From supercharging extreme weather events to boosting the spread of infectious diseases, climate change is already having a huge impact on human health across the world.

But this impact is not being felt equally. A growing body of research suggests that the world’s most disadvantaged people are also the most vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change and the least likely to be able to adapt.

Gender is just one of many factors that can influence a person’s standing in society. This in-depth explainer looks into how climate change can have differing impacts on the health of men and women around the world.

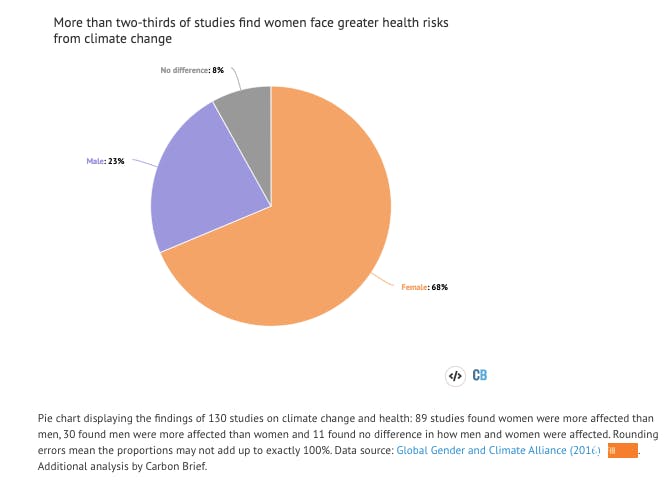

An analysis of 130 peer-reviewed studies – visualised below on an interactive map – finds that women and girls often face disproportionately high health risks from the impacts of climate change when compared to men and boys.

The analysis shows that 68 per cent (89) of the 130 studies found that women were more affected by health impacts associated with climate change than men.

For example, it shows women and girls are more likely to die in heatwaves in France, China and India and in tropical cyclones in Bangladesh and the Philippines. In many world regions, women are more likely than men to suffer poor mental health, partner violence and food insecurity following extreme weather events.

However, in some cases, men can face higher risks. For example, several studies suggest men face a higher risk of suicide following extreme weather events and are more at risk of certain health issues associated with working outdoors.

Mapped

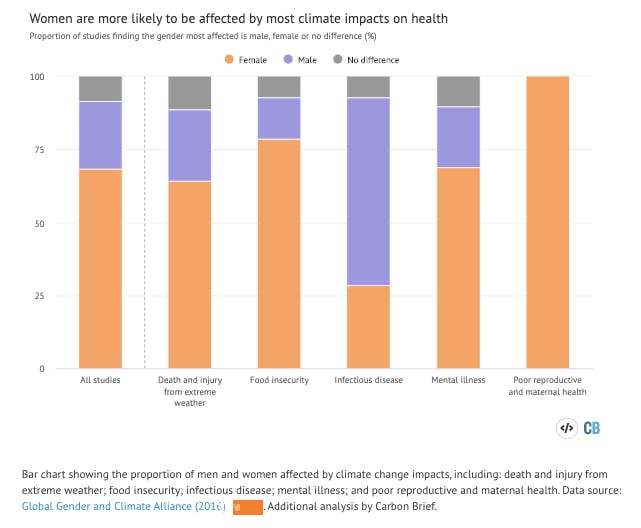

The map below displays 130 studies that investigate how the health of men and women is affected by impacts associated with climate change. These impacts include: death and injury from extreme weather; food insecurity; infectious disease; mental illness; and poor reproductive and maternal health.

On the map, each icon represents one study. The colour of the icon indicates whether the study finds that women (orange) or men (purple) are most affected by the climate change impact. (Grey indicates there is no difference between men and women.)

The data comes from a 2016 research report on gender and climate change authored by Dr Sam Sellers, a climate change and health researcher formerly based at the University of Washington.

The report itself was commissioned by the Global Gender and Climate Alliance, a UN-NGO alliance focused on gender and climate change. (The report focuses on the social construct of gender, rather than biological sex.)

To collect the data, Sellers carried out an extensive literature review to find any study mentioning gender alongside climate change or its associated health impacts from 2005-16. For this article, relevant papers published since 2016 have also been added to the review.

The review also includes studies that do not specifically reference climate change, but investigate impacts that are known to be affected by it.

This includes, for example, a study finding that women were more likely to have died than men in a 2010 heatwave in Ahmedabad, India. (Though the study does not specifically cite climate change as the cause of death, it is known that heatwaves are becoming more likely and intense as a result of warming.)

Out of the 130 climate and health studies analysed, around 68 per cent (89) found that women were more affected than men.

Across the world, women are more likely than men to be affected by climate-related food insecurity and are also more likely to suffer from mental illness or partner violence following extreme weather events.

The heightened risks faced by women most often reflect their standing in societies around the world – rather than a physiological difference between men and women, explains Kim Van Daalen, a PhD student in global public health at the University of Cambridge. (In February, Van Daalen wrote a letter to the Lancet on how women can face disproportionate health risks from climate change.) She tells Carbon Brief:

“It has more to do with societal roles rather than physiological differences. I tend to say climate change is exacerbating existing inequalities, be that gender or other inequalities.”

One exception to this is climate change’s impact on maternal health, she says. The review shows that pregnant women often experience heightened health risks and reduced access to reproductive and maternal care services as a result of climate change impacts.

Meanwhile, 30 of the climate and health studies included in the review found that men were more affected than women.

According to the review, men are more likely than women to face a higher risk of suicide following extreme weather events and, in some regions, are more likely to be killed in floods and during wildfires. Van Daalen says:

“In some places, boys and men face increased risks to the climate change impacts on health – and that is particularly, for example, in regions where they may be exposed to extreme weather events because they are working outside.”

In addition, 11 studies found there to be no difference between how men and women were affected.

Overall, there has been little research into the gendered impacts of climate change – making it difficult to draw firm conclusions, says Van Daalen:

“Most of the studies that are being done are based in low- and middle-income countries. But I think there hasn’t been enough research to assume that gender inequalities are higher for low- and middle-income countries. I think the gender differences are definitely there in high-income countries, we just haven’t researched them enough.”

In addition, there has been even less research into the health impacts of climate change for non-binary and transgender people, she adds:

“For non-binary people, there’s literally no data on that and I think that’s quite problematic.”

Extreme weather

Across the world, climate change is causing many extreme weather events to become severe and more likely to occur.

This is particularly true for heatwaves. For example, research finds that this year’s long-lasting Arctic heatwave was made 600 times more likely by climate change. Research also shows that the northern hemisphere’s unprecedented 2018 heatwave would have been impossible without climate change.

There is growing evidence, too, to suggest climate change is playing an increasingly large role in more complex extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, droughts and wildfires.

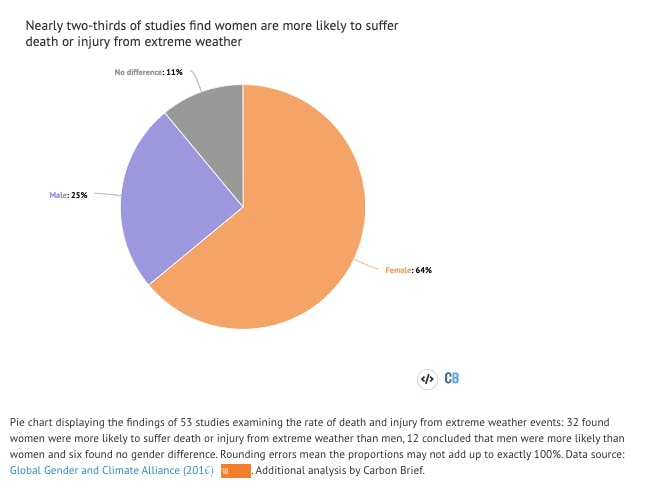

The analysis includes 53 studies that examine rates of death and injury for men and women during extreme weather events.

Almost two-thirds (34) of these studies found that women were more likely to suffer death or injury from extreme weather than men, 13 concluded that men were more likely than women and six found no gender difference.

The factors behind who is most likely to die in extreme weather events vary from country to country, says Van Daalen:

“In a lot of regions, women and girls are more impacted – but in other regions, it’s actually boys and men that are more impacted. It’s very regionally specific and dependent on the roles people take up in society in each region.”

In many low- and middle-income countries, women’s lower societal status can put them at greater risk of dying during extreme events, she says.

For example, some research suggests that, in Bangladesh, social expectations placed upon women could lessen their ability to survive tropical cyclones and flooding events.

According to one study conducted in Bangladesh, cultural expectations for women to wear the sari – a long dress that can restrict movement – could make it more difficult for women to escape from floodwaters.

Another study found that, after a 1998 flood in Dhaka, women were less likely than men to leave their homes to seek medical help. The researchers suggest that this was likely linked to cultural norms that restrict women from leaving their homes without a male chaperone.

In addition, a study published in 2016 drawing on data from 85 low- and middle-income countries over two decades found that women were more likely to be killed by extreme weather events in countries where their socioeconomic status was below that of men.

However, other studies suggest that women in high-income countries could also be more at risk than men of dying in certain extreme events.

For example, a string of research papers have found that women are more likely to die than men in heatwaves in France. One study, published in 2012, found that female deaths were more likely in nine European cities, including London, Paris and Rome.

The reasons why women in Europe could be more at risk from heatwaves are not yet fully understood. However, several research papers suggest that older women with underlying health conditions could be particularly vulnerable to increasing heat in Europe.

By contrast, several studies in the US and Australia have found that men are more likely to die in heatwaves than women.

For example, a US national health report found that, from 2006-10, the death rate from extreme heat was 2.6 times higher for men than women across the country.

One reason men could be more at risk from heat in the US is the country has a high proportion of socially-isolated elderly men, Sellers says in his review:

“In the US, the vulnerability of males to heatwave deaths is attributed in part to the social isolation that many elderly men experience.”

Another reason could be that, in the US and other high-income countries, men more frequently work and spend leisure time outside and so could be more exposed to increases in heat, says says Prof Kristie Ebi, a researcher in public health and climate change from the University of Washington. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Retired men can be in the category of people more at risk from heat. Often they go out in the afternoon, sit in the park and spend time outdoors – and so have higher heat exposure than women who stay indoors.”

A study published in 2018 found that, across 50 different US cities, men faced a higher risk of outdoor heat exposure than women.

Men in the US, Australia and China can also face a higher risk than women of dying in floods, according to several studies. One reason for this could be that men are more likely to assist in rescue efforts, research suggests.

In addition to raising the risk of death, extreme weather events can also raise the risk of injury and personal safety issues. The review finds that women are often disproportionately affected by many of these health impacts.

For example, after Hurricane Katrina struck the US city of New Orleans and its surrounding areas in 2005, researchers found that women faced higher rates of partner violence and sexual assault.

Further research in New Zealand found that cases of domestic violence increased after flooding in 2004. A study for ActionAid Bangladesh also observed an increase in violence against women after flooding in 2007.

Food insecurity

Climate change is affecting food insecurity across the world in a number of ways. Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns are affecting crop yields, while extreme weather events, such as droughts, are causing unpredictable harvest losses.

In low- and middle-income countries, food insecurity can be strongly linked to poor health.

The review finds that, in low- and middle-income countries, climate-driven food insecurity can have a disproportionately large effect on the health of women.

Out of 14 studies examining links between climate change, food insecurity and health, 79 per cent (11) found that women were more affected than men. (Two studies found men were more affected than women and one found no difference in the impact on men and women.)

Understanding why women are more affected by climate-driven food insecurity requires an understanding of historic social hierarchies in many low- and middle-income countries, says Dr Raman Preet, a global health researcher at Umeå University in Sweden. She tells Carbon Brief:

“If there is less food available, then who gets to eat more food? In a lot of cases, it’s men. That’s not new, these gender roles have been around for thousands of years.”

Studies show that, during times of climate-driven food insecurity, women were more likely than men to forgo food in India, Iran, South Africa, Ghana and Nicaragua.

In many regions, female children are also more likely than male children to go without food, says Preet:

“There’s always a preference for how you feed. This has gone on for centuries. Are we ready to accept that if there’s food insecurity then the girl child gets lower priority?”

For example, a study in the Philippines found that, in the months following typhoons, female children face a greater risk of infant mortality, whereas male children do not face a heightened risk. The researchers attribute this to the preferential feeding of male children when resources are scarce.

Though women are often more affected by food insecurity, there are certain cases where men can bear the brunt of the impacts.

A study in South Greenland found that men are finding it more difficult to hunt Arctic prey as a result of population declines linked to climate change. According to the study, this is increasing men’s economic reliance on their female partners. (However, the study also found that hunting failures were linked to increases in domestic violence.)

Infectious disease

Rising temperatures are causing wildlife and the diseases they carry to move into new areas. This, in turn, is heightening the susceptibility to some vector-borne and other infectious diseases.

For example, research published in 2019 found one billion more people could become exposed to mosquito-borne diseases by 2080 as result of rising temperatures.

In May, Carbon Brief reported on how warming temperatures could also heighten exposure to thousands of novel animal-borne – or “zoonotic” – diseases. (Covid-19 is an example of such a disease.)

In addition, research shows that sea level rise could also play a role in heightening exposure to infectious diseases.

This is because some infectious bacteria thrive in slightly salty – or “brackish” – water. Sea level rise is causing brackish water to move closer to where people live, heightening their exposure to disease.

Ocean warming could also aid the spread of marine bacteria, research shows.

The review looks at how several infectious diseases that are known to be affected by climate change are currently impacting men and women.

Out of 14 studies, 64 per cent (9) found that men faced a higher risk than women of contracting infectious diseases. (Four studies found women faced a higher risk, whereas one study found no difference between the genders.)

Men are often at a greater risk of being exposed to infectious diseases because they more frequently work and spend leisure time outdoors, Sellers says in his review:

“There is some evidence that males are at greater risk of schistosomiasis infection than females, particularly at younger ages as boys tend to spend more time playing near water where the disease is transmitted.”

Schistosomiasis – also known as “bilharzia” – is a debilitating disease caused by parasitic worms that pass from person to person in contaminated water. It mostly affects tropical Africa. Research shows that rising temperatures are likely to increase transmission of schistosomiasis.

Several studies in North America have also found that men are at a greater risk of suffering from Lyme disease, a bacterial infection spread through tick bites. One reason for this is because men spend more time working outdoors in wild environments and so are more likely to come into contact with ticks.

Research finds that Lyme disease exposure could “substantially increase” further northwards in the US and Canada as a result of warming temperatures.

While men face a heightened risk of disease when outside, women can face heightened risks at home, the review shows.

Several studies have found that women face a greater risk of malaria than men. One reason for this is that, in low- and middle-income countries, women can come into contact with contaminated water sources in and around the home, says Van Daalen:

“If you are surrounded by a lot of stagnant water sources, you are more likely to be exposed to the mosquitoes that carry malaria.”

Mental illness

The links between climate change and poor mental health are complex. Research suggests that extreme weather events can aggravate the risk of mental illness through bereavement, injury and economic losses.

Prof Helen Berry, inaugural professor of climate change and mental health at the University of Sydney, explained the links in a guest post for Carbon Brief in 2018. She said:

“Climate change is increasing the frequency and ferocity of weather-related extremes year-on-year. More people are being exposed – or, worse still, the same people are exposed more frequently – to injury, loss of homes and businesses, environmental damage and even loss of lives.”

“All of these have profound, often long-term effects on mental health. Yet there remains relatively little research on this topic and even less commitment to doing anything about it.”

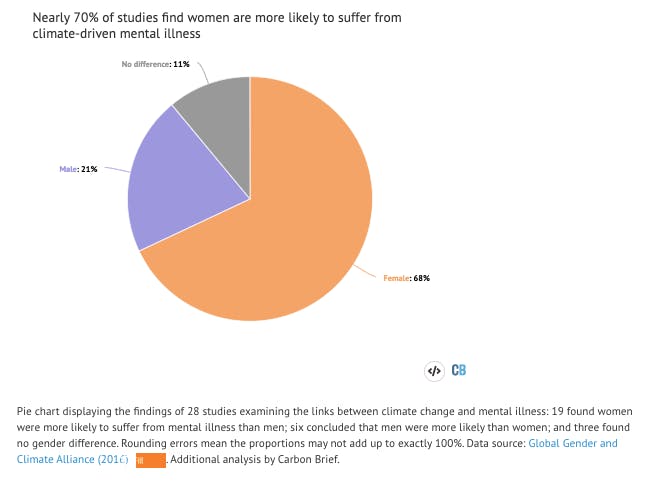

The review includes 28 studies that examine links between climate change, mental illness and gender.

Out of these studies, 68 per cent (19) found that women are more affected than men. Meanwhile, six studies found men were more affected than women and three studies found no gender difference.

Studies show that women faced a greater risk than men of suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following tropical cyclones in the US, Australia and Myanmar, and following flooding in the UK and China.

The reasons why women tend to be more likely than men to suffer from PTSD after extreme weather events are not fully understood.

The World Health Organization notes that women are the largest single group of people to be affected by PTSD – and that this is linked to a high prevelance of sexual violence worldwide. Studies show that the risk of sexual violence can rise during and after extreme weather events (see: Extreme weather).

In addition to PTSD, studies also show that women tend to face a higher risk of depression and emotional distress following extreme weather events.

By contrast, several research papers have found that men can face a higher risk of suicide than women following extreme weather events.

Research in both India and rural Australia suggests that male farmers could be at a particularly high risk of suicide after events such as droughts, which can cause rapid crop failures.

For example, one study in Australia found that the risks facing male farmers could in part be attributed to “a dominant form of masculine hegemony that lauds stoicism in the face of adversity”. A study in India, meanwhile, found the risks facing male farmers were linked to unfavourable cash-crop prices and debt.

In addition, research in South Korea found that increases in daily temperature were associated with increases in suicide rates for men from 2001-5.

Across the world, the suicide rate for men is twice as high as for women.

Women and others that carry children are uniquely threatened by climate change’s impact on reproductive and maternal health.

Climate change threatens reproductive and maternal health in two main ways. First, it can raise the health risks for expecting mothers and foetuses. Second, it can limit access to reproductive and maternal health services, explains Van Daleen:

“Climate change is increasingly putting strains on healthcare systems. It can quite directly destroy hospitals through extreme weather events, but it can also just indirectly put more strain on healthcare services.”

“When this happens, what we generally see is that reproductive and maternity health services are most impacted because they are already undervalued in comparison to other services and so not prioritised.”

The review includes 21 studies that explore how climate change can affect reproductive and maternal health.

Studies show that exposure to extreme weather events can heighten health risks for expecting mothers and their foetuses.

For example, maternal and newborn health problems have been linked to hurricane exposure in Texas and Florida and heatwave exposure across 19 African countries, Italy and Spain.

The exposure of expectant mothers to heat, in particular, is known to have an impact on newborns, says Ebi:

“We do know there’s an impact on the growing foetus from studies that are showing that there is an increased incidence of problems such as low birth weight.”

In addition, studies in Haiti and Thailand show that exposure of pregnant women to infectious diseases, such as malaria, could heighten the risk of miscarriage and other serious maternal health issues.

(Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that is being boosted by climate change in some regions. See: Infectious diseases.)

A study published in 2007 found that young women struggled to access reproductive health services following Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

However, further research into how climate change could affect access to reproductive healthcare is so far lacking, Sellers says in his review.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.