Global energy demand from cooling technologies is expected to triple by 2050, but the companies that make air-conditioners and refrigerators are not innovating to rein in the sector’s monster carbon footprint, nor are they promoting their most energy-efficient products, a new report has found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Asian cooling industry giants such as Daikin, Hitachi, Samsung, LG Electronics, Panasonic and Mitsubishi Electric spend on average just 2.2 per cent of sales on research and development (R&D)—well below the 3.5 per cent average for capital goods—and are not investing in finding alternatives to the energy-guzzling vapour compression technology that was invented more than 100 years ago.

These multi-billion dollar companies are investing in innovations that deliver small, incremental emissions reductions and are showing little ambition to reduce the climate impact of their products, the report titled Playing it cool from environmental measurement non-profit CDP found.

This is reflected by the fact that 60 per cent of industry patents filed have been focused on compressor design, and only 5 per cent of innovations are considered transformative—that is, they integrate solutions to significantly cut energy use, such as smart grid and renewable sources.

Just over a-third (35 per cent) of innovations in the cooling sector are deemed evolutionary, and for example lower the global warming potential (GWP) of the refrigerants the sector is notorious for, such as planet-heating hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), the report found.

“

Elon Musk has got his hands full fixing the battery and going to space. But we need someone to break the mould in cooling innovation.

Carole Ferguson, head of investor research, CDP

The sector is lacking a disruptive force to drive innovation, as Tesla has done for the automotive sector, noted the report’s lead author, Carole Ferguson, CDP’s head of investor research.

“Some of the biggest cooling tech firms like LG and Samsung make high-tech products in other sectors, such as smartphones, where innovation is essential to staying competitive,” she said. “But they’re not innovating in cooling, which is a small part of their business.”

This is partly because consumers don’t expect much innovation from cooling technologies, Ferguson explained. “Consumers clamour for the latest mobile phone gimmickry, but are not focused on the efficiency of an air-conditioner.”

No incentive to sell climate-friendly products

The report, published on Wednesday, studied the product portfolios of 18 of the world’s biggest cooling companies, which are either Japanese, Chinese, Korean or American. These firms dominate the market, accounting for 60 per cent of the US$300 billion cooling industry.

The study also found that these companies are promoting and selling some of the least efficient products in their portfolios; those that are just efficient enough to meet energy efficiency standards.

Only seven companies in the study generate more than half of their sales in better regulated markets such as Japan, the European Union and the US, where there are financial incentives for energy efficient products. Most sell their wares in poorly regulated markets such as India, Indonesia and Vietnam, where they are not mandated to sell efficient products—so they don’t market them.

Product efficiency analysis of air conditioning systems in the report revealed that the gap between the minimum efficiency performance standards (MEPS) of the countries these products are sold in, and the best available technology companies have in their product portfolios, is 58 per cent. Across the full range of air-conditioning products, the efficiency gap is 17 per cent on average.

Ferguson said that regulation has not been stringent enough, particularly in developing markets such as India, where demand for air conditioning is projected to grow rapidly, as temperatures and disposable income levels rise.

“Companies have no incentive to sell their most efficient products in those markets,” said Ferguson, noting that in India, even among the most energy-conscious companies, the gap between the efficiency performance standard and their product’s efficiency was 7 per cent.

Cooling companies are also noticeably cool on climate action for such a high impact category. Only four firms have set targets to cut emissions through the value chain: Hitachi and Mitsubishi Electric are targeting an 80 per cent reduction, while Daikin Industries and Electrolux are aiming for net-zero emissions.

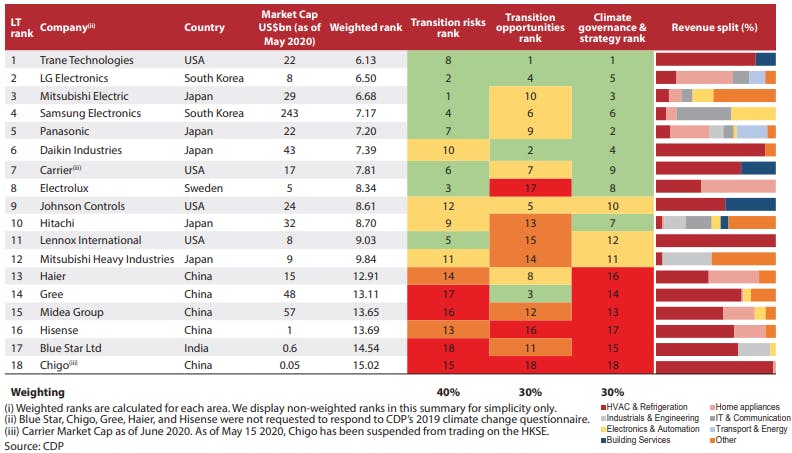

The report ranks US-headquartered Trane Technologies top of a table that grades firms by the efficiency of their products (denoted as “transition risks” in the table below), low-carbon product innovation (“transition opportunities”) and emissions reduction targets (“climate governance”).

Korea’s LG Electronics and Japan’s Mitsubishi Electric are second and third, respectively. Companies from China, including Chigo, Hisense, and Midea, feature at the foot of the table.

A ranking of cooling technology firms by energy efficiency, product innovation and climate action. Image: Playing it cool: Which cooling companies are ready for the low-carbon transition?

The report emerges two years after a study produced by Eco-Business for the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program found that if Southeast Asian countries switched to energy-efficient cooling products, they could reduce energy costs by US$12 billion a year, and reduce emissions equivalent to the annual production of 50 coal-fired power plants.

Few regions are seeing demand for cooling grow as quickly as Southeast Asia, where aircon and refrigeration are projected to account for 40 per cent of the region’s electricity demand by 2040.

Globally, emissions from cooling have tripled since 1990 and are continuing to rise, with space cooling set to become the biggest driver of growth in electricity from buildings over the next 30 years.

Improving cooling efficiency would help achieve 40 per cent of the emissions reductions needed to keep global warming to within the 2-degree Celsius ceiling in line the Paris Agreement, according to the International Energy Agency.