Consumption of meat and dairy products in many countries has risen beyond healthy levels, the report says, and emissions from rearing livestock mean growing meat demand will make it harder to keep global temperature rise below 2C.

Political leaders are “afraid of telling people what to eat”, says the authors, but the findings suggest the public may be less averse to changing their diets than governments fear.

Livestock emissions

As you can see in the chart below, consumption of meat and dairy products generally increases as a country’s national income rises. While this growth flattens off as earnings climb further, meat eating in many developed countries has plateaued at excessive levels, the report says.

The dotted line shows a healthy level of meat in our diets. On average, in Europe we eat around twice as much as we should, while in the US it’s three times.

This is bad for our waistlines and the climate, the report says.

Meat consumption per person (in kg per year) plotted against national average incomes (in US dollars per year). Includes intake of beef, pork, chicken and eggs. Dotted line shows healthy level. Source: Chatham House (2015).

Our appetite for meat is a major driver of climate change, says lead author Laura Wellesley, a research associate at Chatham House. She told a press conference: “Globally, the livestock sector accounts for 15 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions – that’s equivalent to all exhaust emissions from every vehicle on the planet.”

Rearing livestock produces emissions directly from animals, from digestion and manure, and from transporting animals and producing their feed. Greenhouse gases are also released when forests are cleared to make way for pasture or for cropland in order to grow animal feed.

Global demand for meat is expected to increase by 76 per cent by the middle of this century as both population and incomes rise, Wellesley says, which means emissions are set to rise as well.

Research last year by Chatham House found that without keeping a lid on rising meat and dairy consumption, keeping global temperature rise to 2C above pre-industrial levels was “off the table”. The new report asks how to go about bringing global diets in line with climate emissions targets.

Cycle of inertia

The issue of how to address meat and dairy consumption has been “trapped in a cycle of inertia”, the report says. Governments have shied away from promoting sustainable diets in fear of a backlash from the public and food industry, while the lack of action means public awareness of the climate impact of meat and dairy is low.

“

The assumption that interventions like this are too politically sensitive and too practically difficult to implement is unjustified. Our focus groups pointed to a public that expect governments to lead, that expect governments to take action on issues that are in the public interest.

Laura Wellesley, research associate at Chatham House

The researchers conducted discussion groups with members of the public in Brazil, China, the US and the UK to explore attitudes to meat and dairy consumption.

The results showed that the public wanted guidance from the government on how much meat they should eat, with participants of the focus groups saying they were unlikely to change their eating habits without it. The report concludes: Government inaction signals to [the general public] that the issue is unimportant or undeserving of concern.

The findings also suggest that the public may be less reluctant to being asked to cut their meat intake than governments fear. Wellesley explains: “The assumption that interventions like this are too politically sensitive and too practically difficult to implement is unjustified. Our focus groups pointed to a public that expect governments to lead, that expect governments to take action on issues that are in the public interest.”

This action could include “nudges” towards more sustainable food choices by improving awareness, food labelling and availability of alternative options. But the most effective method of changing eating behaviour is likely to be taxation, the findings suggest.

The Chatham House report doesn’t look into possible tax levels, but research published in the British Medical Journal in 2013 found that taxing the carbon emissions from beef production at £2.72 per tonne of CO2eq for every 100g of beef would result in a £1.76 increase per kilo. This in turn could lead to a 14 per cent reduction in consumption.

Although there would be some initial opposition to adding taxes to meat and dairy, public acceptance would come in the long-term, Wellesley says: “Our research also indicates that any backlash to unpopular policies would likely be short-lived.”

The public are more likely to accept a tax if they can see the revenues are being redistributed towards other foods, the researchers add.

An opportunity, not an impossibility

So, how much of a difference to global emissions could healthier diets make? Wellesley explains: A global shift to healthy diets, which for most would mean a reduction of meat consumption – a significant reduction in meat consumption – could bring a quarter of the emissions reductions needed [by 2050] to bring us back online for the 2C target.

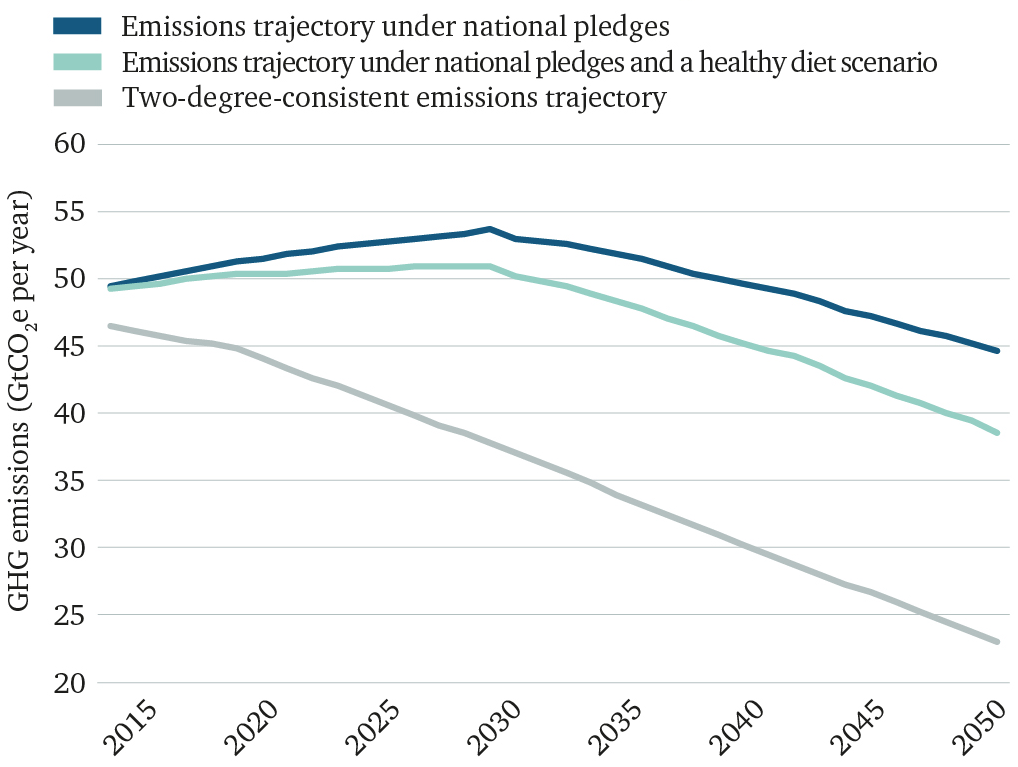

You can see this in the chart from the report below. The dark blue line is the future emissions path based on the existing national pledges for cutting greenhouse gases emissions, while the pale blue line shows the reduction if the world shifted to the healthy levels of meat and dairy consumption. The grey line shows the path necessary for 2C.

Emissions reduction scenarios to 2050. Shows trajectory under current national pledges (dark blue line), with the additional of global healthy diets (pale blue), and for 2C. Source: Chatham House (2015).

But you needn’t rush out to stock up on sausages before they disappear from supermarket shelves, says Wellesley: “We’re not in any way advising or advocating for global vegetarianism. It doesn’t need that. You can see a massive change and huge emissions reductions from just converging around healthy levels and moderating our intake.”

For example, a study published in Nature Climate Change last year suggested that a global diet of no more than 24g of red meat a day, and no more than 85g of chicken, would save six billion tonnes of CO2e by 2050. For reference, the beef burger in a standard McDonalds hamburger weighs in at 33g.

Cutting back on meat and dairy has a dual benefit of improving global health as well as helping to limit climate change. This makes a “compelling case” for governments to encourage the public to shift their diets, Wellesley concludes: The key message here is that governments should see dietary change not as impossibility, but as an opportunity.