In 2016, Ho Xiang Tian co-founded the whimsically-named environmental group LepakInSG – “Lepak” means to go somewhere to relax, in Malay and “Singlish” – with the original intention of producing a simple online calendar for environmental events in Singapore.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“At that time no one in Singapore was interested in environmental issues. By choosing a fun, informal name, we thought we could trick a few people into clicking on our website,” said Ho, who started the group with Nor Lastrina Hamid and Gracie Low when he was in his final year at Singapore Polytechnic.

But after three days of copy and pasting events into a Google calendar, the trio got bored. Instead, they decided to initiate green-themed events, workshops and public education campaigns. A year later, LepakInSG had developed into a fully fledged environmental advocacy group.

Eight years on, Ho is one of Singapore’s most prominent young environmental activists, agitating for his country to do its fair share to slow global warming, curb resource consumption – the city-state’s ecological footprint exceeds its biocapacity by as much as 10,400 per cent, which is the highest for any nation – and reduce biodiversity loss as it urbanises and its wild spaces dwindle.

I would like to see more transparency. I would also like to see a Singapore that is less business friendly at the expense of the environment.

Ho Xiang Tian, co-founder, LepakInSG

Ho Xiang Tian’s bio on LepakInSG’s website illustrates his informal approach to activism. Image: LepakInSG.wordpress.com

Ho’s relaxed approach to campaigning – he is known in sustainability circles as the guy who always wears slippers, even to official government events – has given him and his team a playful, non-confrontational vibe in a politically conservative country that can be a difficult place for activists who publicly criticise government policy and rally for systemic change.

Though understated, Ho has not shied from putting his head above the parapet to push for more progressive environmental policies in Singapore. In a speech at a climate rally in September last year, Ho railed against the packaging industry for blocking polluter pays laws, Big Oil for not paying taxes, and the government for doing the “bare minimum” to respond to the climate emergency.

Ho lives by a principle he campaigns for – to preserve resources. The non-profit he runs has spent nothing on campaigns, operations or anything else since its founding in 2016, he said.

“We are cheapskates, I guess… We founded LepakInSG when we were students. It was easier to find people who could give me what I needed for free rather than find the money to get stuff. Over time it became a matter of principle to spend nothing.”

The group runs on the “blood, sweat and tears” of its 20 volunteers. Juggling student and work life – Ho’s day job is as a research assistant at Singapore Management University, working under prominent climate scientist Winston Chow – “Lepak-ers” double or triple hat, working on issues such as land use, food security, deciphering international negotiations, and networking to bridge the divide between Singapore’s nature and sustainability communities (“they don’t really talk, so we try to bring them together,” said Ho).

This year has been a big year for the 28-year-old Singaporean, whose team successfully pushed back against proposed fish farms in the Southern Islands they worried would ruin coral reefs, and took the Singapore Food Agency to task over discrepancies in its food import data. In this interview, Ho talks about the future Singapore he most wants to see.

In your speech at last year’s SG Climate Rally, you said that the government is doing the bare minimum to tackle climate change. What more can Singapore do?

Singapore has set a target of reaching net zero by 2050, which is the target scientists have set to limit global warming to no more than 1.5°C. This is a reasonable target, but it is the bare minimum that we can do to tackle climate change.

Countries that can afford to get to net zero earlier should get there earlier. This would help countries that are struggling to reach net zero by giving them a buffer to hit the 2050 target a bit later.

The narrative we always hear from the government is that Singapore is small, and only emits 0.1 per cent of global carbon emissions. But the climate crisis is not just about us. Singapore has the resources and the potential to help the region transition to net zero much faster.

How can it do that?

One avenue is through capacity building programmes, which Singapore is already doing for some countries. But these programmes should not be just about setting a net-zero target. We need to help countries get to net zero faster with solutions to transition from fossil fuels, prepare power grids for renewables, move away from coal – and especially not let companies and banks in Singapore continue to fund fossil fuel projects in our neighbouring countries.

Similarly, Singapore should seek to eliminate its role in deforestation and the destruction of carbon sinks in the region. If a company is headquartered in Singapore, and they are deforesting in Borneo, you cannot say that that is a problem for the Indonesian government to take care of, because you have no jurisdiction. The line of responsibility does not need to be so clearly drawn. If we have the means and the resources to help other countries, we should.

Ho and Winston Chow (right), professor of urban climate and Lee Kong Chian research fellow at Singapore Management University, at the Eco-Business Sustainability Leadership A-List in January. Image: Roy Ng / Eco-Business

Tell us more about a key thrust of your speech at SG Climate Rally, in which you suggested that industry players have had an unhealthy influence over government policy, particularly regarding rules to reduce plastic consumption and the carbon tax.

The point I was trying to make was that the industry cannot be trusted to have their own voluntary agreements – for anything. Industry will promise us something, set a target, and put in the least possible amount of effort to reach that target – which delays action to address the issue. One example of this is the carbon tax in Singapore. It was initially going to be S$10 (US$7.44) to S$20 (US$14.88) dollars per tonne of greenhouse gas emissions. But it somehow dropped to S$5 (US$3.72) [when the government introduced it]. Industry was trying to drag its feet. And it worked.

[Background note: The Singapore government announced plans to implement a carbon tax of between S$10 and S20 per tonne of emissions from 2019 at the 2017 Budget and started a six-week public consultation. It introduced the carbon tax at S$5 per tonne of emissions in November 2022. The tax rate will progressively increase to S$25 per tonne in 2024 and S$45 per tonne in 2026 and beyond.]

How would you want the relationship between the government and businesses to change?

I would like to see more transparency. I would also like to see a Singapore that is less business friendly at the expense of the environment – because that seems to be what is happening now. But even so, I believe that the government is starting to acknowledge that we can no longer carry on like we have done historically.

I’ve heard from a senior source at the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment that Singapore has plans to ultimately phase out fossil fuels from its refineries [Singapore is one of the world’s largest oil refining hubs]. The government does recognise that while fossil fuels helped us when we were small and weak, now that our economy has matured, it’s time to move on. We cannot be stuck refining petrochemicals forever.

Much has been made of the loss of Singapore’s secondary forests to make way for residential housing and the impact this could have on biodiversity and urban heating. What’s your view on this?

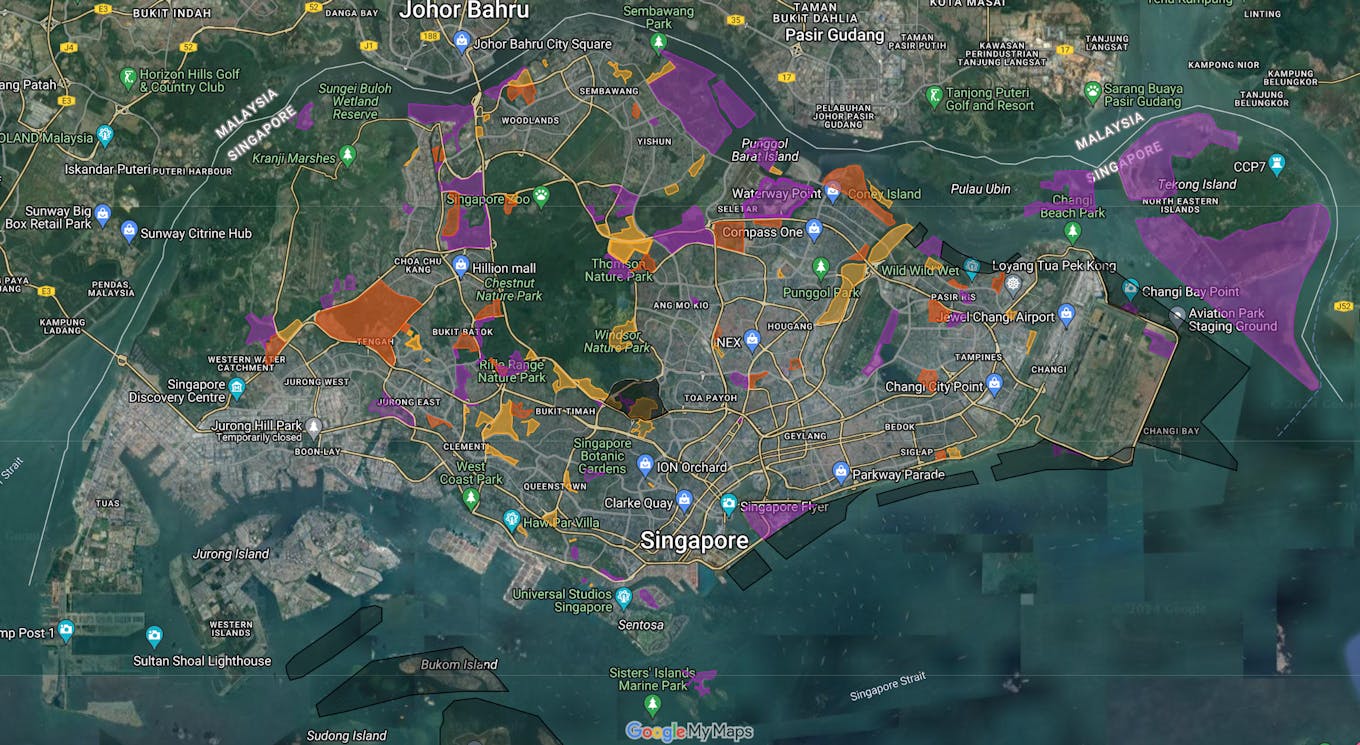

The National Parks Board generally does a good job of maintaining our nature reserves. But forest patches that are not part of a nature park or a nature reserve are at risk. My team has mapped these forest patches as part of the project Our Wild Spaces. Based on the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) masterplan [which maps out areas of the city that will be developed over the next 10 to 15 years), we could be losing a lot of our remaining secondary forest patches.

A map of wild spaces under threat from development in Singapore. Purple areas indicate reserve sites, where future plans have not been determined. Yellow indicates forest not cleared, but earmarked for residential or business development. Red indicated forests cleared or partially cleared for residential or business use. Image: LepakInSG / Our Wild Spaces

We need to think about how to make better use of space that is already developed, so we can leave our wild spaces untouched for as long as possible. Many of our golf courses’ leases expire by 2030. [Singapore’s 17 golf courses cover two per cent of the country’s land area.] The government is planning to take back some of those leases for development, which is a good thing.

We also need to optimise built-up areas. URA has done a pretty good job of intensifying land use, for instance Our Tampines Hub, which combines a community centre, shopping centre, sports hall, hawker centre and library in one place. Moving forward, we should be looking at which land parcels we can make better use of, rather than developing green field sites.

I have a radical idea. Instead of flattening forests to make way for public housing, take away landed properties and give whoever’s living in them a penthouse apartment in a public housing block.

“

Stop clearing Singapore’s forests for public housing, use landed property and golf courses instead.

Describe the Singapore of the future you most want to see.

A Singapore with a built environment more in harmony with the climate. Rather than just steel and concrete boxes pumped with airconditioning, there would be traditional buildings inspired by vernacular architecture that allow passive cooling.

A Singapore with thriving natural ecosystems. What we have now is pretty good, but I’d like to see better connectivity between forest patches, and secondary forests given the time and space to grow so they can support more wildlife, even wildlife from Malaysia escaping deforestation [the southern part of neighbouring Johor has been extensively deforested in recent years to make way for development]. We could see more tapirs in Punggol [A rare Malayan tapir was spotting running along Punggol park connector in September 2023; it was only the third sighting of the endangered mammals in Singapore, which are typically found in the rainforests of Malaysia, since 1986]!

A Singapore with fewer cars on the roads – and less space taken up by roads. More people would use public transport, and use a public transport system that is even better than what we have now – even though I acknowledge that we already have a world-class public transport system.

A more walkable city. At certain times of the day, from 11am to 4pm, it is almost impossible to walk around the city. If there was more shading along the roads and paths – and natural shading rather than sheltered walkways – Singapore would be much more walkable and liveable.

And a Singapore that is a genuine climate action leader. Our climate target would be brought forward, perhaps to 2030. We would achieve net zero, and be on the path to carbon negativity. With the resources we have, this is not an unrealistic ambition.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Ho Xiang Tian was one of 10 young sustainability leaders selected for the Eco-Business Youth A-List 2023. Read our stories with the other winners here.