Ana Maria dos Santos Suares, a farmer in Timor Leste’s Ermera municipality, has much more free time on her hands now than she did a few years ago. Where she once spent day after day weeding in her maize fields, she now only needs to do so once in a planting season.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“We use the remaining time to plant other crops such as potato and taro, cook, feed the pigs, look after the children, and rest,” says Suares in a documentary by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

This change is thanks to a project FAO has been conducting in districts across Timor Leste since 2013 to promote an alternative farming method to burning the land, ploughing it, and weeding it regularly.

Instead of this traditional practice, FAO encourages three strategies: First, minimising soil disturbance by inserting seeds directly into the soil; second, covering the soil with a layer of crop residue, or mulch—this is what prevents weed growth—and third, planting a variety of crops on the soil.

Suares, who is one of several farmers involved in the FAO project, says that switching to these practices has improved the quality of maize on her farm. And because the mulch retains water for several weeks, she still gets a good yield even if there is a long drought, or seeds are planted late in the season.

She offers an analogy for the difference between traditional practices and the ones FAO advocates: “Just like humans will burn in the sun without clothes, the ground needs to be covered with mulch.”

Suares adds: “If we do not keep the soil fertile, then over time our children will have problems. They will not have enough food, and will suffer.”

An invisible crisis

This is a reality that FAO knows all too well, and is at the heart of its work to preserve and restore the health of the world’s soils.

The UN agency estimates that a quarter of the Earth’s surface—land that could feed 1.5 billion people—has already become degraded, and a further 24 billion tonnes of fertile topsoil are lost to erosion, deforestation, and unsustainable farming practices every year.

This boils down to one disturbing prediction: The world could have as little as 60 years of harvests left, a scenario that would have knock-on effects on global food security—as well as geopolitics and security—and affect the crucial role soil plays in regulating the global climate and maintaining biodiversity.

So what is a healthy soil? It is a complex measurement that involves assessing physical, biological, and chemical properties. According to FAO, the most relevant qualities are “nutrient availability, workability—that is, the readiness of the soil to be tilled and cultivated, contingent on factors such as water content and structural sability—oxygen availability to roots, nutrient retention capacity, toxicity, salinity and rooting conditions”.

Problems with soil health also take various forms ranging from nutrient loss, erosion, acidification, and contamination by pollutants and toxic chemicals, to name a few. Often, these go hand in hand; for example, when soil erosion takes place, the most fertile layer—topsoil—is the first to be lost, thereby reducing the nutrient content of the soil.

As David Montgomery, professor of earth and space sciences at the University of Washington, intones: “Soil health is like human health; it is hard to define, but you sure know when you don’t have it.”

Definitions may be elusive, but experts agree on two things: first, that intense, large-scale industrial agriculture has been a key driver of soil degradation in recent decades; and second, the world isn’t paying nearly enough attention to this looming crisis.

Yuji Niino, technical officer, FAO, explains: “We recognise that soil degradation is due to the loss of organic carbon.” Essentially, this is the sum of biologically diverse organisms found in the soil including microbes, fungi, invertebrates such as worms, slugs and insects, root matter, and decomposing vegetation.

Soil carbon is widely considered to be the most important component of soil because it is the main source of micro-organisms that live in the soil, determines the availability of nutrients for plant growth, and even affects how resistant soil is to erosion.

In the past, traditional farming methods would return organic carbon to the soil after each harvest by applying manure or crop residue, says FAO’s Niino.

“But modern, mechanised, industrialised farming has eliminated this,” he notes. Today, a major portion of crop residues is usually used for other purposes such as making biofuels and animal feed.

“Three to four decades of not returning this organic matter to the soil has almost completely depleted the soil organic carbon in some regions in Africa and South Asia as well as tropical semi-arid regions with intensive farming practices,” says Niino.

The consequences of soil degradation are severe, and range from exacerbating global hunger to causing biodiversity loss, and contributing to climate change when soil carbon is released into the atmosphere.

A 2015 report by Economics of Land Degradation, a global initiative, estimates that land degradation costs the global economy between US$6.3 trillion and 10.6 trillion annually.

Given the severity of soil degradation and its impacts, and the rapidly depleting lifespan of the world’s soils, Niino observes that the issue “has been ignored for a long time”. There was virtually no international focus on the issue until 2002, when the United Nations declared December 5 as World Soil Day.

More than a decade later, 2015 was designated as the International Year of Soils.

Niino explains that a lack of global attention to the issue of soil degradation is likely because it is a slow-onset and relatively invisible crisis. There have been decades of heated debate about water scarcity because of falling water levels, drying lakes and riverbeds, and dying vegetation are instant and noticeable symptoms of the problem, notes Niino.

“In contrast, farmers and everyone else cannot see the immediate impact of land degradation and soil productivity losses,” he says. “They may notice declining yields if they compare to the past decade or two, but it’s not an immediate impact they can see.”

“

Soil health is like human health; it is hard to define, but you sure know when you don’t have it.

David Montgomery, professor of earth and space sciences, University of Washington

Asia’s soil future

Niino notes that soil degradation is especially severe in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Years of mono-cropping staples such as rice and the rise of industrial agriculture—for example, a shift from traditional crops such as rain-fed paddy to cash crops such as palm oil, sugarcane, and cassava— in Southeast Asia have exacerbated soil degradation in the region.

Demographic and economic pressures such as urbanisation, population growth, and economic development have also led to land use change and put further pressure on Asia’s soil resources, says Niino. To promote sustainable soil management practies, FAO published a set of voluntary guidelines in 2017, which recommend best practices from both a technical and policy perspective.

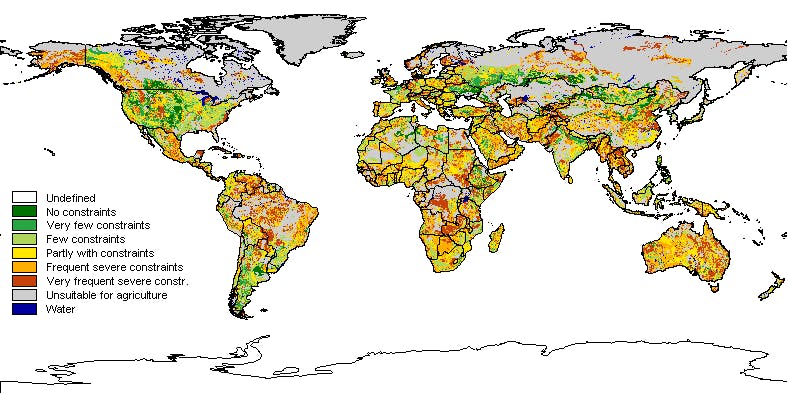

A global map of the constraints placed on soil health. Image: FAO

In a 2015 report on the State of the World’s Soul Resources, FAO notes that Asia has the highest percentage of human-caused land degradation of any region globally. Deforestation has been a key cause of this, followed by agriculture and overgrazing.

Currently, FAO says that for most criteria such as erosion, contamination, acidification and nutrient imbalance, the quality of soil is broadly poor and deteriorating. For soil carbon content, the status is classified as poor but variable.

A better way

To address the soil degradation crisis in Asia and globally, FAO has been working with governments and communities to manage soil more sustainably.

A key solution FAO has promoted is conservation agriculture, which entails the three principles the UN agency is promoting in Timor Leste and other project areas: no tillage—that is, disturbing or ploughing the soil—keeping the soil covered with crop residue or plants at all times, and growing a variety of crops on a rotational basis rather than constant cultivation of a single crop.

These practices improve the nutrient content of soil, increase its ability to retain moisture, and render it less vulnerable to erosion, among other benefits.

University of Washington’s Montgomery, who is also the author a book titled ‘Growing A Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life’, notes that these principles are an entirely different way of thinking about the soil because of the emphasis on restoring its health.

He adds that interviews with farmers across the world show that although it involves a significant departure from business-as-usual, the practice is gaining popularity.

There are two reasons for this, explains Montgomery: First, it helps them reduce costs. Because conservation agriculture is less labour intensive, and requires fewer fertilisers and agrochemicals—though it does require investing in new machinery to plant seeds without tillage and clearing cover crops —than traditional methods, farmers are able to save money in the long run when they switch to conservation agriculture.

Second, farmers are able to reap similar, if not larger, yields compared to traditional methods, notes Montgomery. Farmers in the pilot project conducted by FAO in Timor Leste have reported similar outcomes.

A no-till seed planter. Image: United Soybean Board, CC BY 2.0

Yet another unique feature of conservation agriculture is that it is suitable for all scales of operation ranging from smallholders to multinational agricultural giants, says Montgomery.

Even in commercial agriculture where economic reliance on a single agricultural commodity is core to the business, mulching and no-tillage agriculture as possible, he notes. And in these circumstances while it may not be possible to rotate the core crop, rotating the cover crops is a viable strategy.

“It’s possible to take same general principles and apply it to different farming systems,” says Montgomery.

A producer in Stanly County, North Carolina rolls down a cover crop just minutes before planting corn. The ‘blanket-like’ results of rolling provide season-long weed protection, moisture retention, and food for soil microbes. Image: NRCS photo, CC BY 2.0

From agribusiness giant Cargill, which tells Eco-Business that it grows legumes as cover crops on its oil palm plantations to reduce weed infestations, reduce soil erosion and increase nutrient availability, to agrotechnology firm Syngenta—controversial for its development of genetically modified crops—which has developed a machine which helps farmers plant seeds with minimal tillage and leave crops on the soil surface, conservation agriculture is gaining ground globally.

But if it is so easy and beneficial, why isn’t conservation agriculture the new normal for farming worldwide?

For FAO’s Niino, it boils down to a lack of understanding about this new system at all levels of the agricultural value chain, from farmers to businesses, to policymakers.

“You need to change the system, and need policy support in the form for subsidies for machinery and other things,” he notes. It is difficult to convince businesses and investors to take the leap into the new methods and technologies that support conservation agriculture, he notes.

This is slowly changing, as the market for the many machines to facilitate conservation agriculture expands, says Niino. Types of equipment this new paradigm entails include zero-tillage seeders which drill the seed directly into the soil, and knife rollers that crush residual vegetation instead of ripping it out, to name a few.

For Montgomery, a big part of the challenge to scaling up conservation agriculture lies in the fact that farmers may not always know how to adapt its broad principles to their local context and requirements. For instance, the same cover crops or strategies that work in Timor Leste might not work in Midwest America.

Because they are unsure, farmers may be hesitant to risk overhauling their practices, Montgomery explains. A key way to address this could be demonstration farms which showcase conservation agriculture techniques that have been successful for a particular location or industry, he says.

He adds that conservation agriculture adoption might also be slow because where big companies have aggressive armies of salesmen to hawk equipment such as ploughs, tractors, fertilisers and herbicides to farmers, there are no such economically-motivated advocates for conservation agriculture because it is more focused on specific practices and principles rather than equipment.

But Montgomery also notes that this is changing, pointing to agrotechnology multinationals such as Monsanto and Syngenta selling products that improve soil health.

“If big agriculture starts thinking of soil health, they might find the next generation of marketable products in that arena,” he says. “Savvy businesses will identify new opportunities as the philosophy of farming changes.”

Ripe for the picking

This is a view that global economic and private sector experts share.

In 2017, for instance, Norwegian shipping and energy advisory services firm DNV GL, Danish advisory group Sustainia and the United Nations Global Compact identified addressing soil degradation as one of the biggest market opportunities in a project called the Global Opportunities Report.

Emil Damgaard Grann, director of strategy, Sustainia, tells Eco-Business that soil degradation and other risks in its report were chosen on the basis that they are global in reach, are likely to affect humans now or within the next decade, and that there are opportunities to respond to the issue with definitive action.

“It is our ambition to show that even the toughest risks are avenues to explore profitable new markets and design innovative solutions,” he says. “Soil depletion made it into the report, as it is a neglected risk but still one that is needed to tackle in order to deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”

The SDGs are a set of 17 targets for global development that the world aims to meet by 2030, including ending hunger, poverty and gender inequality, promoting clean energy and climate action.

Many businesses are already working on this issue. Solutions showcased in the report include Singapore-based vertical farm Sky Greens, which grows leafy vegetables in high-rise energy and water-efficient towers; a variety of companies across the world which sell enzymes and microbes to restore soil health; and Nanoclay, a technology that can convert dry, sandy soil to arable land.

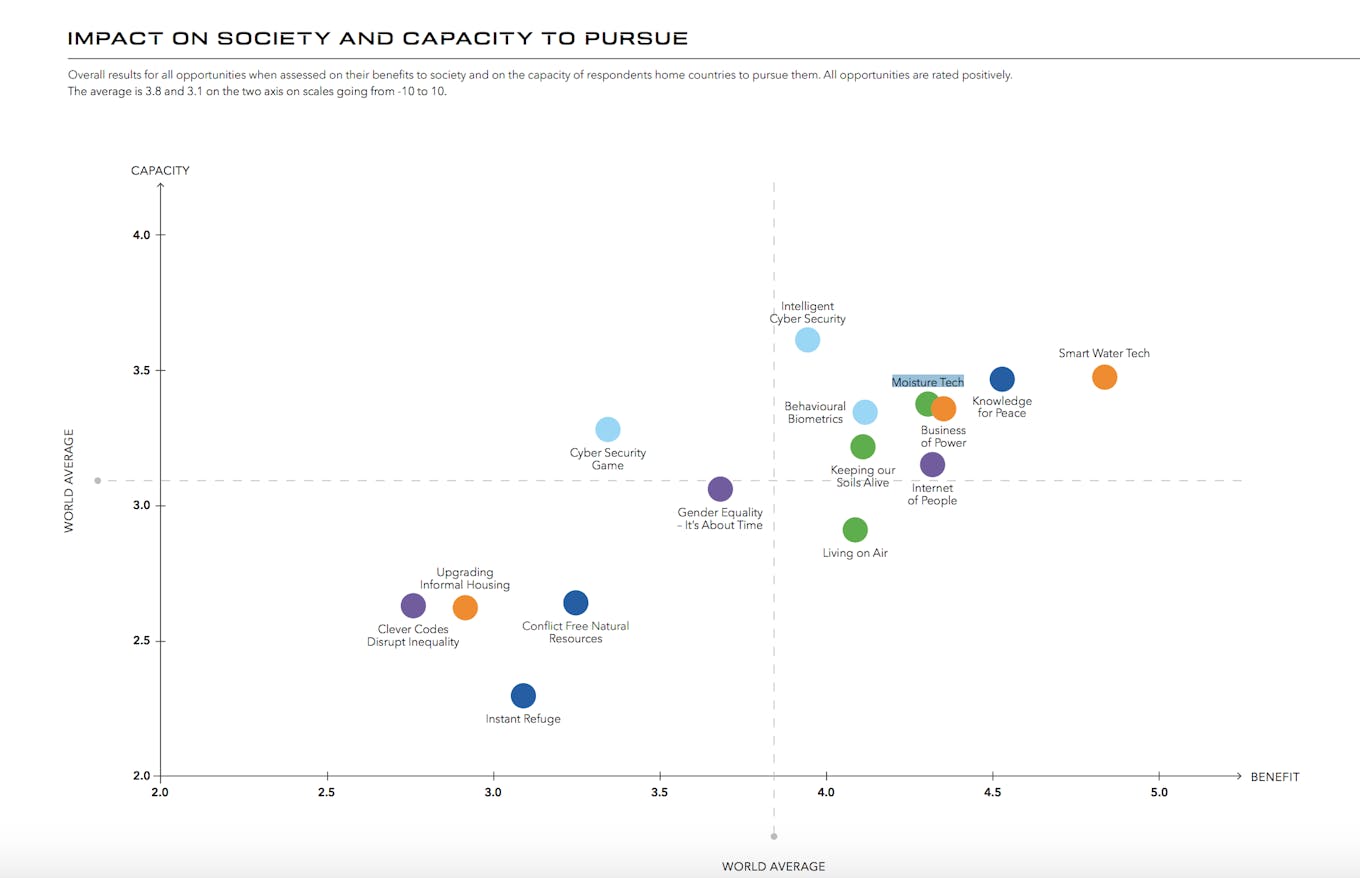

However, when it polled 5,500 business leaders on their willingness to develop more solutions to address soil degradation, the report found a glaring discrepancy between the potential impact of such solutions and the business case for them.

The report found that respondents ranked the three types of solutions to address soil degradation—rehabilitating soil, growing crops in water-scarce areas, and finding ways to grow food without soil—as developments that would benefit society significantly.

Results from a poll of 5,500 business leaders on the perceived impact of developing solutions to various global challenges. Image: Global Opportunities Report 2017

But when it came to willingness to pursue these opportunities, the response was mixed. While regions like India, China, Southeast Asia and Australia were generally keen with 70 per cent or more respondents saying their companies were likely to develop solutions in these areas, about half of the companies in North America and Europe were unwilling or neutral about the prospect, implying that they did not see a business case for doing so.

Thanks to this discrepancy between the potential benefits of developing solutions for soil and its business case, “we have chosen to name the soil opportunities a ‘partnership challenge’”, says Grann. “It is highly unlikely that business alone will pursue the three opportunities.”

“We can expect partnerships to form between business and civil society in the coming years to unlock the full potential for addressing this risk and unlocking the business potential in making our soils fertile again,” he adds.

What healthy soil looks like. Image: NRCS photo, CC BY 2.0

Consumers matter too

But addressing soil degradation isn’t just the job of governments or policymakers, say experts. Consumers can play a role in this too.

FAO’s Niino observes that consumers are often willing to pay a higher price for organically grown or Fair Trade products, because they understand that their money supports positive practices. A similar understanding of the benefits of conservation agriculture would go a long way towards supporting agricultural practices that promote soil health, he says.

Montgomery adds that a brand label or certification system that identifies produce grown in accordance with conservation agriculture principles, “would allow consumers to vote with their dollars”. It would also get agribusinesses which control huge global supply chains to encourage their farmers to use practices that don’t damage the soil in the long run, he says.

For consumers living in countries where it is possible to buy produce directly from growers—at farmers’ markets, for instance—they can also inquire about how farmers grow their crops, and support farmers who use conservation agriculture practices, Montgomery recommends.

Ultimately, soil health should be a “top policy concern and a priority for any farmer who is concerned about the state they want to leave their land in for their children and grandchildren,” Montgomery says.

“The idea that we will run out of soil in 60 years is not a foregone conclusion,” says Montgomery. “The future of the world’s soils depends on the choices that people make for how we farm.”