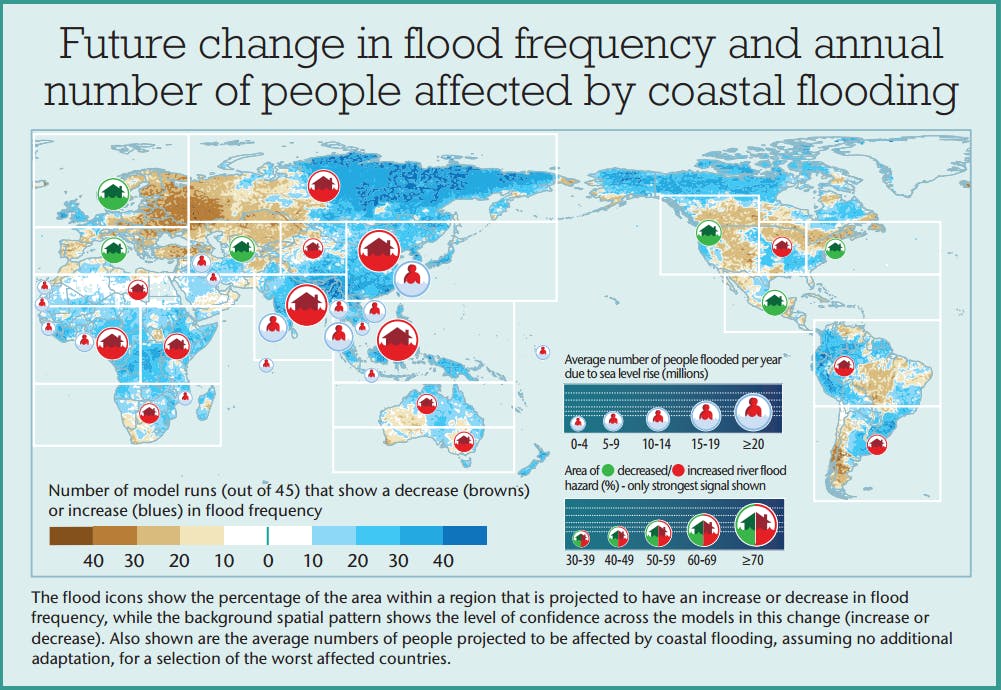

By the end of the century, Singapore could see almost 445,000 people a year being adversely affected by flooding if no efforts are made to mitigate climate change. The frequency and intensity of flooding events in Southeast Asia is also set to increase by 77 per cent.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

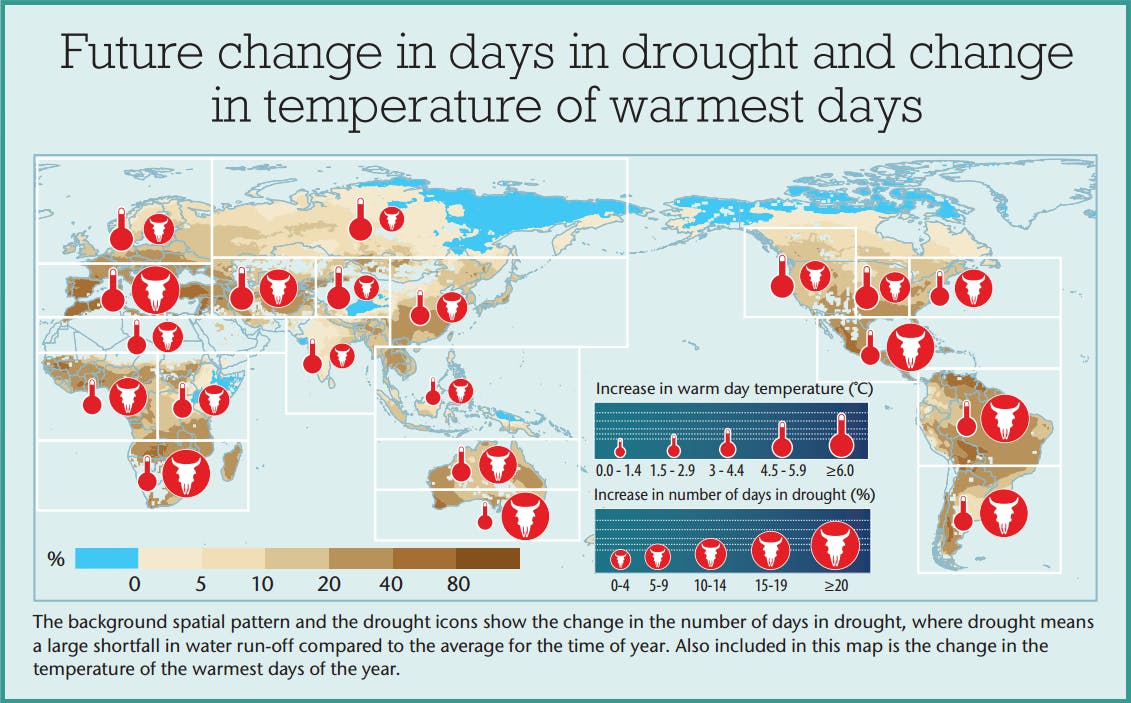

Even as flood risks in the region increase, warm day temperatures will increase by an average of 4.3°C and the number of days in drought will increase by 5 per cent.

But if the world takes rapid and significant action to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions such that they peak in 2040 and then decline, these numbers could be reduced. The number of people in Singapore affected by flooding would plummet from 445,000 to 20. In Southeast Asia, the increase in frequency of flood events would be limited to 51 per cent, and warm day temperatures would only increase by 1.2°C. The projected increase in drought days would also be reduced to 3 per cent.

These findings were revealed in a report on the ‘Human Dynamics of Climate Change’, launched in London on Wednesday by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

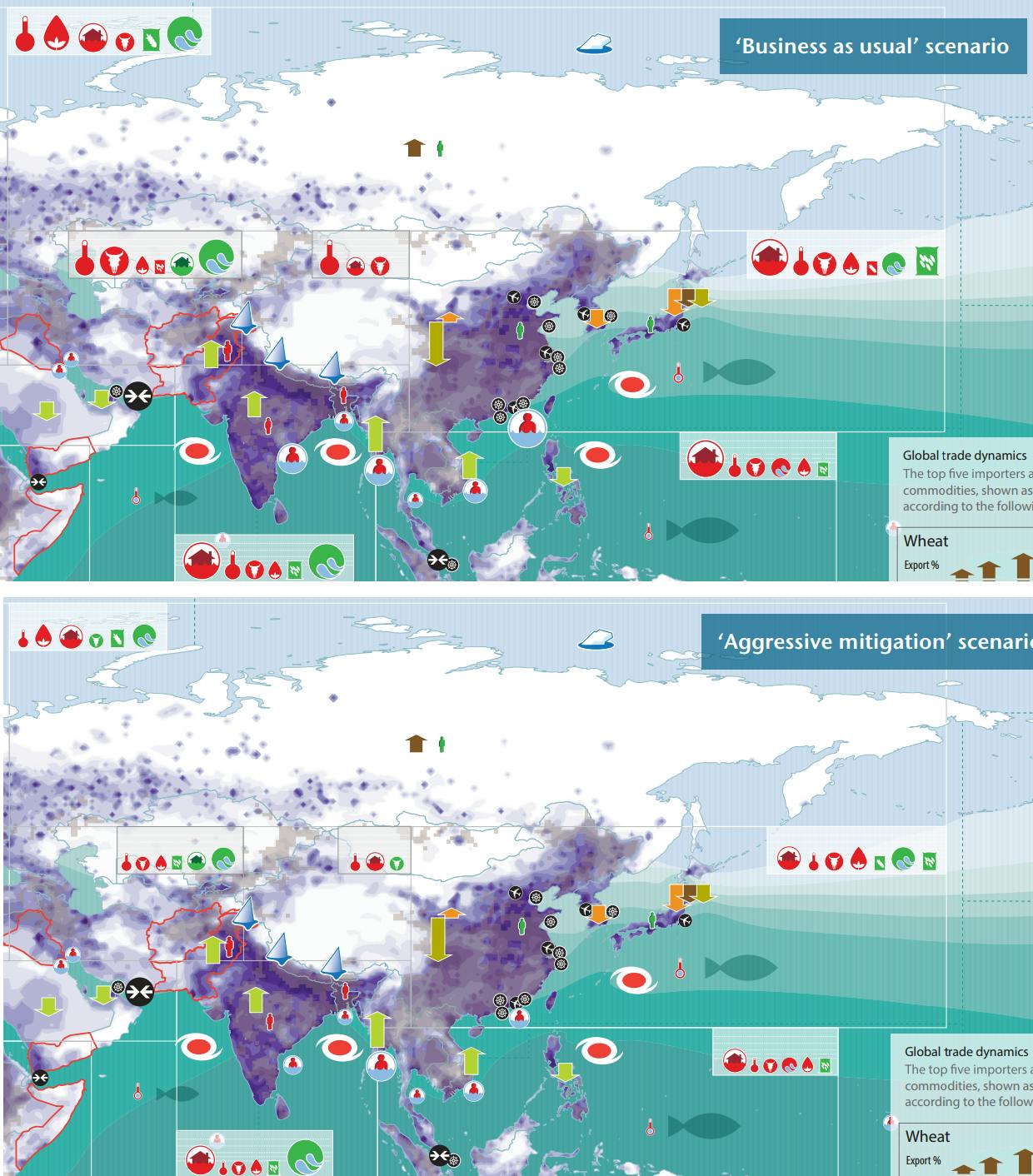

Developed by the UK Met Office Hadley Centre, the report examines how weather patterns, natural disasters, trade flows, food production, and water security will be affected if greenhouse gas emissions continue along a “business as usual” scenario.

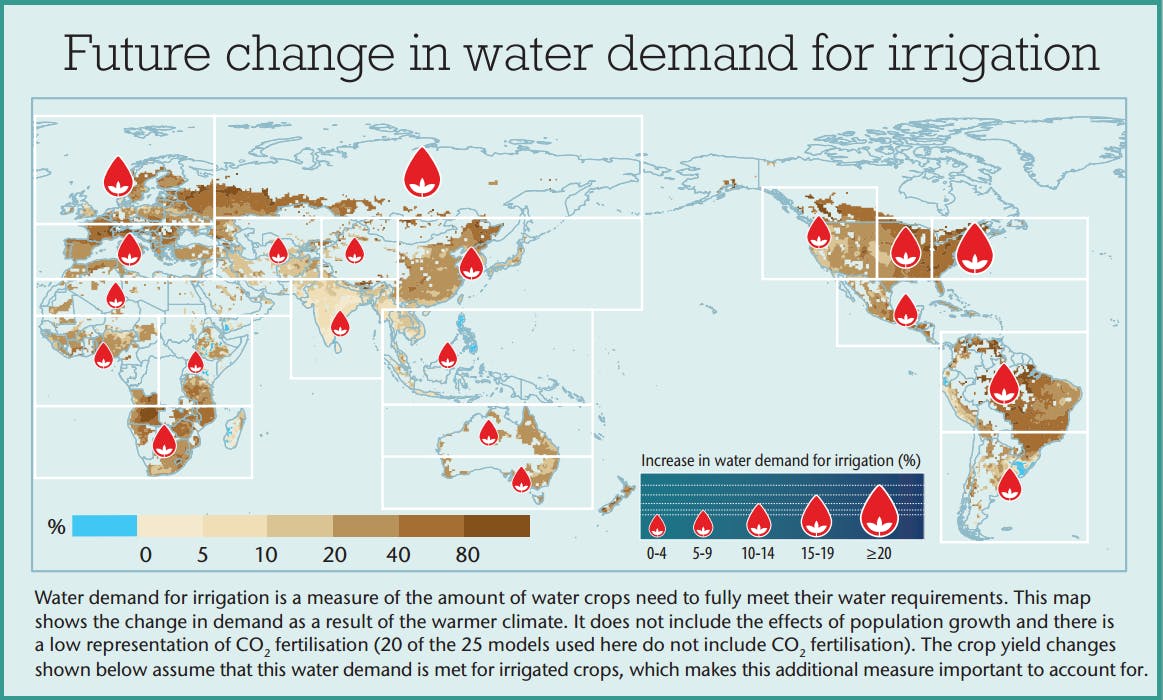

The findings have been consolidated in a comprehensive map which shows the interconnected nature of the impact of climate change. Present day scenarios of trade flows, population density and resource scarcity are presented alongside predicted changes on the map.

In Asia, the factors determining the impact of climate change include high population densities across much of South and Southeast Asia, rapidly growing populations in East Asia, and existing shortages of food and water in the region.

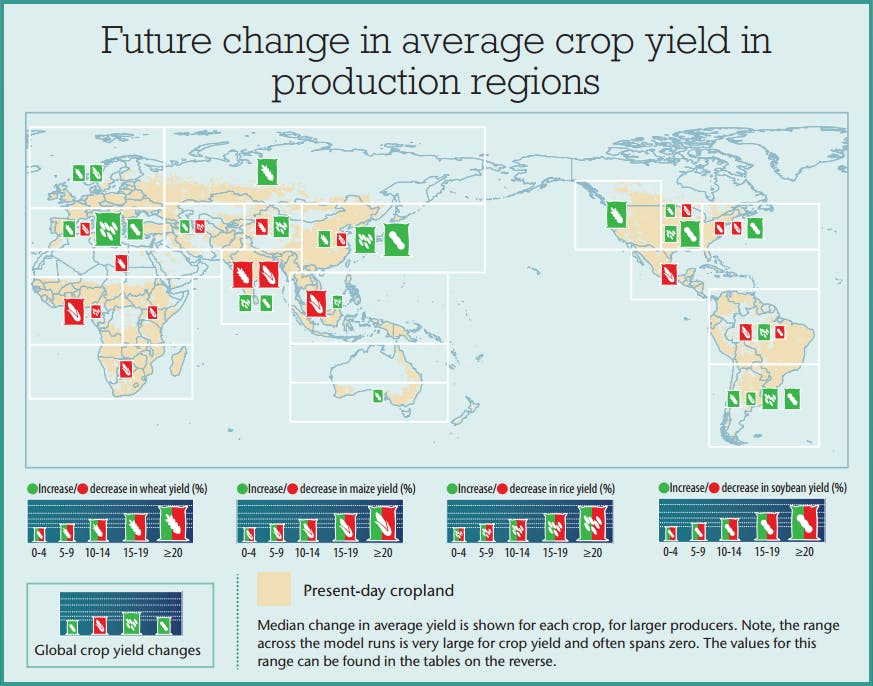

Water stress will be compounded by food stress in the region as well. The production of Wheat and Maize are set to decrease in South Asia and South East Asia, which are major global exporters of these crops. However, rice yields will increase slightly across the region.

Mark Simmonds, Foreign Office minister, said that the map showed “how the impact of climate change on one part of the world will affect countries in other parts of the world, particularly through the global trade in food”.

Simmonds said that this highlighted the global nature of the problem and that “no country is immune, and we all need to work together to reduce the risks to our shared prosperity and security”.

Julia Slingo, Met Office chief scientist, said that the report has used “the latest science to assess how potential changes in our climate will impact people around the world”.

The outlook is bleak, she said, adding that “while we see both positive and negative impacts, the risks vastly outweighed any potential opportunities”.

In addition to the main map, the Met Office also published two additional maps which consolidate all the different types of impact into one diagram. One of these maps presents an alternative scenario of what the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) has deemed “aggressive mitigation”, wherein global climate emissions peak by 2040 and then decrease.

Adverse impacts such as flooding in Asia are visibly reduced if aggressive mitigation measures are undertaken.

The urgent need for mitigating climate change echoes the findings of the IPCC’s recently released fifth assessment report (AR5), which revealed that the emission of greenhouse gas emissions had accelerated despite reduction efforts.

The report cautioned that delaying mitigation efforts would “increase the difficulty and narrow the options for limiting warming to 2°C”. Scientists say that it is necessary for suface temperature increase to stay within this limit if the world is to avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change.