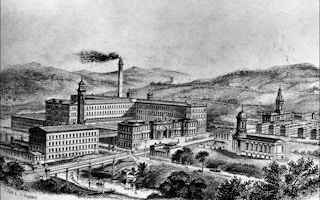

Scientists have identified a human-induced cause of climate change. But this time it’s not carbon dioxide that’s the problem − it’s the factory and power station chimney pollutants that began to darken the skies during the industrial revolution.

Analysis of stalagmite samples taken from a cave in Belize, Central America, has revealed that aerosol emissions have led to a reduction of rainfall in the northern tropics during the 20th century.

In effect, the report in Nature Geoscience by lead author Harriet Ridley, of the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Durham, UK, and international research colleagues invokes the first atmospheric crisis.

Acid rain

Before global warming because of greenhouse gases, and before ozone destruction caused by uncontrolled releases of chlorofluorocarbons, governments and environmentalists alike were concerned about a phenomenon known as acid rain.

So much sulphur and other industrial pollutants entered the atmosphere that raindrops became deliveries of very dilute sulphuric and nitric acid.

“

Although warming due to man-made carbon dioxide emissions has been of global importance, the shifting of rain belts due to aerosol emissions is locally critical, as many regions of the world depend on this seasonal rainfall for agriculture.

Harriet Ridley, scientist, Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Durham

The damage to limestone buildings was visible everywhere, and there were concerns – much more difficult to establish – that acid rain was harming the northern European forests.

But even if the massive sulphate discharges of an industrialising world did not seriously damage vegetation, they certainly took a toll on urban human life in terms of respiratory diseases.

Clean-air legislation has reduced the hazard in Europe and North America, but it seems that sulphate aerosols have left their mark.

The Durham scientists reconstructed tropic rainfall patterns for the last 450 years from the analysis of stalagmite samples taken from a cave in Belize.

The pattern of precipitation revealed a substantial drying trend from 1850 onwards, and this coincided with a steady rise in sulphate aerosol pollution following the explosion of fossil fuel use that powered the Industrial Revolution.

They also identified nine short-lived drying spells in the northern tropics that followed a series of violent volcanic eruptions in the northern hemisphere. Volcanoes are a natural source of atmospheric sulphur.

Atmospheric pollution

The research confirms earlier suggestions that human atmospheric pollution sufficient to mask the sunlight and cool the upper atmosphere had begun to affect the summer monsoons of Asia, and at the same time stepped up river flow in northern Europe.

The change in radiation strength shifted the tropical rainfall belt, known as the intertropical convergence zone, towards the warmer southern hemisphere, which meant lower levels of precipitation in the northern tropics.

“The research presents strong evidence that industrial sulphate emissions have shifted this important rainfall belt, particularly over the last 100 years,” Dr Ridley says.

“Although warming due to man-made carbon dioxide emissions has been of global importance, the shifting of rain belts due to aerosol emissions is locally critical, as many regions of the world depend on this seasonal rainfall for agriculture.”