“No bird species has been lost to climate change yet,” said Tris Allinson, a senior conservation scientist at BirdLife International, a wildlife conservation group. “But there is a very real possibility of losing the Great Indian Bustard to poorly planned renewable energy infrastructure.”

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

As India forges ahead with a plan to ramp up the pace of renewable energy deployment, environmentalists are increasingly worried that nature will be collateral damage. The Great Indian Bustard, an ostrich-like bird whose vulnerable population of 100 is losing 10-15 individuals a year to collisions with power lines for new renewables installations, is a potential casualty. At its current rate of decline, the state bird of Rajasthan could be extinct within a decade, and groups like BirdLife International now find themselves at odds with clean energy proponents as they fight to protect precious biodiversity.

Their efforts, however, are paying off. In April last year, India’s Supreme Court ordered all power lines in the area of the Thar Desert to be moved underground to protect the bird, after prolonged appeals from conservationists. The desert, a 200,000 square kilometre expanse of sand, scrub and rock that serves as the bird’s last breeding ground, had been considered a suitably barren location to deploy vast fields of wind and solar. With the court order, energy companies now find themselves in a bind, and are complaining that this would render their renewables projects financially unviable.

“Now no new renewables are being built and the industry has come to a halt, because a sensible location [for wind farms and solar panels] was not chosen in the first place,” Allinson told Eco-Business. “More countries will be faced with similar headaches, and the progress of renewables will slow if proper environmental considerations are not made.”

We are seeing a lot of poorly placed renewables in emerging markets, particularly in Asia where there isn’t strong nature conservation legislation.

Tris Allinson, senior conservation scientist, BirdLife International

The issue of renewable energy projects killing birds is becoming a point of contention. In April this year, a United States wind energy company was ordered to pay $8 million in fines after pleading guilty to killing at least 150 bald and golden eagles at its wind farms in violation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. According to a study by the Wildlife Institute of India, around 100,000 birds die every year in the Thar region as a result of collisions with wind turbine blades and power lines. Large birds are the most vulnerable; birds of prey are particularly prone as they tend to look down for prey — not up or around them — and find it difficult to turn to avoid cables or wind turbine blades before it is too late.

BirdLife International is concerned that over the next 24 to 36 months, the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy in Asia is expected to accelerate five to 10 times faster than the current rate of growth. This could endanger other bird species if projects are not planned with due care, it said.

Bird casualties from renewables infrastructure deployment. Images: BirdLife International

Not all renewables energy is ‘green’

Part of the problem, said Sue Mulhall, global lead of partnerships and biodiversity at BirdLife, is that the renewable energy sector considers itself inherently green, because of its role in combating climate change.

The Global Wind Energy Council, the industry body for the wind sector, did not respond to questions from Eco-Business about where biodiversity conservation figures in its plans to grow the industry ninefold in Asia by 2050. According to industry sources, biodiversity remains low on the list of priorities for wind and solar as the region scrambles to meet climate targets and trade carbon credits.

Abhishek Rawat, senior sustainability manager of Singapore-headquartered regional energy firm Sembcorp, in response to Eco-Business’s queries, said that environmental risk is a key factor for wind and solar deployment in India and elsewhere, and firms need to carry out impact assessments — which include avoiding migratory bird flight paths — before they can secure a development loan from banks. Sembcorp is aiming to quadruple its renewables portfolio by 2025 to meet a 2050 net-zero target.

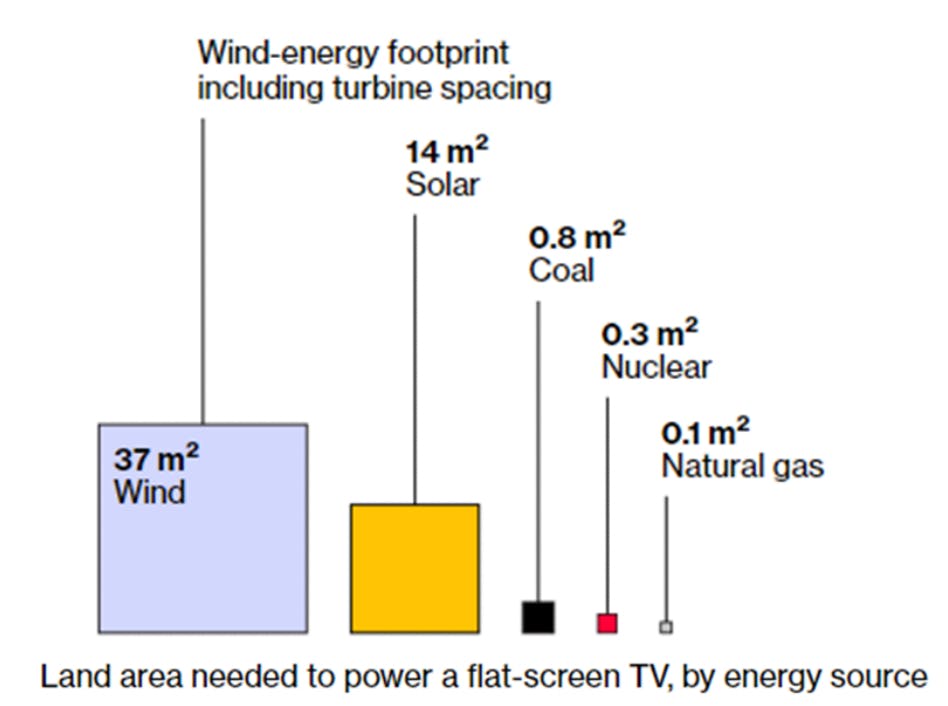

Land area need to power a flat-screen television, by energy type. Sources: van Zolk, John, Behrens, Paul, 2018, The Spatial Extent of Renewable and non-Renewable Power Generation

But there is clearly more work to be done to ensure energy companies follow protocol and avoid the climate fight and biodiversity conservation clashing. Wind farms and solar panels will require millions of hectares of land and sea to meet climate targets, which in turn will require more than double the amount of power lines, BirdLife warned.

“We are seeing a lot of poorly placed renewables in emerging markets, particularly in Asia where there isn’t strong nature conservation legislation. Infrastructure is being put in places considered ‘empty’. But these are often high biodiversity areas,” said Allinson.

If renewable energy projects were placed purely where it is windiest and sunniest, more than 11 million hectares of natural lands, including over 3 million ha of biodiverse habitat, could be lost, according to BirdLife. This habitat loss would not only put 15,000 threatened species at risk of extinction, but would release over 400 million tonnes of stored carbon.

But true sustainable energy development, which does not harm biodiversity while curbing emissions, is possible. According to a 2019 study by The Nature Conservancy and others, India has 12 times the area of degraded, low-impact land it needs to meet its target to deploy 175 gigawatts (GW) of renewables this year.

Nudging developers away from sensitive areas

“BirdLife is 100 per cent supportive of a rapid, wholesale transition to renewable — it should be done faster. We are saying that renewables can be deployed even faster if the planning is done right,” said Allinson, who sits on the Convention of Migratory Species’ energy taskforce, which is working with energy stakeholders to establish best practice in wildlife-friendly renewable energy deployment.

BirdLife has been working with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to develop a tool to prevent renewables development from pushing more species into the same corner as the Great Indian Bustard, whose fate Allinson said is now “inevitable and imminent”.

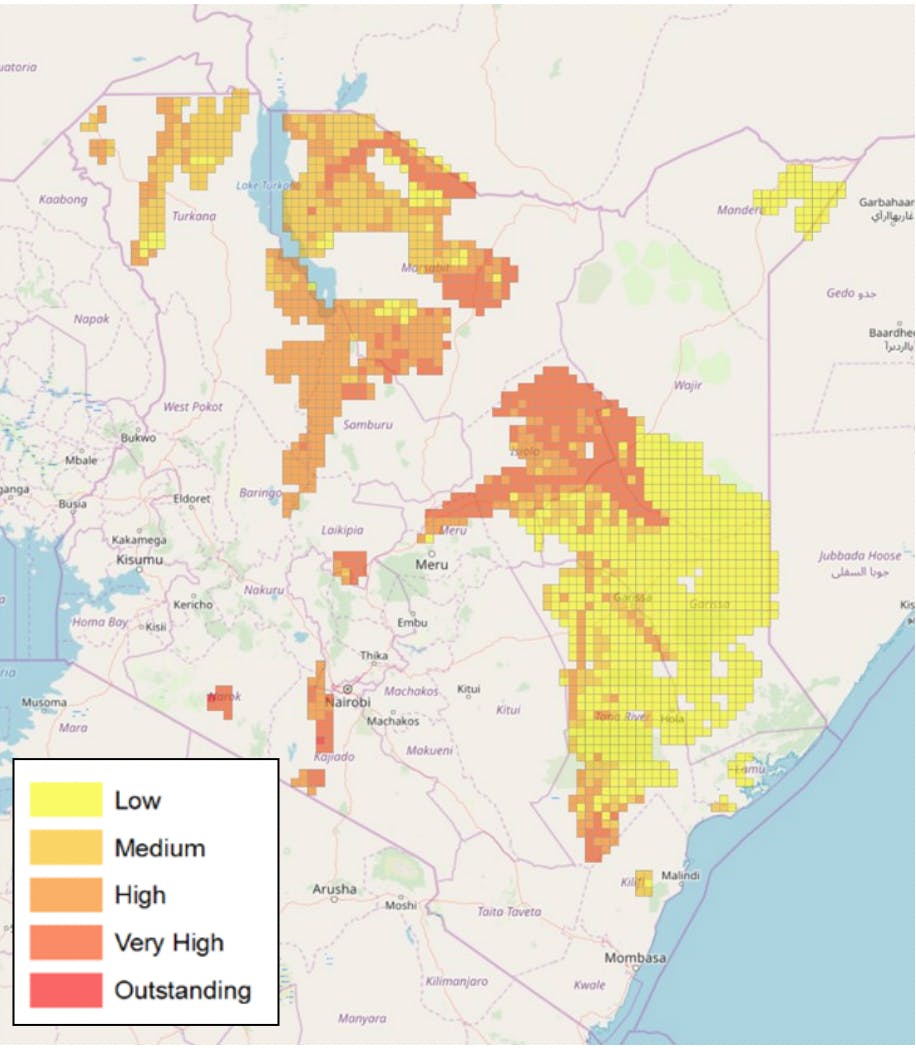

This map shows those areas in Kenya that are commercially suitable for wind energy colour-coded according to their threats to birds and bats. Source: BirdLife International

Launched at the ADB-organised Asia Clean Energy Forum on Thursday, Avistep is an online mapping tool that shows developers of solar, off- and onshore wind projects where areas of low, moderate and high risk to birds are on land and sea, to a resolution of five square kilometres.

The “sensitivity mapping” tool — which is currently in Beta mode with a full roll-out slated for July — is so-called because ADB believes avians (birds) should be an early step in considering where to put renewables farms.

Avistep has been developed for India, Nepal, Vietnam, and Thailand first, because these are countries with particularly high biodiversity, weak conservation laws, and big plans for renewables deployment. The idea is to start with these countries, and roll the tool out in other emerging markets where the energy transition is gathering pace.

Duncan Lang, an ornithologist who consulted on the biggest renewables farm in Europe before joining ADB as senior environmental specialist in 2017, acknowledged that there may be resistance from developers advised to stay away from particularly sunny or windy, biodiverse areas. But the idea is to help, not hinder, clean energy development in Asia, he said.

“People who do EIAs [environmental impact assessments] are often viewed as the annoying people who ruin projects for engineers. But we are not saying developers cannot execute a project — they can. We are just asking them to develop areas with lower risk to wildlife,” Lang tells Eco-Business.

Nudging developers away from sensitive areas will enable them to meet ADB’s lending criteria — ADB introduced a “nature-positive” investment agenda last year — and will prepare them for regulations that penalise nature-harming renewable energy projects, Lang says.

The European Union is soon to release a new directive for the renewable energy sector that puts sensitively mapping at the forefront, as the region scrambles to ramp up alternatives to Russian fossil fuels. Asia may follow with a similar policy path as biodiversity creeps up the global agenda.

Recognition of nature’s role in climate change mitigation and adaptation is growing, says Lang, with biodiversity protection a major theme at the COP26 climate talks for the first time last year, and the delayed COP15 with its focus on nature expected to push for more legislation and capital allocation for nature protection, particularly in developing countries.

Critics of efforts to make renewables more wildlife-friendly say that it misses the bigger picture — that fossil fuels cause more harm to nature than solar or wind farms. But Lang said there is still no justification for renewables projects that compromise nature, particularly in Asia. There is so much degraded agricultural land in Asia that conflicts with conservation interests can easily be avoided, he said.