Atomic power could contribute to about a tenth of Singapore’s 2050 energy needs, if the Covid-19 pandemic stretches on, clean energy development slows and countries shun global cooperation, according to a report released by Singapore’s energy regulators.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

It recommended that the country establish “necessary enablers” such as regulations, resources and skilled manpower to quickly adopt nuclear power if needed.

“Building capabilities in advance will enable Singapore to adopt promising technologies quickly when they become viable,” the report said.

The 56-page document, penned with industry players and academics, laid out three 2050 scenarios Singapore could find itself in. Each scenario explores how the country’s energy mix could reach net-zero emissions.

It comes on the heels of Singapore pledging to hit net-zero emissions by around mid-century.

Two upcoming nuclear power technologies were highlighted – small modular reactors, which are faster to build than the current crop of bulky plants, and nuclear fusion, which produces energy by ramming atoms together instead of splitting them.

One small modular unit is already operating in Russia. A slew of nuclear fusion tests have been conducted in recent years, though commercial viability could be decades away.

Singapore has had a nuclear research programme running since 2013. The government had stated in 2012 that it would not pursue nuclear power due to safety concerns, following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, when an earthquake and tsunami flooded reactors, forcing 150,000 people to evacuate.

Earlier this year, the European Union recently included nuclear power projects in its green finance guide. Analysts said the move could be copied by Southeast Asia, where several countries are also tinkering with nuclear ambitions.

The Philippines announced earlier this month that it intends to use nuclear energy to help phase out coal. It is considering switching on its Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, that was constructed in 1976 but has never been used.

Proponents of nuclear power say the energy source can replace fossil fuels to provide a steady flow of low-carbon electricity – something wind and sunlight struggle to achieve. Critics fear the lasting impact of both disasters and nuclear waste, a permanent solution for which largely does not exist.

Peter Godfrey, managing director for Asia Pacific at British non-profit Energy Institute, believes that offshore or underground nuclear power plants could be a possibility for Singapore. Such ideas were floated in Singapore years ago.

However, Godfrey added the island-state will likely hold off until nuclear power becomes more mainstream.

“I think Singapore will wait for Europe, it’ll wait for a lot of other people to get into the nuclear game again, before they jump into it,” he said.

Three 2050 scenarios

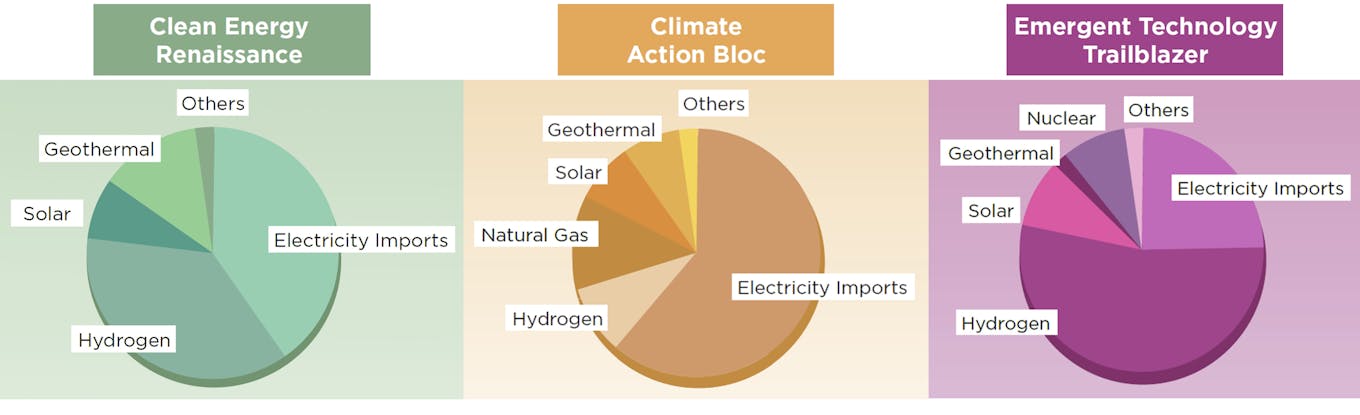

Singapore’s net-zero energy mix in 2050, corresponding to different scenarios, with different levels of global cooperation and clean energy development. Image: EMA.

The report concedes that huge uncertainties remain in the development of clean energy technologies, and if the world can rally around climate action.

The first of three scenarios presented in the report postulates high global cooperation and the rapid development of clean energy technology. Singapore would get 40 per cent of its electricity each from energy imports and hydrogen fuel.

Low-carbon ‘green’ hydrogen, produced with renewable energy, costs US$3 to US$7.50 per kilogramme today, several times higher than the cost of natural gas. Costs are expected to drop in the coming years with better technology and economies of scale.

In the second scenario, a protracted Covid-19 pandemic slows the development of clean energy technology but fosters greater international cooperation. Singapore is able to scale up clean energy imports, to cover 60 per cent of its supply mix. Hydrogen only makes up a tenth of the pie, while natural gas, a fossil fuel, will still feature in energy supply. Carbon credits are used to offset the emissions.

The third scenario paints a picture of global isolationism and slow technical progress on clean energy. Hydrogen makes up over half of total energy needs, while imports cover just under a quarter. Nuclear energy is used in this scenario.

All three scenarios assume geothermal energy from the earth’s crust can be harnessed in Singapore. The country currently does not use geothermal energy but is studying the option, with results expected at the end of the year.

Neighbouring Indonesia is home to 40 per cent of the world’s geothermal resources. The government has identified more than 300 sites with an estimated 24 gigawatts in geothermal energy reserves, the world’s largest. Efforts have been waylaid due to policy uncertainty and pricing regimes making projects less viable.

Apart from studying nuclear energy, the report recommends adopting more energy storage and smart grid technology to facilitate greater adoption of intermittent solar energy.

Singapore has built solar panels on rooftops and on floating structures in water reservoirs, although total energy contribution will only hit about 4 per cent by 2030, due to the lack of extensive open spaces and regular cloud cover.

The report also calls for continued efforts in importing energy, as well as developing carbon capture and hydrogen capabilities.

The city state is looking to fulfil 30 per cent of its energy needs from low-carbon energy imports by 2035, with a call for cross-border project tenders ending next week. However, Malaysia stated in October last year that it will not allow renewable energy to be exported to Singapore.

A US$22 billion project involving 12,000 hectares of solar panels and 3,800 kilometre of cabling running from Darwin, Australia to Singapore is in the pipeline, and could help break the city states’s dependence on natural gas and meet up to 15 per cent of the city-state’s electricity needs.

Singapore has also pumped S$55 million (US$40.5 million) into research on hydrogen and carbon capture.

Singapore’s energy sector contributes to 40 per cent of national greenhouse gas emissions, as it is powered almost entirely by natural gas. It is a key sector covered by the country’s carbon tax, which may rise to S$80 (US$58) per tonne of emissions by 2030.

“The energy transition will require a clear-minded weighing of the trade-offs across energy security, energy affordability, and environmental sustainability,” said Richard Lim, chairman of Singapore’s Energy Market Authority.

“Singapore needs to manage its energy strategy pretty carefully,” Godfrey said. “Energy-related businesses represent a large part of the economy, and being a small island with limited resources, how the energy world plays out has a significant impact.”

Godfrey added the report could have done better by including the use of low-carbon fuels outside power generation in its scenario planning. For example, hydrogen fuel is being trialled as a replacement for natural gas in heating, and gasoline in transport.