Too similar? The RSPO logo and the marijuana leaf. Image: Eco-Business

An executive at one of the world’s biggest buyers of palm oil was recently overheard saying that their company does not use the logo of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) on its packaging because the brand mark looks too much like a marijuana leaf.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Not a good look for companies trying to sell packaged goods like biscuits, instant noodles and ice cream that contain palm oil—unless, perhaps, the product is on supermarket shelves in Canada, Uruguay or certain states in the United States where weed is legal.

The most common label for sustainable palm oil, RSPO’s logo—which depicts the fronds of an oil palm—is often referred to as “the green spider”. Whatever its visual qualities, the reality is that companies do not like using it.

Eco-Business found only one product bearing the RSPO trademark from a casual inspection of the shelves at Singapore’s biggest supermarket chain, NTUC Fairprice (which was called out by RSPO for making inaccurate claims about the sustainability of the palm oil in its own-label brands in 2017) last week. It was a tub of Cabbage brand “vegetable” cooking oil, which was made from a mixture of certified and uncertified palm oil represented by the RSPO ‘Mixed’ trademark (update, 17 October: Eco-Business has been informed that there are actually six brands at NTUC Fairprice that bear the RSPO logo—all of them vegetable oil).

“

Palm oil is a complex issue. It’s easier [for brands that use it] to keep quiet.

Benjamin Tay, executive director, People’s Movement to Stop Haze (PM.Haze)

Quaker Oat biscuits made by PepsiCo, Nissin’s Cup Noodle, Plain Crackers by Meiji, Oreo cookies by Mondelez, and Ferrero’s Nutella spread are all RSPO-certified (Ferrero products use one of the highest standards of RSPO certification, of which there are four types). But none carry the RSPO logo on their packaging.

In the United Kingdom, an actively anti-palm oil market where retailers Iceland and Selfridge’s have committed to remove the ingredient from their products, some own-label products sold by supermarket chain Sainsbury’s, an RSPO member, communicate that they contain certified sustainable palm oil on their packaging, but do not carry the RSPO logo.

One of the few brands to display the green spider in the UK is Nutoka, an own-brand chocolate hazelnut spread from low-cost retailer Aldi that is a competitor of Nutella.

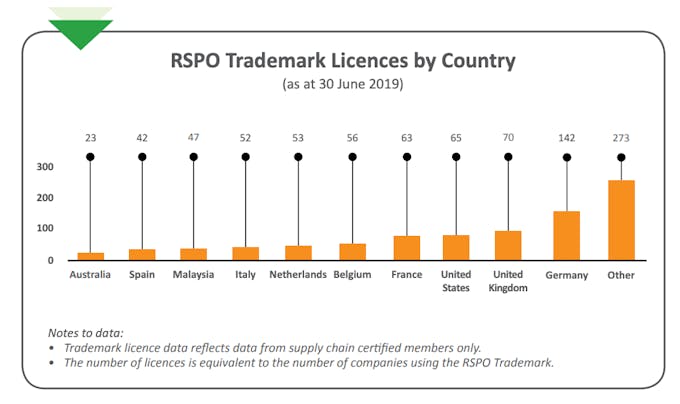

Just 50 companies use the RSPO trademark on about 300 different products, a small number given that palm oil is an ingredient in about half of all supermarket products. Most RSPO trademark users are in Europe, where concern about how palm oil is grown is highest.

Why so shy?

A spokesperson for Mondelez said that the company does not use the RSPO logo “because it is not well known to consumers”.

A spokesperson for Nestlé, which was suspended by RSPO last year for failing to submit progress reports, did not say why it doesn’t use the trademark, only that it is “committed” to using 100 per cent RSPO-certified oil by 2023.

Eco-Business also posed questions to Unilever, the world’s biggest palm oil buyer, and Mars, both of which have promised deforestation-free supply chains by 2020. Neither responded.

Anita Neville, the senior vice-president of corporate communications at palm oil company Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), previously worked for sustainability consultancy Rainforest Alliance on certification. She says that palm oil is rarely the main ingredient in products such as chocolate and biscuits, so it isn’t the priority for brands to label what they use as sustainable.

Packaging is prime marketing real estate and, with space increasingly taken up by health and nutritional information due to government regulations, there is less room on the pack to tell consumers about the sustainability of the ingredients, she added.

Even if palm oil is the only ingredient that is certified sustainable, the crop’s poor reputation, particularly in the West, has meant that few manufacturers want to draw attention to the fact that they’re using it, sustainable or not, she said.

What does sustainable palm oil actually mean?

Part of the problem lies with RSPO. Though the certifier has toughened its definition of sustainable palm oil, introducing new rules a year ago that forbid its members to cut down tropical forests to cultivate the crop or grow on carbon-rich peatlands, many remain unconvinced that the RSPO label genuinely stands for responsibly grown palm oil.

Green groups have long accused the organisation of being too lax on its members, which include NGOs as well as consumer goods companies and growers, and a lack of faith in RSPO has given rise to another certification body, the Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG), which claims to have higher sustainability standards.

Even then, the term “sustainable palm oil” means little to some environmentalists and conscientious consumers, who associate the oil with chainsaws and starving orangutans roaming scorched landscapes, despite the industry’s efforts to clean up its act.

While rogue actors in the sector continue to tear down and burn Indonesian rainforests despite a freeze on plantation expansion ordered by the country’s president last September, sustainably grown palm oil does exist.

Many growers, including Neville’s employer GAR, have no deforestation, no peat development, and no exploitation (NDPE) policies in place, assess land for high conservation value before developing new plantations, and do not deliberately burn land to clear it—the cause of Indonesia’s annual haze outbreaks that choke much of the region, including 2019, the worst year for transboundary air pollution since the great haze of 2015.

But only 19 per cent of all palm oil sold worldwide is certified sustainable by RSPO, and it is not getting any easier to sell the good stuff.

“Label or no label, what is best for the palm oil sector and for forest conservation is that consumer goods companies buy certified sustainable,” said Neville. “We still have a situation where more volume is produced as certified than is sold as certified. That has to change if we want to see more producers joining the RSPO.”

She pointed to a recent comment made by Jeremy Goon, chief sustainability officer of Wilmar International, the world’s biggest palm oil trader, that RSPO has not attracted any new producer members in the last six years.

Growers think palm oil’s image might improve if more companies promoted their sustainable palm oil use. A former RSPO associate privy to board meetings recounts constant battles between growers who complained that buyers wouldn’t promote sustainable palm, and buyers who questioned the credibility of the supply. “Meetings got boring. It was always the same fight,” they said.

A rare example of a brand that promotes its use of sustainable palm in Southeast Asia is Singapore Zoo, which proudly displays its use of sustainable certified palm oil in its premises.

However, the Temasek-owned attraction was hammered by Teresa Kok, the vociferous palm-defending primary industries minister of the world’s second biggest producer, Malaysia, six months ago, for “sensationalised displays” at the zoo’s orangutan enclosure that draw attention to the plight of the species as a result of palm oil production.

Kok, who is at the centre of a cultural and political row with the European Union over its decision to ban palm oil imports for use in biodiesel due to deforestation links, has said that that Southeast Asian countries including Singapore, home to the headquarters of a number of major palm oil players, need to present a united front in supporting the industry. Malaysia has called the ban “discriminatory”.

Dr Lee Hui Mien, vice president of sustainable Solutions at Mandai Park Holdings, of which Singapore Zoo is a part, told Eco-Business that the zoo has a “unique opportunity to engage with the five million guests that visit our parks annually… about wildlife conservation issues.”

The palm-free movement

But many companies seem much more willing to tell their consumers they are palm oil-free than promote products that contain sustainable palm.

The palm oil-free movement has gathered serious movement in Europe, and multinational brands such as UK-based Lush cosmetics are now marketing their palm oil-free credentials to consumers in Asia, even Southeast Asia, the heartland for a trade on which millions of farmers and their families rely to make a living.

In a promotion that started last year, Lush—which has admitted that palm oil is so widespread that its derivatives are hard to weed out completely from its product range—sold shampoo bars in the form of orangutans to highlight the decline of a species for which palm oil is widely blamed.

The orangutan is a popular symbol for palm oil-free products. Image: POFCAP

The orangutan is also the symbol of the International Palm Oil Free Certification Trademark Programme (POFCAP), a certification scheme for palm oil-free products founded in Australia last year. To date, POFCAP has certified 1,100 products certified from 26 companies.

Being palm oil-free is such a powerful marketing claim that some companies, whose products never contained palm oil to begin with, are echoing it to imply that their products are healthier, said one industry expert (palm oil’s health effects are hard to determine, because it is found in so many products).

There are now numerous consumer guides to “palm oil free” products, and laws requiring food manufacturers to clearly label palm oil as an ingredient so that palm-phobic consumers can avoid them.

But boycotting a vegetable oil that is cheaper and more resource- and land- efficient than others such as rapeseed and soy is not the answer, the industry’s supporters say, among them Singapore Zoo, which argues that moving away from palm oil could drive up demand for less productive vegetable oils and lead to greater loss of wild habitats. Meanwhile, the reluctance of companies to communicate their use of green palm is not helping attempts to improve the sustainability of the sector and give consumers less reason to avoid the oil.

In April, Singapore-based environmental group People’s Movement to Stop Haze (PM.Haze), with the help of advertising agency Havas, launched an app called EcoCart to help Singapore online shoppers identify which products contain palm oil, and prompt them to switch to products that contain the green variety. The app has attracted just 115 users and led to fewer than 300 switches to more sustainable products.

“The challenge has been identifying the products that use sustainable palm oil by reading through the certificates on RSPO’s website. Due to the sheer number of products out there, it has not been something we have had the capacity to do,” says Benjamin Tay, executive director of PM.Haze.

Tay said that Southeast Asia consumers do care about buying sustainable palm oil, and make the connection between buying green palm and a reduction in the haze air pollution that bad cultivation practices are linked to. “Providing opportunities for consumers to make haze-free product choices is very important,” he told Eco-Business.

Though those opportunities are small now, RSPO reports a 25 per cent increase in the use of its logo over the last year, which the organisation says is “a big step in the right direction.”

“We believe that as stakeholders and consumers become more aware of the issues and opportunities surrounding sustainable palm oil, they’ll work to influence manufacturers by asking them to use the RSPO trademark,” an RSPO spokesperson said.

The organisation added that the onus should not be on consumers to check that all the “right” trademarks are on the products they want to buy. “Sustainability should be the norm,” it said, and governments should introduce “binding rules to ensure companies follow high standards to act responsibly and address social and environmental issues.”

It added that it has no plans to tweak its logo because of any similarities to the plant popularised by the likes of reggae legend Bob Marley. “We don’t anticipate RSPO membership changing the logo at this time,” RSPO told Eco-Business.