Governments of 110 nations have promised to beef up action to help people forced to leave their homes and cross borders because of natural disasters - and to take steps to prevent them having to flee in the first place.

Ministers and other officials adopted a non-binding “agenda” in Geneva on Tuesday to protect those displaced to other countries by earthquakes, volcanoes and climate-linked hazards such as floods, storms, droughts and rising seas.

Between 2008 and 2014, 184.4 million people were displaced by disasters, an average of 26.4 million people each year, the document noted, though there is no data to show how many people moved across international borders.

“Forced displacement related to disasters, including the adverse effects of climate change … is a reality and among the biggest humanitarian challenges facing states and the international community in the 21st century,” the agenda said.

Africa, Central and South America have seen the largest number of incidences of cross-border disaster-displacement, the document issued at the end of the meeting said.

Three years ago, the Swiss and Norwegian governments launched a consultation process to find ways to support people displaced to foreign countries by environmental crises, given that the vast majority cannot claim refugee status and there was little appetite for a new international law.

The Nansen Initiative’s final global consultation in Geneva this week ended with states committing to collect more data and knowledge on those affected, make better use of humanitarian protection measures such as temporary visas to help them, and reduce the risk of displacement in their home countries.

Jan Egeland, secretary-general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, said that back in 2012, “there was a lot of denial and scepticism that this was something to look at”.

But now there is widespread recognition among governments “that we have a huge, growing, neglected problem”, he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation from Geneva.

Countries whose people are likely to be displaced by climate impacts and other natural hazards - from Fiji to the Philippines and Madagascar - appealed for support at the meeting, he added.

“They explained that they are desperate - a big portion of their population is at risk, and they need help,” he said.

Walter Kaelin, a human rights lawyer and envoy for the Nansen Initiative, said effective ways to support disaster-hit people who cross borders already exist but need to be harmonised and used more systematically, particularly at a regional level.

“In a world where an international convention is not feasible - and maybe even not adequate, taking into account the huge differences from one region to another - the approach of the Nansen Initiative is a toolbox, and there are many, many tools,” he said.

Egeland said governments could provide those arriving with some form of legal status, and permits to stay and work.

States, UN agencies and civil society groups should consult affected people, and where possible help them obtain new housing and land in their own country so they can return home “with dignity”, he added.

Climate deal concerns

The Nansen protection agenda emphasises that much can be done to avoid people having to leave home due to disasters - from setting up early warning systems to strengthening infrastructure and boosting incomes and food security.

But efforts to adapt to climate change must also accept that some may have no choice but to move, it says.

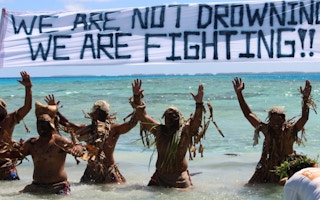

That prospect is most acute for small island developing states and countries with long low-lying coastlines that are at risk from erosion, flooding, submergence and other effects of rising seas, it adds.

Both Egeland and Kaelin expressed concern that the latest version of a draft UN agreement on climate change, due to be finalised in Paris in December, had removed any references to tackling climate-related displacement or migration.

“It has to figure in the (Paris) outcome,” said Kaelin.

States had already committed at earlier U.N. climate conferences to work on the issue - whether under the umbrella of adapting to climate change, or losses and damage caused by its effects, he noted. Officials in Geneva this week agreed the Paris deal should build on that, he added.

“This is ground zero for climate work - those people who have lost everything… those are the ones we have to recognise and help defend, compensate, make more resilient,” said Egeland. “I hope it will not drown in the big tug of war about (greenhouse gas) emissions.”