A Malaysian palm oil producer has become the first company in the world to elect a non-human animal to its board of directors.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Sabah-based grower Mun Kee Ma-Jik Bhd has appointed a Bornean orangutan as a special advisor to the board, effective on 1 April.

Named Aman, which means peace in Malay, the great ape will be deployed to help manage human-animal conflict in areas where the company is expanding plantations within its concession.

The seven year-old primate, who was orphaned as an infant after her parents were lost to forest fires, is known for her calm demeanour and ability to socialise with stressed orangutans, the company’s chief sustainability officer Dr Gurin Woscher, said in a statement.

“Aman will help develop our stakeholder engagement and responsible growth plans and add another dimension to our free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) policy,” said Woscher.

FPIC is a principle companies use to ensure bottom-up participation with local communities and indigenous peoples before developing land. Aman’s hire is the first time FPIC been used to gain consent from non-human animals.

Orangutans have the ability to adopt and pass along learned behaviours, and Woscher said he hoped that Aman could influence her fellow orangutans living within the concession to adopt more passive behaviour.

There have been numerous incidents of orangutans attacking excavators and bulldozers to defend their homes, Woscher said.

Boardroom diversity goes bananas

Woscher said that Aman’s appointment also blazes a trail for boardroom diversity.

“The corporate world has come a long way to improve boardroom diversity — even in Malaysia, where less than 7 per cent of board members are women. But true board diversity goes beyond that of just gender, age or even race,” said Woscher.

He pointed to studies that show that more diverse boards deliver better business results.

“We hope that having an orangutan on the board — which are intelligent creatures not known to destroy their own environment, like us humans — will steer us to greater profitability by helping us to sensitively manage conflict areas,” Woscher said.

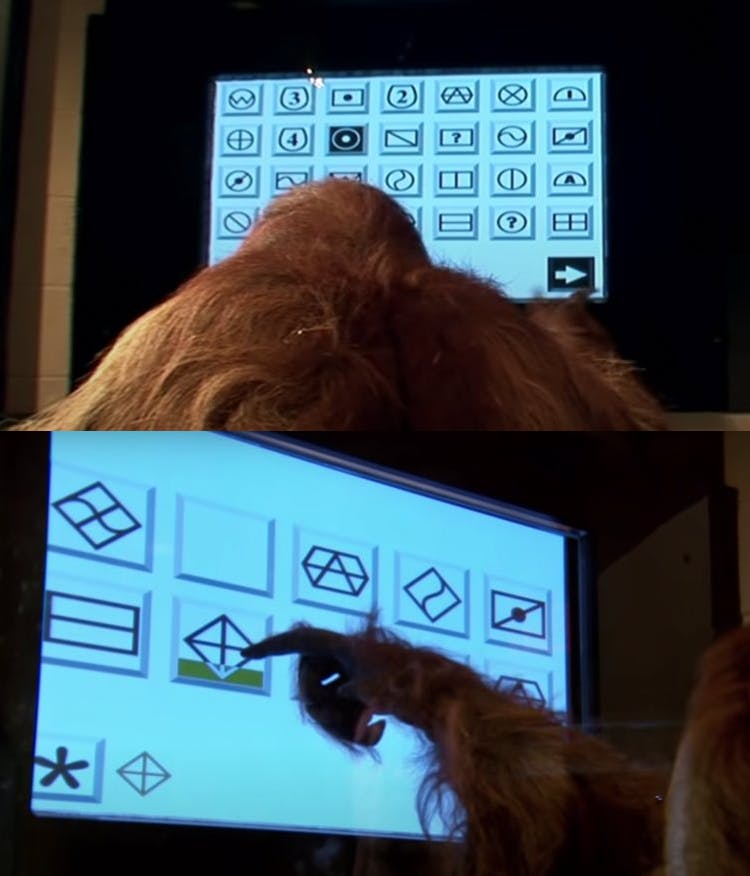

Aman using a touchscreen to get her point across in board meetings. Image: BBC Earth

Aman will share her point of view in board meetings by using a touch screen. Orangutans are able to recognise words, adjectives, and even verbs to communicate with people, research has shown.

Orangutans are also the only non-human mammals capable of communicating about the past. Woscher said it hopes Aman can ‘talk’ to orangutans in the concession to get a sense of their past experiences, and learn more about what the firm can do to make amends for past harms.

Palm oil producers are under growing pressure to not only stop clearing forests, but make up for past activity by reforesting degraded areas. Last year, KPN Plantation, one of Indonesia’s most controversial growers, committed to remediate 38,000 hectares of forest in Papua and West Kalimantan.

Agribusiness Mun Kee Ma-Jik, which has a capacity of 140,000 tonnes of crude palm oil a year produced over 6,000 hectares of plantations, has cleared an estimated 4,000 ha of orangutan habitat over its history.

Aman will be remunerated in bananas, and granted leave on International Orangutan Day on 19 August.

Malaysian Borneo’s orangutan population has fallen by about two-thirds since the 1970s as a result of logging and palm oil cultivation.