A recent coal tax increase in the Philippines is a move that is expected to bring down the price of electricity—and curb the country’s carbon emissions.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The coal industry has been exempt from paying excise tax for the last 40 years, with the tax rate remaining unchanged since 1988, despite the industry’s rapid expansion in the country. This has assured the coal industry of bumper returns, but consumers are left with the burden of absorbing the risks of pricier electricity from imported coal.

“The passage of the coal tax hike is just and necessary to help protect our people and environment from the devastating impacts of coal consumption,” commented Angela Consuelo Ibay, head of WWF-Philippines’ Climate and Energy Program.

In an email interview with Eco-Business, energy finance analyst Sarah Jane Ahmed of US-based think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) said that the country’s dependence on coal was a result of subsidies that dictate the market price.

“The more the Philippines imports diesel and coal-fired power capacity, the more it exposes the electricity system to price volatility, regardless of which foreign supplier we turn to. Hence the high electricity costs,” she told Eco-Business.

Source: Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities

A coal tax, on the other hand, takes the burden of inflation costs away from consumers and levels the playing field, she added.

In December 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) bill, which includes excise and value added taxes on imported coal from Indonesia and Australia.

The tax reform measure raises the excise tax on coal from its current rate of US$0.20 per metric tonne US$1 up to US$3 per metric tonne over the next three years.

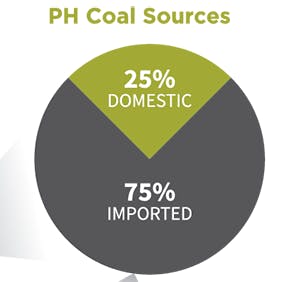

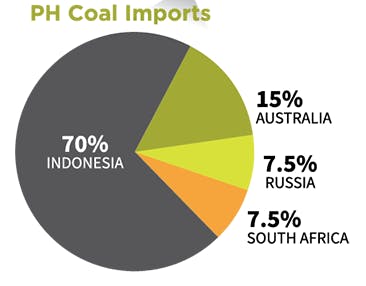

The Philippines imports 75 per cent of its coal supply. Out of the total supply of imported coal, 70 per cent comes from Indonesia while 15 per cent from Australia.

Source: Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities

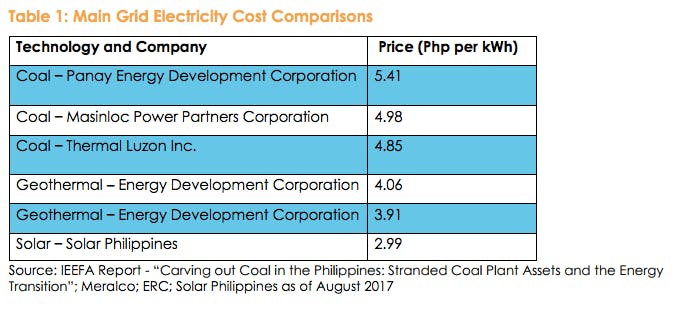

The Southeast Asian country pays one of the highest electricity rates in the region; industry rates are US$0.16 per kilowatt-hour (kwh) and household rates at US$0.17 per kilowatt-hour (kwh).

A 2016 study by Australia-based International Energy Consultants (IEC) showed the rates of Manila Electric Co. (Meralco)—the country’s largest power distributor—to be the third highest in the region, fourth in Asia Pacific and 16th worldwide.

Coal-fired power plants are currently the country’s biggest source of electricity and are projected to be the primary driver of growth in the infrastructure segment over the next 10 years, according to Fitch Group’s BMI Research in an August 2017 report.

“

The more the Philippines imports diesel and coal-fired power capacity, the more it exposes the electricity system to price volatility, regardless of which foreign supplier we turn to. Hence the high electricity costs.

Sarah Jane Ahmed, energy finance analyst, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

Opposing the tax measure for fear that it will result in higher overall electricity costs for the Philippines makes no sense, commented Ahmed.

“Coal tax is part of the operating cost, not the fuel cost so (any change in the electricity price) should not automatically be passed on to consumers. A coal tax adopts a polluter pays principle, which shields consumers from paying,” Ahmed explained.

“Any increases in the price of electricity must be approved first by the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC),” she added.

Quite the reverse, putting a price on pollution will reduce the dependence on imported coal and encourage cheaper, cleaner energy options over the long term.

What about Mindanao?

Mindanao, the second largest island in the Philippines, is the most coal-dependent of the archipelago’s three island groups, accounting for 33.8 per cent of installed generating capacity, based on latest data from the Department of Energy.

Ahmed noted that over a million households in Mindanao still do not have access to electricity. Energy-poor households are usually removed from the main grid, which is largely coal-powered and centralised.

“That means they are better served by decentralised mini-grid solutions powered by renewable energy with batteries, systems that can be rapidly deployed where needed as a cost-effective way to establish sustainable energy access,” she said.

The Visayas, another of the country’s major regions, is already 47.9 per cent reliant on renewable energy generation.

The tax hike is expected to bring in P2 billion (almost US$40 million) in total revenues this year, according to the Department of Finance.

This would translate to much needed investment in infrastructure and social development like the government-initiated Ambisyon 2040—the long-term vision of the Philippines to align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals agenda and adapt it to the local context.