This is according to a new study that looks at the benefits for climate and human health of reducing emissions from cookstoves in more than 100 countries worldwide.

The authors, from the University of Colorado and Dalhousie University in Canada, published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Health warning

Over 3 billion people – around two fifths of the world’s population – cook their food on open fires using solid fuels like wood, animal dung, coal and biomass as fuel.

This traditional way of cooking releases methane and CO2, both potent greenhouse gases. Past studies suggest burning wood fuel is responsible for approximately 2 per cent of global CO2 emissions.

Burning solid fuels has huge side effects for public health, too. Poor indoor air quality leads to 4.3 million premature deaths per year, according to the World Health Organisation. Emissions from poorly ventilated residential cookstoves are thought to be responsible for around 370,000-500,000 of those premature adult deaths each year.

“

In 2050, 260,000 deaths of people greater than the age of 30 can be avoided annually through the removal of solid fuel cookstoves.

Forrest Lacey, University of Colorado

The problem the new paper addresses is that while the impacts from cookstoves on human health and the climate are fairly well understood, how far-reaching the benefits of reducing emissions could be remains largely unquantified. Part of the reason for the uncertainty is tiny particles known as aerosols, released alongside greenhouse gases when wood and coal burn.

Aerosol effects

Aerosols tend to have a cooling effect by scattering sunlight and by encouraging clouds to form, preventing the sun’s energy reaching Earth’s surface.

Other aerosols have a warming effect, however. Black carbon, or soot, stays around in the atmosphere for days to weeks, giving rise to its label as a ‘short-lived climate pollutant’, or SLCP.

Aerosols’ short lifespans means they exert their biggest influence locally. This can lead to sharp differences from one region to another, making an assessment of the problem on a global scale tricky, say the authors.

The new study paper takes a fresh approach, using atmospheric and chemical transport models to estimate the wider impacts of phasing out cookstoves in individual countries.

Dr Nick Watts, Executive Director of Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change, who wasn’t involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“The benefits [of reducing cookstove emissions] have been known about for a long time…This study builds on that, giving a more comprehensive overview than we’ve had to date.”

A woman uses a cookstove to make rotis and dahl for breakfast, India. Photo: Karan Singh Rathore/sanjhi.org via Carbon Brief.

Phase-out

The authors of the new paper concentrate on 101 countries worldwide where more than 5 per cent of the population relies on solid fuel for cooking.

The paper uses existing regional emissions inventories to separate the contribution from cooking activities from other sources of greenhouse gas emissions and aerosols, and then models the impact of phasing out these emissions at a national and then a global scale.

According to the study’s results, phasing out traditional cookstoves over the next 20-years could cool global surface temperature by approximately 0.08C by 2050, largely a result of cutting black carbon and other SLCPs.

Towards the second half of the century, we start to feel the effects of cutting CO2 and the cooling effect on global surface temperature grows to 0.12C. The paper explains:

“Short Lived Climate Pollutant impacts dominate the response for the first half of the century, whereas the greenhouse gas impacts, particularly CO2, become increasingly important by 2100.”

This saving may sound small, but is far from insignificant. For context, the average temperature of Earth’s surface has warmed at around 0.12C per decade since the 1950s. Or put another way, the 0.12C that could be shaved off global temperature rise from phasing out cookstoves by mid-century is equivalent to about a decade’s worth of warming at current rates.

Country-by-country

The results show that the effect of cutting emissions on global temperature is bigger for some parts of the world than others.

The biggest climate benefits by 2050 would come from halting cookstove emissions in China, India, and Ethiopia, the study notes. Phasing out emissions in these countries could account for about half the total potential reduction in global temperature, say the authors.

On a per cookstove basis, emissions in Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan likely have a disproportionately large effect on climate, because black carbon is transported to the Arctic where it darkens the snow and causes it to reflect less heat.

The authors hope a targeted approach to phasing out traditional cookstoves, based on the countries they identify, could pay dividends for the climate. Lead author Forrest Lacey, a PhD student at the University of Colorado, tells Carbon Brief.

“The most surprising results were the high per-cookstove impacts in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. These are regions that are not typically targeted for clean cookstove implementation programs.”

The co-benefits to health of cutting emissions is clear, Lacey adds:

“In 2050, 260,000 deaths of people greater than the age of 30 can be avoided annual through the removal of solid fuel cookstoves.”

Better ambient air quality as a result could prevent around 22.5 million premature deaths between 2000 and 2100, the paper explains – approximately the population of Australia.

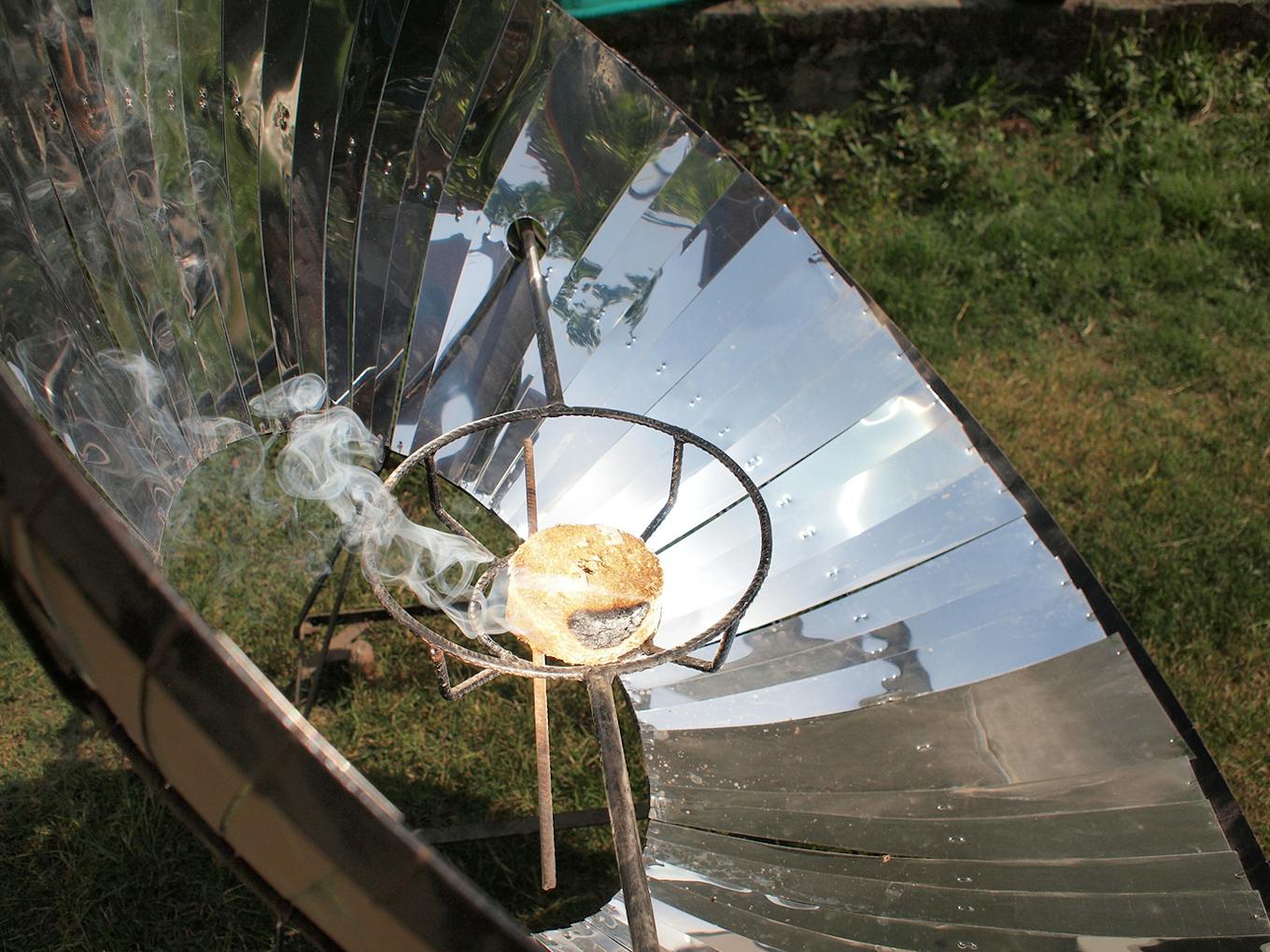

In Kathmandu’s morning sun, a solar cooker lights a fuel briquette. Many non-profit organisations are encoraging the use of solar cookers to reduce air pollution and deforestation. Photo by Rob Goodier/E4C via Carbon Brief.

Access to energy

With solid-fuel cookstoves providing the traditional way of cooking in many parts of the world, what should they be replaced with? There are a number of options, Watts tells Carbon Brief:

“In an ideal world, everyone would have access to a grid supplied by renewable electricity for cooking. But that is a long way off.”

In the absence of that “gold standard”, cookstoves could be run off decentralised solar energy or, failing that, adapted to burn liquid petroleum gas, biogas or ethanol, he explains.

“Clean cookstove” technology has been around for more than a decade. The Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, for example, is working to implement 60 million clean cookstoves by 2017. But deployment has been slow to date for a host of reasons, says Watts:

“The barriers to deployment can be anything from encouraging individual behavioural change to large national infrastructure issues.”

Watts is realistic, suggesting that a 100 per cent removal of wood and coal-burning cookstoves over the next 20 years may not be feasible in many regions. But targeted interventions in places where phasing out traditional cookstoves could have the biggest impact makes sense, he says:

“Sometimes looking at one issue – either health or climate – in isolation hasn’t worked out well. But in this case, it’s a good solution to both. It’s a win-win.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.