On October 20, 2018, gunmen shot dead nine sugarcane farmers in Negros Occidental, the Philippines. The victims were defending a patch of a plantation they had tilled for generations.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The incident highlighted the conflict between land-intensive industries such as mining, logging, and agribusiness and social and environmental justice in the Philippines, which this year was declared the most dangerous country in the world for environment and land defenders.

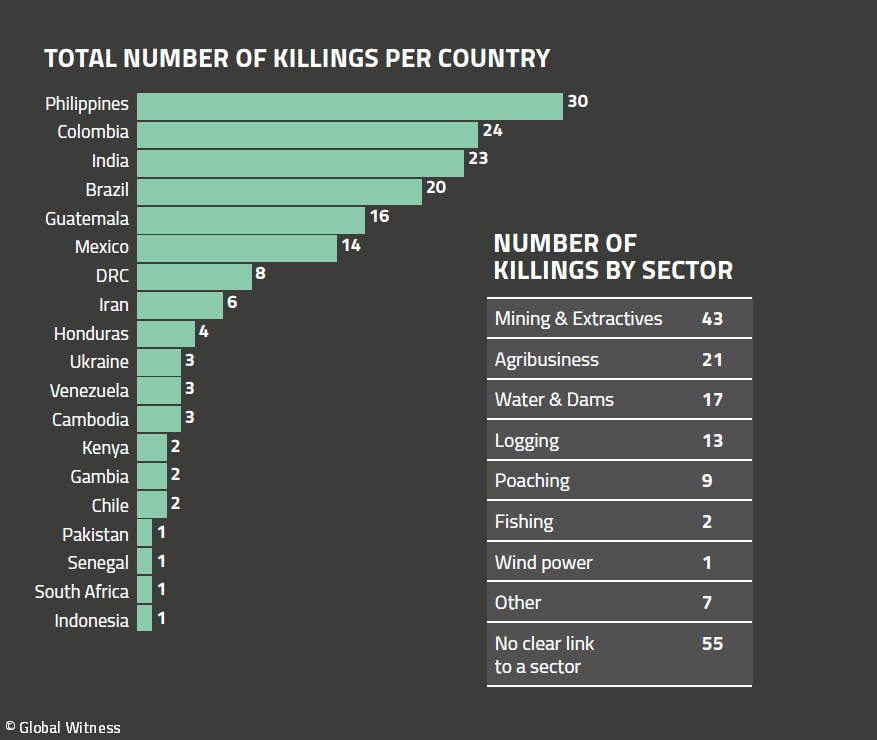

According to international non-profit Global Witness, which published the new report titled Enemies of the state? How governments and business silence defenders, 30 activists were killed in the Philippines last year.

Of the 164 land and environmental activists killed around the world in 2018—a drop from the 207 individuals killed in 2017—58 lost their lives in Asia, the second most dangerous region after Latin America.

India was Asia’s second most dangerous country for environment and land defenders in 2018, where 23 defenders were killed, including the massacre of 13 people when police opened fire on a crowd of around 20,000 protesting against a copper smelting plant in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. The activists claimed the plant was polluting the air and threatening the local fishing industry.

Corruption in business and politics allows private interests and the drive for profit to interfere with the rule of law and the governance of whole populations.

Heather Iqbal, senior communications advisor, Global Witness

A significant number of people were killed in 2018 defending their land against a business considered clean—the renewable energy industry.

In Guatemala, which suffered the sharpest rise in killings—up from 3 in 2017 to 16 last year—the attacks were against indigenous people protesting against the San Andres and Pojom II dams from the San Andres hydroelectric project, which defenders complained has polluted the water, destroyed crops, and depleted fish stocks.

Denouncing the killings, Global Witness’ senior communications advisor Heather Iqbal said addressing the root causes of attacks on defenders, including corruption in business and politics, is the only effective way of tackling the problem.

“Corruption in business and politics allows private interests and the drive for profit to interfere with the rule of law and the governance of whole populations,” she told Eco-Business.

Why protecting defenders matters for business

Acknowledging the contribution defenders make to protecting and promoting universally recognised human rights and ensuring sustainable development, industry body Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) last year rolled out a policy that provides defenders with the opportunity to lodge complaints against RSPO members whose business operations put defenders’ safety and security at risk.

The RSPO warned that members found threatening or causing harms to defenders would face suspension or termination from the body.

Former Unilever chief executive Paul Polman who currently chairs B Team, a leading non-profit initiative formed by a group of global businesses, has highlighted the economic benefits of business, government and civil society collaborating to uphold and protect the rights of defenders.

“Given the increasing vulnerability of human rights defenders and shrinking space where they can operate safely, business has a role and a responsibility to defend and promote fundamental rights and freedoms,” he said in a research paper titled, The Business Case for Protecting Civic Rights, published last year.

The study showed that limits to civic freedoms have negative economic outcomes. It recommended for companies to include human rights in impact and risk assessments across supply chains.

These findings align with Iqbal’s recommendation for businesses to conduct checks on their supply chains and ensure their operations and those of their suppliers’ are not driving land grabbing or environmental harm.

“Banks, too, that pump money into industries, must take responsibility and do proper due diligence on their investments to guard against environmental, social and governance risks,” Iqbal said.

“We’re keen to see governments introduce regulations that oblige companies to demonstrate that the products they buy or trade come from land that has been legally and ethically acquired,” she said.

“Timber laws in the US and the EU already require companies to take steps to ensure they aren’t driving deforestation through importing illegal timber. There’s currently no such regime for land grabbing.”