Last month, Princeton University’s endowment manager promised to eliminate holdings in publicly traded fossil fuel firms. It follows a similar move just weeks earlier, when over on the west coast of the United States, University of Washington, Seattle, had said that it will divest completely from such companies by mid-2027.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In Asia, Singapore utility Sembcorp Industries sold off its US$1.5 billion stakes in two coal power plants in India to a firm in Oman last month, a move that Sembcorp said will green its portfolio.

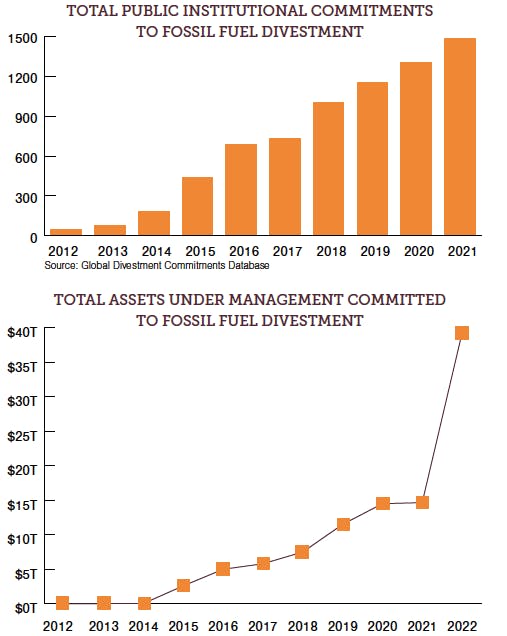

These institutes and corporations join big names like the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund and French postal bank in divesting from big polluters to the tune of US$40 trillion in just about a decade, according to US-based advocacy group Stand.earth.

But the divestment tide, created in part by American undergraduates appalled at their varsities’ support for fossil fuels, is facing a counter-current in recent years. Asset managers have said they prefer helping big emitters decarbonise, rather than ridding them from their portfolios.

Growth in divestment commitments from 2012-2021. Source: Global Divestment Commitments Database. [click to enlarge]

One worry is that when climate-conscious financiers sell polluters away, they end up being owned by private funds with less oversight and care for sustainability – thus not spurring any real-world decarbonisation.

“Private equity firms have increasingly been buying fossil fuel assets as others have looked to divest,” said a report last year by financial services firm Fitch Group. About 80 per cent of energy assets owned by the world’s top 10 equity firms are in fossil fuels, according to US non-profit Private Equity Stakeholder Project.

Big names in the financial world have reiterated such risks.

“[Divestment] is a very short-term fix,” Yuki Yasui, the Asia Pacific chief of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), said recently at an Eco-Business event. Member firms under GFANZ, one of the world’s largest climate finance groups with a combined US$130 trillion under management, commit to help their holdings reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Larry Fink, chief executive of the world’s largest asset manager Blackrock with nearly US$10 trillion of holdings, said this year that the firm “does not pursue divestment from oil and gas companies as a policy”.

Selling off stakes in fossil fuel firms today may also mean missing out on using their existing pipes and facilities for clean energy initiatives tomorrow, such as transporting clean hydrogen fuel or pumping carbon dioxide underground.

“Many of these assets are significant infrastructure that is basically impossible to rebuild,” Elizabeth Lewis, managing director and deputy head of ESG at private investment firm Blackstone, said at an event hosted by think-tank Economist Impact last week.

Stick and signal

But experts and activists warn that relying entirely on active management of polluters is not the optimal solution. Divestment remains useful as both stick and signal, they say.

While divesting from the entire fossil fuels sector would not spur any transformation, “tilting” away from the industry while keeping money in best-in-class firms provides a signal for energy firms to go green faster, said Professor Alex Edmans at the London Business School, at the Economist Impact event.

“Maybe divestment’s main power is not starving [firms of] capital, but giving incentives for industries to reform,” Edmans said. In a co-authored paper published in April, he advocated for green finance policies to encourage such forms of selective funding in “brown”, or highly carbon-emitting industries.

The paper also called for polluting industries to disclose publicly their progress with decarbonisation, to shield investors willing to fund their efforts from greenwashing claims. Privately sharing such information would not work, it said.

Divestment should also remain on the table as a threat should polluting firms not respond to prodding from investors, according to Professor Lawrence Loh, director of the Centre for Governance and Sustainability at the National University of Singapore.

“It should be a credible threat, otherwise [the managed] companies will not buck up,” Loh said, even as engagement should stay as the top option.

Some asset managers have already brought the hammer down on slow-moving firms. At the end of last year, Swiss asset manager UBS divested from five energy firms, including American giant Exxon Mobil, after three years of engagement under climate-themed funds. Scotland-based insurer Abrdn also told the Financial Times that it had divestment as a last step in its management plan.

“Engagement and divestment are too often presented as competing tactics, when in reality they are complementary,” said Simon Rawson, director of corporate engagement at UK non-profit ShareAction.

“To succeed, engagement requires an escalation strategy. Investors cannot solely make requests but must also set out what they will do if a request is ignored,” Rawson said.

Rachel Cheang, a member of Singapore’s Students for a Fossil Free Future advocacy group, agrees that divestment must be part of the engagement toolkit. The group had launched a campaign asking Singapore universities to cut ties with fossil fuel firms in January, after what Cheang said was years of hearing school administrations say they would engage the polluting industries without concrete evidence.

“If the universities are willing to [engage] and we see that in action, then the divestment movement is prepared to hold them accountable to it,” Cheang said, adding that the movement is about being critical of how effective managing polluters is, rather than “cancelling” an entire industry.

Cheang also pointed to the moral impetus for divesting.

“It is about taking control of the narrative, in saying that the fossil fuel industry should no longer have the stronghold over our economic decisions,” she said. Fossil fuel firms, beyond being invested in by Singapore universities, also sponsor concerts, provide scholarships and host networking events.

While the debate on divestment’s role as a climate solution continues, parting ways with fossil fuel businesses could increasingly become a rational economic move – the idea being that facilities like coal plants risk becoming costly stranded assets, as carbon taxes take their toll and cheaper renewable capacity comes online.

The current energy crisis fuelled by the Russian-Ukraine war, and the scramble for more coal and gas in Europe, is generally seen as a temporary blip.

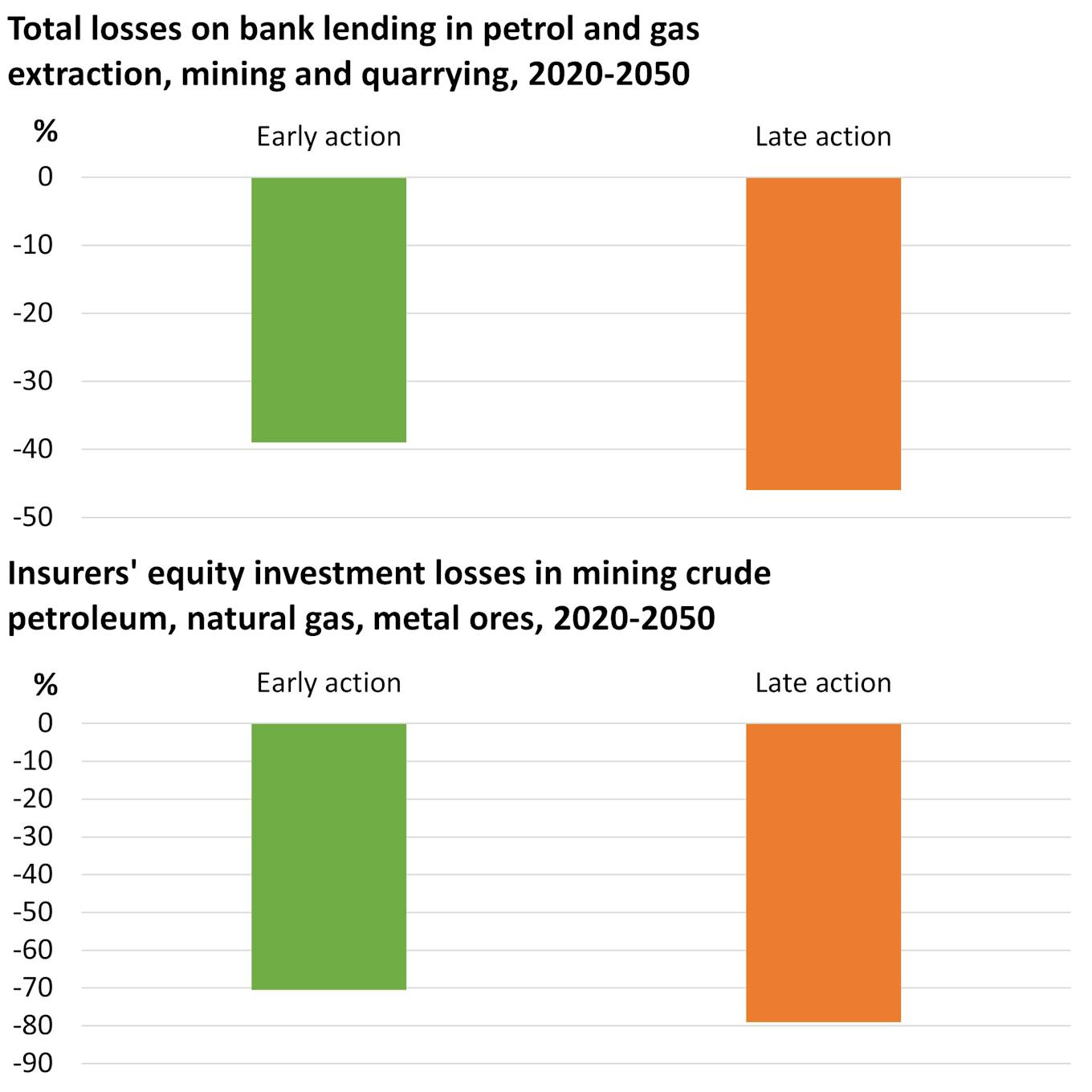

A Bank of England 30-year scenario paper released in May found that UK banks expect to reduce lending to businesses like fossil fuel extraction and mining by over 40 per cent by mid-century, while insurers would shed 70 per cent of their investments in mining oil, gas and metal ores. The figures climb even higher for a scenario where the global decarbonisation pathway is delayed.

Projected losses in investment in the UK banking and insurance sectors, based on the Bank of England’s 30-year models. Data: Bank of England. [click to enlarge]

“It suggests that [financial firms] are not baking in an expectation of material transition within these sectors. In the absence of clarity of what is going to happen, they are pricing in obsolescence,” said Chris Faint, head of the climate hub division at the Bank of England.

In such a situation, the sudden drops in funding could rattle the economy, Faint added – a further impetus for governments to look at how to facilitate an orderly green transition.

Asia

The divestment conversation could be especially complex in Asia, where fossil fuels dominate rapidly emerging economies.

On one hand, getting enough information about polluters – key to successfully managing their decarbonisation – is tricky for asset managers. The data gap in Asia and the Middle East gets in the way of making “detailed transition assessments”, according to Zoë Knight, group head of the centre of sustainable finance at HSBC bank.

The struggle to field good data, while pertinent in Asia, has also been raised globally. Some members in the GFANZ climate coalition have complained that reporting requirements, which include annual updates, are too onerous, according to Financial Times reports.

On the other hand, Asia’s dependency on fossil fuels and the presence of many developing markets could create higher risks of negative socio-economic impacts with blunt divestment strategies.

“Coal, over time, is probably unnecessary in most of the world. But I wouldn’t try and tell that to an Indian power producer just yet; it is a very important source of energy,” said John Browne, co-founder of investment firm BeyondNetZero and former chief executive of UK oil major BP. Coal makes up over half of India’s installed power capacity.

Loh, the National University of Singapore don, said that the region will need more help in the form of finance for research into decarbonisation strategies, and better government policies to help workers in polluting industries find new jobs.

The question of what’s next after divestment is also on the mind of Cheang, from Singapore’s Students for a Fossil Free Future group.

She pointed to the building of hydropower dams along Southeast Asia’s Mekong River, which can provide low-carbon electricity, but displaces huge swathes of local communities and biodiversity. Singapore started importing hydroelectricity from Laos this year as part of its plans to decarbonise its power sector.

“I think the divestment movement hasn’t done a very good job yet of making sure that after we divest from fossil fuels, the new solutions do not cause the same harm that the fossil fuel industry did,” she said. Future initiatives will need to address this issue, she added.