A new monitoring platform that uses satellite imagery to track dam reservoir levels on the Mekong can shed light on the contentious issue of how the river’s precious water is stored, and the effects of climate change.

The disruption to water and sediment flows along the river resulting from the proliferation of dams “is causing the Mekong to die a death of a thousand cuts,” said Brian Eyler, director of the Stimson Centre’s Southeast Asia Programme.

He said the Mekong Dam Monitor, launched by the Stimson Center, promises to improve water resource management in the region and help researchers document changes to the climate.

Up to 60 million people depend on the Mekong for food and livelihoods. The 4,350-kilometre waterway originates in China, where it is known as the Lancang, before flowing through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

China has built 11 hydropower dams, and along the full length of the Mekong and its tributaries, at least 102 dams impede flow according to the Stimson Center’s Mekong Infrastructure Tracker.

This is significant because, in the dry season, as much as 70 per cent of the water in the Mekong downstream at Chiang Saen comes from China.

Understanding the effects of climate change

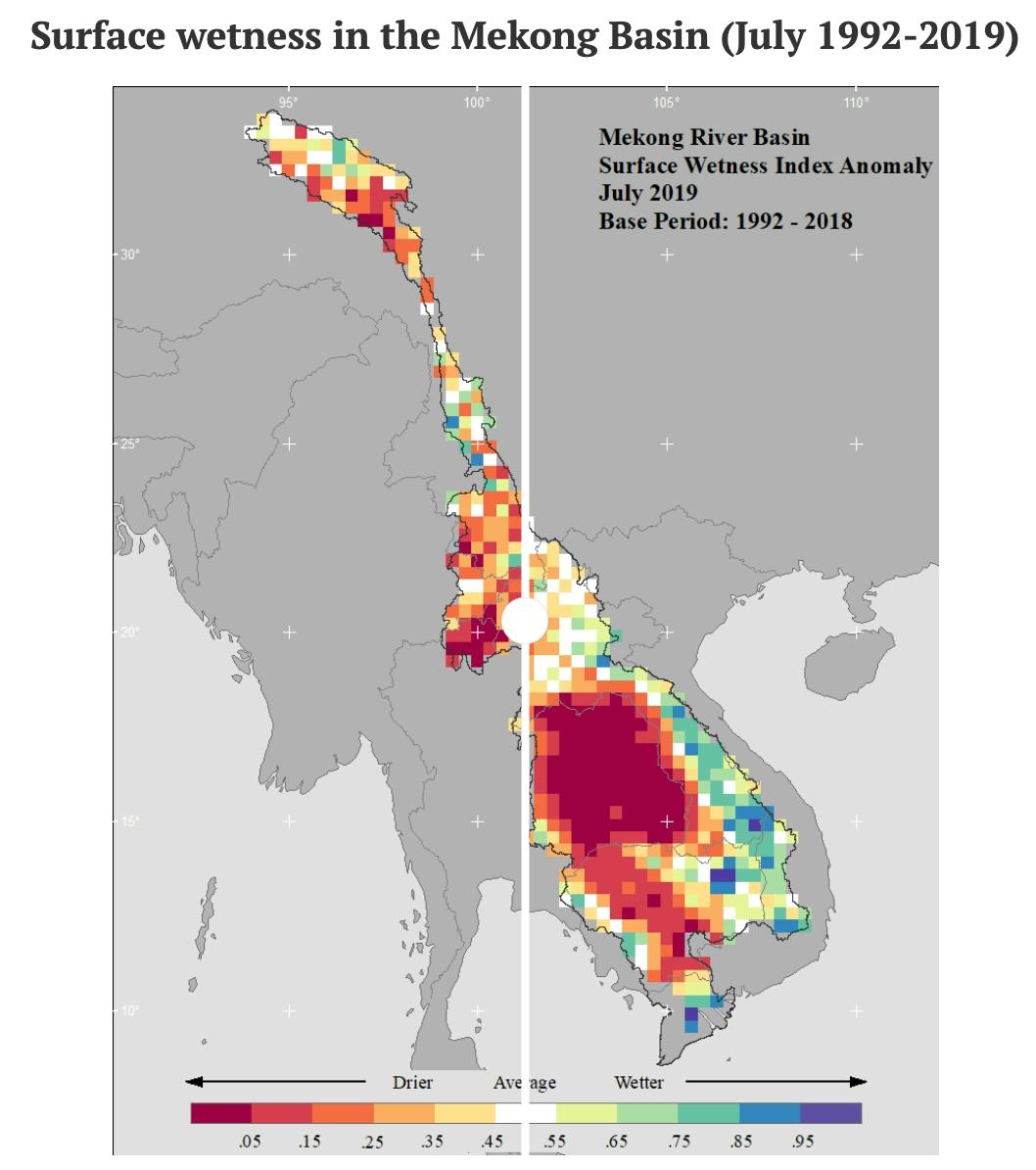

As well as tracking reservoir levels, the Mekong Dam Monitor uses satellite imagery to reveal the “surface wetness” — relative wetness or dryness — of different parts of the basin. This provides information on how the dams affect river flow.

Source: Mekong Dam Monitor. Data from the Mekong Dam Monitor shows that patterns of surface wetness have changed markedly since 1992.

Eyler said the new tool provides data on melt rates in the snow-covered portions of the river’s upstream reaches. Researchers can combine data from the monitor with that from Eyes on Earth, a US-based consulting company that uses satellite images to address climate issues.

The company, a partner of the Stimson Centre, is approaching 30 years of continuous satellite monitoring to understand climate change.

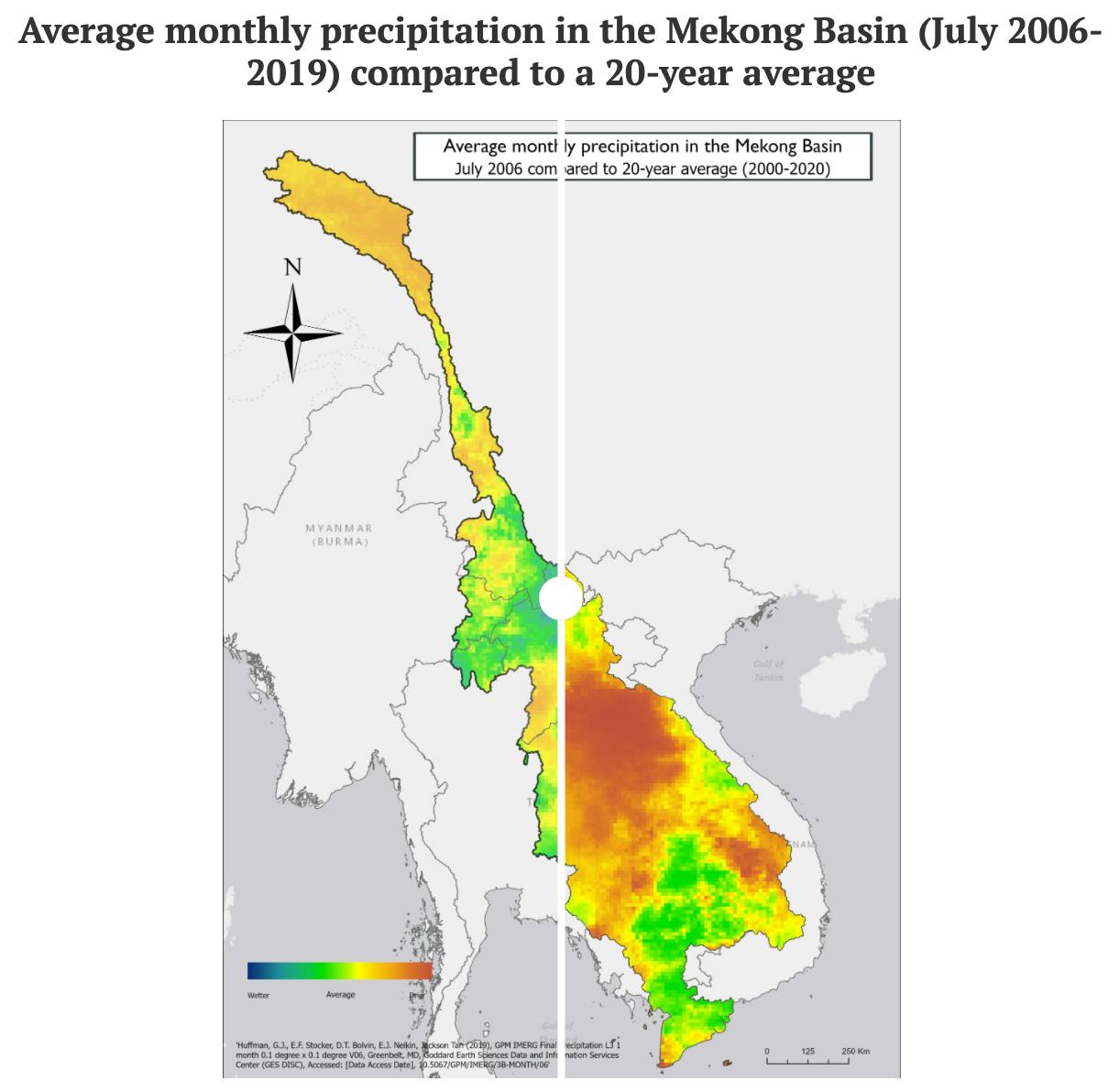

“To find climate change effects in the Mekong Basin, a user of the Mekong Dam Monitor could start with the climate anomaly maps which start in 1992 and run through the present day,” said Eyler. The maps show wetness, temperature, precipitation and snowmelt.

Source: Mekong Dam Monitor. Data from the Mekong Dam Monitor shows that patterns of precipitation have changed markedly since 1992.

The two most apparent factors of climate change are general trends and variations of extreme events, according to Alan Basist, president of Eyes on Earth. He added that as the most pronounced impacts of climate change have become evident in the last 30 years, their data “provides a meaningful period of record to identify significant trends in surface wetness, surface temperature or snow cover”.

“The other feature we can monitor, which directly relates to climate change, is the variation in extreme events and their frequency,” Basist said, citing the Tonle Sap lake as an example of an area where the frequency of severe drought is changing.

A study released by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in December 2019 suggested the gravest threat to the Mekong delta in Vietnam, much like the Tonle Sap lake, is sediment starvation caused by upstream dams, rather than rising seas.

Gary Lee, Southeast Asia program director at International Rivers, said climate change and large-scale dams on the Mekong mainstream and tributaries make the river’s flows and water levels unpredictable.

“Large dams upstream are significantly reducing the amount of sediment reaching the Mekong delta, with major impacts on soil fertility, rice and agricultural production and fisheries, which provide significant sources of income and livelihoods for millions of people living in the delta,” he said.

Major dams on the Mekong river. Following severe droughts that affected lower Mekong countries in recent years, China has been called on to offer transparent information about its dams.

According to a Mekong River Commission study, modelling on the current and planned Mekong dams finds that sediment reduction could be as high as 97 per cent by 2040. This advisory body includes Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand.

“The Tonle Sap is dying because of Mekong dams that prevent water from reaching the lake,” said Cambodian-American Sophal Ear, associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College, Los Angeles.

“We all know how much protein from fish in the Tonle Sap means to Cambodians, and yet there’s seemingly no recognition that the dams are collapsing catches.”

China has repeatedly claimed that its dams prevent droughts and flooding and do not negatively affect the lower Mekong. In October, China agreed to release year-round water data through the Mekong River Commission from two hydropower stations.

“The positive benefits of upstream Lancang river hydropower on downstream Mekong neighbours are clear and obvious,” said the China Renewable Energy Engineering Institute in a December report.

River of rhetoric

Severe droughts have stripped away fishing and farming communities’ livelihoods in lower Mekong nations in recent years. In response, China has been called on to offer transparent information about its dams.

Eyes on Earth published a study in April 2020 claiming that Chinese dams along the Mekong held backwater during life-threatening periods of drought caused by the monsoon’s failure in 2019.

In response, the Mekong River Commission said the report did not “provide robust scientific evidence that the storing of water in Chinese reservoirs caused the exceptionally low flows in the LMB [Lower Mekong Basin] at Vientiane in 2019 and 2020”.

Another group of researchers made a similar criticism, arguing that data was being overinterpreted for political ends.

During Cambodia’s monsoon months, the river swells, expanding the Tonle Sap lake to five times its dry-season levels, depriving it of nourishing sediment that forms its ecosystem’s foundation.

Consequently, fish breeding plummets and the communities lining the lake’s shore struggle to survive.

In early 2020, Vietnam suffered the double blow of drought and saltwater intrusion into its Mekong delta provinces. Fishing and agricultural communities were devastated by the loss of crops and drinking water contamination.

A December report, coordinated by Vietnam’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said 1.3 million people fled the area over fears of natural disasters such as droughts.

A paradox in China’s energy machine

China’s state media has claimed that upstream dam regulations are beneficial to downstream countries because they reduce monsoonal floods and release water during the dry season.

Eyler said there is “no evidence that these restrictions or releases are beneficial to the region”.

“No stakeholders downstream are calling for such regulation,” he said. “In fact, we’ve heard from dam operators downstream whose operations are impacted by upstream restrictions, and this is affecting their profit margins.”

Eyler added that the new monitoring tool provides evidence that “China’s upstream dam operations are purely coordinated and optimised for the purpose of producing a maximum amount of hydropower at a time when the price of electricity is high in China.”

Cecilia Han Springer, a senior researcher with the Global China Initiative at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Centre, said upstream impoundment has severe effects on downstream countries’ ability to manage their water.

However, Springer is more focussed on Mekong dams outside China. She has so far identified over 1,000 dams – on both the mainstream Mekong and its many tributaries – in lower Mekong countries, including a profusion of smaller hydropower projects involving Thai and Chinese developers.

There are 11 mainstream dams in various stages of planning or completion on the Lower Mekong. The Nam Ou, a vital river that feeds the Mekong, has seven dams, all with Chinese construction or development involvement.

She says it’s difficult to parse the effects of climate change from smaller hydropower projects. Still, a recent paper looking at emissions from reservoirs in the Mekong region found some, including for hydropower projects, release greenhouse gas emissions on a par with some fossil fuel plants.

This story was published with permission from The Third Pole.