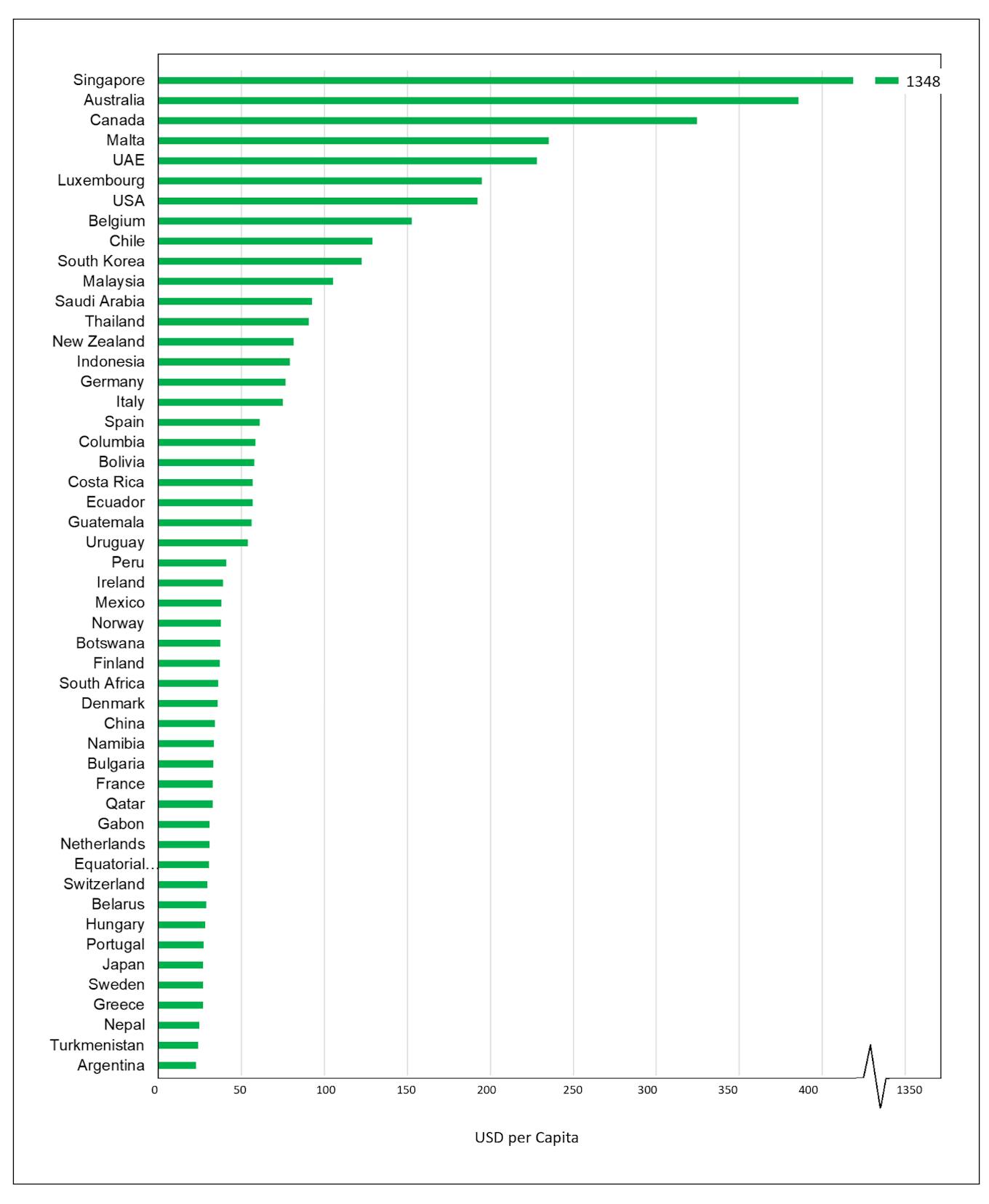

People in Singapore spend the most on bottled water globally, splashing out on average over US$1,300 per head a year for their refreshments, a United Nations study showed.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The money was used in 2021 to buy over 1,100 litres of water per person, the study said, in a review of the global bottled water industry and its impacts on societies and the environment.

Australia ranked second, at about 500 litres and US$386 per head. This is despite drinking from the tap being considered generally safe in both Singapore and Australia.

Globally, people are spending US$270 billion dollars a year on bottled water, when under half of that sum could ensure clean tap water access for hundreds of millions of people for years, the report found. It said the figures represent “a global case of extreme social injustice”.

The report by the United Nations University, the intergovernmental group’s think tank, comes as the world remains off track in ensuring universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030 – a sustainable development goal adopted by countries worldwide in 2015.

Spending per capita on bottled water in 2021. Image: United Nations University. [Click to expand]

Wealthy countries top the list of big spenders. After Singapore and Australia are countries such as Canada, Malta and the United Arab Emirates, based on per capita bottled water sales figures that the UN University authors acquired commercially from a market research firm.

Half of the world’s bottled water revenue comes from Asia Pacific, which also houses populous nations like China, India and Indonesia. The North American market contributes another 30 per cent.

Residents of high-income countries could be drawn to bottled water as a luxury good that is healthier and better tasting, the study said. Manufacturers also target their advertising at groups such as pregnant women, children and sports-minded people to boost sales.

In response to queries, Australia’s Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) said it knows Australians consume large volumes of bottled water, but said there is “good and growing” plastic bottle recovery and recycling infrastructure in the country.

The department spokesperson pointed to a multi-million dollar recycling fund launched in 2020 supporting projects that are expected to process over 290,000 tonnes of plastic a year, including polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common material for drink bottles. Kerbside recycling will be available across Australia by end-2023, the spokesperson said.

In the Global South, bottled water could be the safer alternative to unreliable and unsanitary tap water caused by corruption and chronic underinvestment, the UN University report said.

However, there is “no justification to contrapose bottled water and public drinking water supply sources on the basis of quality”, the report said, pointing to documented cases of contamination from both sources globally.

It added that governments should work on changing consumer attitudes to bottled water, and improve on public water quality standards and regulations. Policymakers should also highlight the possible contamination of packaged water, it said.

‘Hardly compatible’ with human right to water

Based on open-source data, the UN University researchers estimated that close to 600 billion polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottles were discarded in 2021, resulting in over 25 million tonnes of PET waste – more than double the 12 million tonnes produced in 2000.

They noted that plastic recycling rates remain low globally, and that alternative plant-based or biodegradable materials remain costly.

Dr Zeineb Bouhlel, research associate at the UN University’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health, said that governments could regulate plastic production, improve recycling and channel research to plastic alternatives.

Drawing water from rivers and underground aquifers for bottling could also cause “significant” local impacts, despite the total volume being small in absolute terms globally, the study said, referencing past research into water depletion involving bottled water companies such as Coca-Cola and Nestle.

It added that the commercial nature of bottled water trade makes it “hardly compatible” with the human right to water. As it stands, the industry is projected to almost double in size to US$500 billion between 2025 and 2030.

The expansion of bottled water markets is slowing down progress towards the target by “distracting attention and resources from accelerated public water supply systems development”, the report said.

Access to drinking water has improved from 62 per cent globally in 2000 to 74 per cent in 2020, according to the World Health Organisation. But the gap means that two billion people are still left out, and no region in the world is on track to universal water access by 2030, the UN University report noted.

The high sales margins of bottled water provides room for more taxation to reduce inequalities, the report said. Bottled water firms can also contribute to sustainable development through tie-ups with the public sector and investing in the water infrastructure of low and middle-income countries, it added.

The study identified PepsiCo, Coca Cola, Nestle, Danone and Primo Water as the five largest bottled water firms by revenue. They share a quarter of the global sales income between them.

A Danone spokesperson said figures concerning the Évian-les-Bains region in France is incorrect. The report said Danone draws up to 10 million litres of water a day from the area. The spokesperson said the firm works with local comunities, follows regulations, does frequent quality tests for its products and works to keep packaging out of nature.

A Nestlé spokesperson pointed Eco-Business to its initiatives listed on its website, such as employing water-saving practices, engaging in reforestation and restoration projects and using renewable energy in manufacturing.

Report co-author Zeineb said that further research is needed on topics such as bottled water’s impact on groundwater, good government regulations, and where bottled water contributes to improving water access.