The forced shutdown of Philippine broadcaster ABS-CBN’s radio and television operations threatens not only press freedom, but is a blow to environmental journalism in a country where issues such as mining, logging, and coal have strong links to corruption, green activists say.

The Philippines’ largest broadcaster was ordered off-air last Tuesday (5 May) by the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC), which awards broadcasting licences. The commission said ABS-CBN Corp’s franchise had expired the day before, and directed the network to “cease and desist” television and radio broadcasting operations.

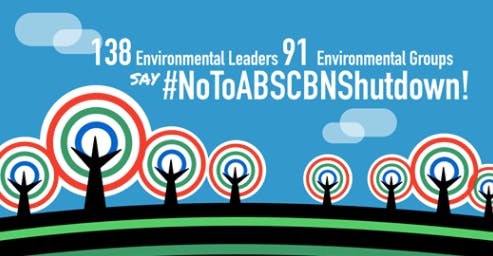

Greenpeace Southeast Asia, 350.org and Extinction Rebellion were among the environmental groups which signed a petition, demanding for the cancellation of the cease and desist order against the ABS-CBN. Image: Kalikasan

Parliamentary bills for its franchise renewal have been filed since 2014 when Benigno Aquino III was president. But lawmakers dominated by current president Rodrigo Duterte’s loyalists sat on a decision over the past six months that would have allowed the station to keep operating under a new license. Congress cited the coronavirus lockdown as one of the reasons why it was not able to tackle the pending legislation.

Yeb Saño, executive director of watchdog Greenpeace Southeast Asia, said an assault on freedom of speech is also an environmental issue.

“All the environmental problems we face today are issues of justice and rights,” Saño told Eco-Business.

“Environmental issues like mining, logging, and coal have strong linkages to corruption, the pollution of industries and politicians. If we see an assault on press freedom, then journalists will think twice before they go in the dangerous path of reporting on the environment.”

Saño also noted how the Philippines was named Asia’s most dangerous country for environmental defenders in a 2017 Global Witness report.

Out of the 48 killings recorded in the country in 2017, the majority of activists died while protesting against palm oil, coffee, tropical fruit and sugar cane plantations.

Global Witness previously blamed the Duterte administration’s anti-drug campaign, in which the police has been accused of executing almost 30,000 suspected drug pushers, for the increasing violence against environmental defenders.

“If we combine the closure of ABS-CBN, which is a valuable advocacy partner for the environment, along with the country not being a safe place for environmental activists and journalists, then it is truly alarming,” said Saño.

“

All the environmental problems we face today are issues of justice and rights.

Yeb Saño, executive director, Greenpeace Southeast Asia

Chuck Baclagon, campaigner for climate advocacy organisation 350.org, echoed how environmental defenders like journalists and activists were already on the receiving end of human rights violations by the state and corporations that harm the environment.

“Losing a media outfit that does a lot of coverage on environmental issues puts more frontline defenders at risk and further strengthens the already-existing impunity of such violators,” Baclagon said.

Greenpeace Southeast Asia and 350.org are among more than 200 parties that have signed a protest letter denouncing the closure of ABS-CBN.

They cited how the news station, with a “wide viewing and listening public”, has spearheaded documentaries that exposed destructive mining operations and the creeping threat of land reclamation disguised as a rehabilitation programme in Manila Bay.

The letter, put together by the non-profit Kalikasan People’s Network for the Environment, also petitioned for the cancellation of the cease and desist order against the station.

“Environmental journalism in the time of pandemics is needed, now more than ever,” the petition stated, calling the order a direct attack against free expression and press freedom at a time when millions of Filipinos are in need of timely and crucial information.

In the ABS-CBN newsroom, the company’s president and chief executive officer Carlo Lopez Katigbak delivers a statement during the final broadcast on air of its flagship news programme TV Patrol, following the cease and desist order of the National Telecommunications Commission. Image: Fernando G. Sepe Jr./ ABS-CBN News

“

The bulk of the Filipino audience still prefers television … With slow internet speed in the Philippines, especially in rural areas, I don’t think I can reach the same audience by just being online.

Kristine Sabillo, environment and health reporter, ABS-CBN

The end of an era for media’s green stalwart?

Although Filipinos have other TV and radio giants like GMA Network and TV 5 to turn to, ABS-CBN is the country’s largest free-to-air TV broadcaster with a total day audience of 41 per cent in the primetime block for 2020. It also operates 19 radio stations across the country.

“It’s true that we’re not the only news network out there but I’d like to think we’re one of those in the mainstream media that have regularly highlighted environmental issues,” Kristine Sabillo, ABS-CBN’s environment and health reporter, told Eco-Business.

She said this is one of the values of the network’s ABS-CBN Foundation, which was led by the late Gina Lopez who, like her uncle, Lopez Holdings Corporation chairman emeritus Oscar Lopez, was a staunch environmental advocate.

The younger Lopez set up the foundation’s environmental advocacy arm, Bantay Kalikasan (Nature Watch). In the early 2000s, it used the company’s media resources to expose individuals, agencies and companies who abused the environment.

Sabillo said she could still report for ABS-CBN’s website, as the government order does not affect the network’s other subsidiaries such as its cable news channel and digital platforms. But not being able to report for television and radio will be “frustrating”, she said.

“The bulk of the Filipino audience still prefers television and I’ve seen the biggest impact of my stories through that platform. With slow internet speed in the Philippines, especially in rural areas, I don’t think I can reach the same audience by just being online,” she said.

“ABS-CBN has produced a lot of shows highlighting environmental issues and it’s truly a tragedy that Filipinos won’t be able to watch them anymore if we don’t get our franchise back.”

In complying with the government’s order, the broadcaster said in a statement that it “trusts that the government will decide on our franchise with the best interest of the Filipino people in mind”.

Opposition senators called on NTC to reconsider its decision. The last time the broadcaster was closed down was in 1972 when former dictator Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law. It did not go back on air until 14 years later, when the regime was overthrown.

Duterte has been vocal about his disdain for the station, the majority of which is owned by the Lopez family, one of the Philippines’ richest clans. The media giant has extensively covered the government’s notorious war on drugs, but Duterte’s displeasure goes back to the 2016 presidential election when he accused the network of refusing to run his campaign commercials.