions of US dollars for the six major producing countries when incorporating recent estimates of societal costs of methane,’’ the report said.

(A) Estimated methane emissions from ultra-emitters in the oil and gas sector in kilotonnes per year; (B) net societal benefits of mitigation of ultra-emitters, including monetized environmental impacts; and (C) net mitigation costs per ton for ultra-emitters without environmental benefits. MUSD, millions of US dollars. Image: Science, 4 February 2022.

The authors include researchers from Kayrros SAS, a French geoanalytics firm, and Riley Duren, chief executive officer of non-profit Carbon Mapper.

“The creation of a global inventory of methane ultra-emitters provides crucial information for targeting the strongest emitters,” wrote Felix Vogel in a related paper. “This should be a useful arsenal for policymakers to enact effective regulations to combat climate change and alleviate climate-related economic calamity in the long run.”

National plans

More than 100 countries signed a pledge in November to slash the potent greenhouse gas by 30 per cent by 2030 from 2020 levels. This could eliminate over 0.2 degrees Celsius of warming by 2050. The signatories represent nearly half of global anthropogenic methane emissions and over two thirds of global GDP.

Only one ultra-emitter—the US—out of the six identified in the Science report, is a signatory. Meanwhile, Russia, India and China have not signed the methane pledge, despite being three of world’s top three emitters.

Plans to cut methane emissions and the technical or financial support that countries may need to achieve targets, were discussed in January by ministers from the US, China, European Union, United Kingdom and 20 other countries that are largely responsible for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions.

India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia and Saudi Arabia—nations still heavily reliant on fossil fuels—also attended the virtual summit chaired by US special envoy for climate, John Kerry.

Kayrros SAS detected the potent greenhouse gas from China’s main coal-producing region last month, according to Bloomberg. One plume spotted on 21 December had an estimated emissions rate of 68 metric tonnes of methane an hour, while another seen on 4 December had an estimated rate of 53 tonnes an hour, according to the firm’s satellites. They were the second and third worse cases of methane pollution identified by satellite in China last year.