Hãy đọc câu chuyện này bằng tiếng Việt

Southeast Asia’s de-facto renewables frontrunner Vietnam will, over the next seven years, turn to wind turbines to lead its growth in green electricity capacity instead of big solar projects – though building owners are still encouraged to install panels for their own use.

At the same time, imported natural gas, a debated “bridge” fuel for the energy transition, will take a chunk off Vietnam’s heavy coal reliance.

These decisions, all but finalised in the country’s new 10-year power development plan “PDP8” that the deputy prime minister signed off last week, had kept market players guessing. For instance, up till end-2021, solar power instead of wind was supposed to lead the renewables charge in the rapidly developing economy. Vietnam’s industry and trade ministry hinted at a switch in March this year.

PDP8 is to guide electricity-related investments up until 2030, and provide an early snapshot of progress being made towards 2050. The scheme has been revised several times since 2021, and is finalised two years behind schedule. Vietnam’s parliament will still need to give the final assent to the US$135 billion plan.

Analysts say the plan provides greater clarity for power developers, but also pointed to realities that the government has had to adapt to.

Here are the key differences between the latest PDP8 document, and some of the early drafts from 2021.

Wind trumps solar

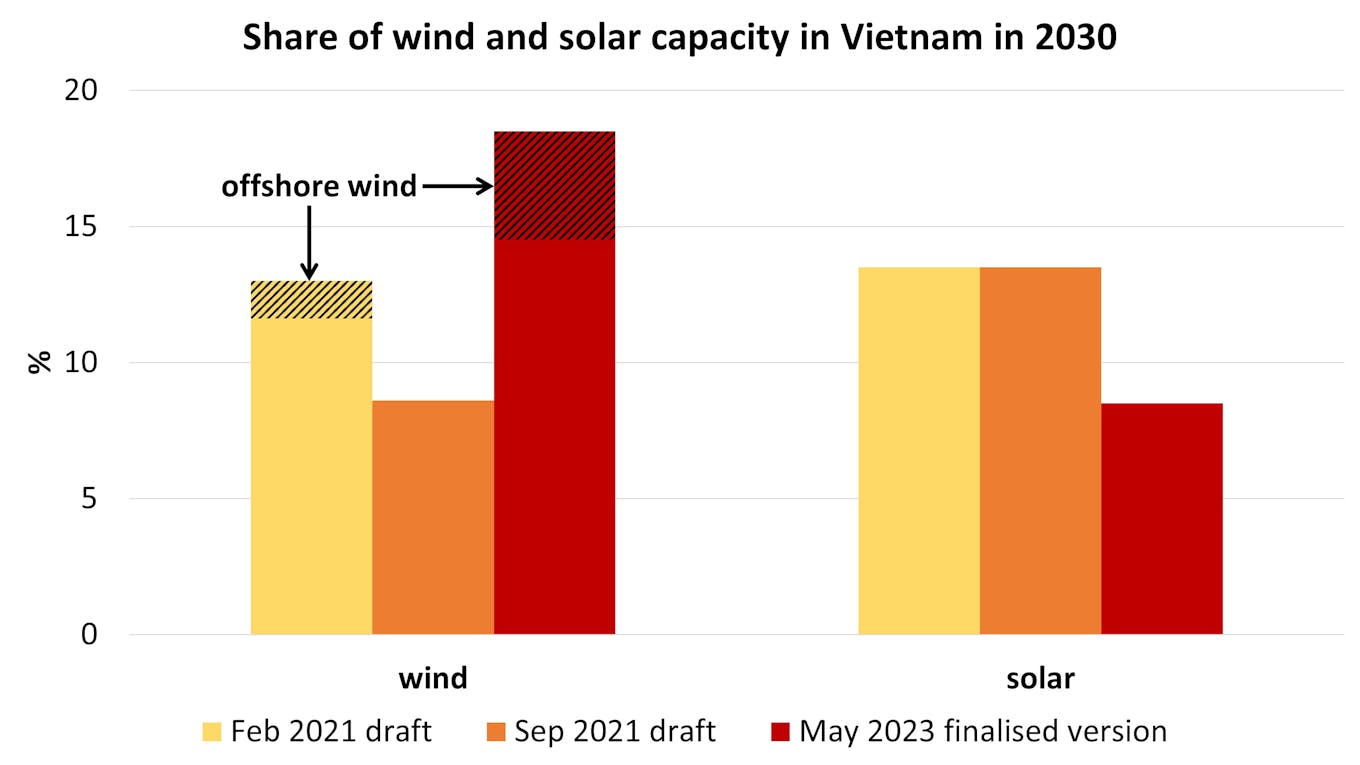

Percentage share of wind and solar capacity in Vietnam in 2030, according to various PDP8 drafts. Chart design by Eco-Business. Data: Vietnam government, Baker McKenzie.

PDP8 projects that there will be almost 28 gigawatts (GW) of wind power in Vietnam by 2030, contributing 18.5 per cent of the total generation capacity. Total installed wind power capacity is around 4.6GW today, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Early PDP8 drafts had indicated a falling interest in wind. In a draft released in September 2021, wind was to contribute just 8.5 per cent to the 2030 power mix.

Meanwhile, the total capacity of solar panels connected to the national grid is to be under 13GW by 2030, representing 8.5 per cent of total capacity, down from 18.6GW and 13.5 per cent in earlier drafts.

Instead, the Vietnamese authorities want people to install solar panels only for their own use. Half of all office buildings and houses should have rooftop panels by 2030, and there are no limits set for such small-scale use, PDP8 states. However, building owners cannot sell electricity to the national grid.

IRENA statistics show that Vietnam currently has 18.4GW of installed solar power in total, while the Vietnam government has said there was about 10GW of rooftop solar systems in operation near the end of 2021.

Vietnam has had a rocky experience scaling up solar power. The government had agreed to buy solar power from developers at a high price in 2018, leading to a building boom that strained power grids with highly variable electricity output. Some solar plants had to stop generating electricity even when the sun was out, leading to financial losses.

There are also solar power projects that have been delayed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, with talks over pricing and the date of commercial launch still ongoing.

Dr Oliver Massmann, a Vietnam-based partner at law firm Duane Morris who advises renewables developers, said the authorities’ decision to go slower on solar is to ensure that currently ongoing projects can first be implemented. He noted that some pipeline projects have been shifted until after 2030 if they intend to connect to the national grid, but can start earlier if they do not intend to.

Rooftop solar projects outside of the national grid still represent a huge market for project developers, Massmann said, noting that only about 5 per cent of available space has been used and that small projects of under 1 megawatt (MW) in capacity do not require licensing.

“You have huge office buildings in cities like Hanoi, Da Nang and Saigon on which [solar panels] can be built, so there is still huge potential [for solar power in Vietnam],” Massmann said.

Large batteries could absorb the variable electricity output of solar panels and ensure a steady flow of power into the national grid, but PDP8 only targets a low 300MW of battery capacity by 2030.

Grant Hauber, strategic energy finance advisor at US-based think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), said the main issue with batteries is their high cost, and that the 300MW target shows that their deployment in Vietnam over the coming years would be limited to a few experiments. Vietnam also does not have variable electricity pricing that responds to immediate supply and demand changes, a model that could make batteries more financially viable, he said.

Hauber added that wind power projects could be more manageable for the authorities as they take up less land and are easier to locate, but in any case the national grids need to be upgraded with higher-voltage systems to handle the variable power load.

Nguyen Lan Phuong, a partner at law firm Baker McKenzie, said wind power development could be prioritised now because it is less mature than the solar industry. While solar farms can be set up in months, wind turbine projects often need years for siting, regulatory clearance and construction, Nguyen noted.

Solar power is still expected to feature heavily in Vietnam’s long-term plans, with total capacity up to nearly 190 GW by 2050, equal to over a third of total power supply then, according to PDP8. Wind power will contribute another 30 per cent of electricity capacity by mid-century.

These plans show that “the priority of the Vietnamese government is on the use of diversified renewable energy sources for power production, in order to ensure energy security, increase the independence of the power industry and decrease the dependence on imported fuels”, said Nguyen.

She noted that PDP8 would cap carbon emissions from the power sector to under 31 million tonnes in 2050, lower than the 35 million tonnes the Vietnamese government has said is the threshold to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century.

Gas imports to replace coal

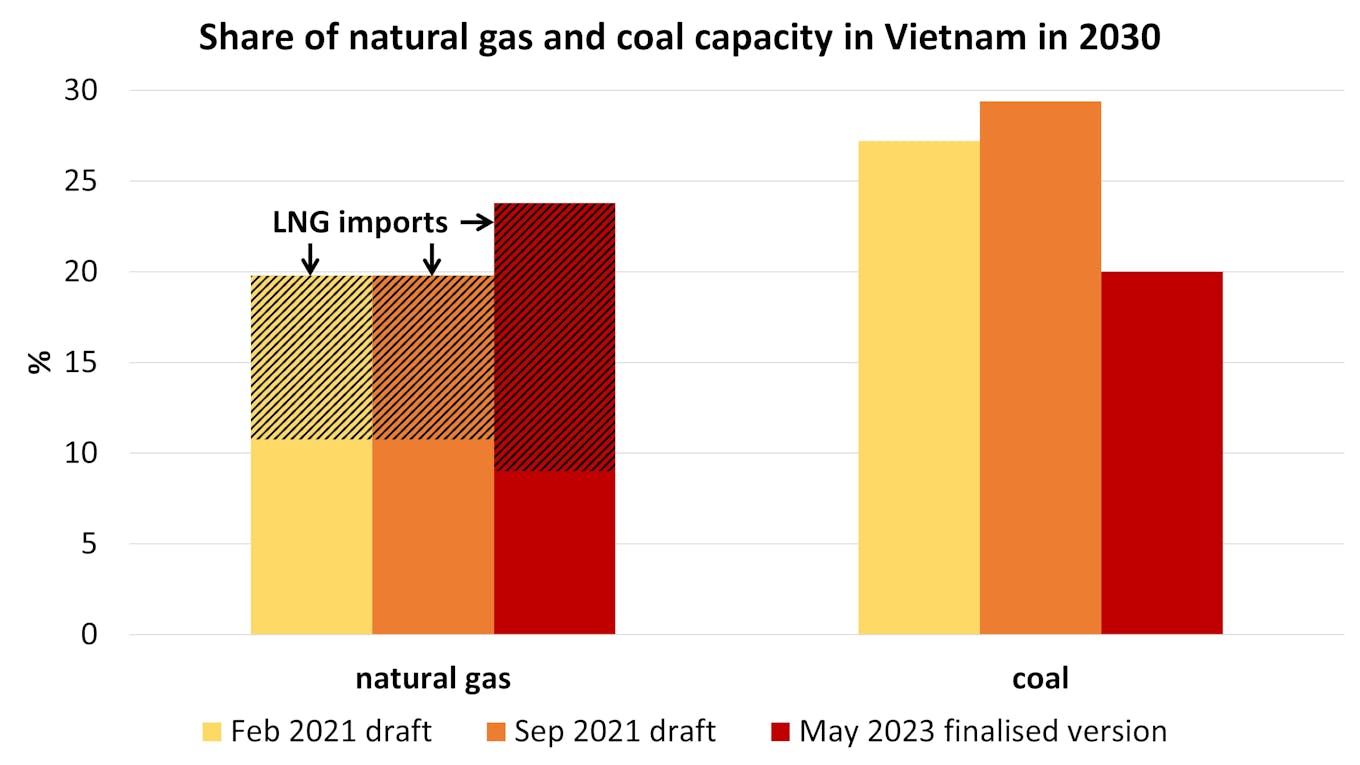

Percentage share of natural gas and coal capacity in Vietnam in 2030, according to various PDP8 drafts. Chart design by Eco-Business. Data: Vietnam government, Baker McKenzie.

PDP8 features a notable drop in the share of cheap but pollutive coal power in 2030, from around 30 per cent in previous drafts to 20 per cent. It pledges no new coal plants after 2030, and zero coal power generation by 2050.

In the meantime, coal plants in development will add about 7GW of capacity to the current 23GW in operation. The cheap but pollutive fuel currently contributes to a third of installed capacity in the country today.

Wealthy countries and donors pledged US$15.5 billion to help Vietnam wean off coal via a “Just Energy Transition Partnership” (JET-P) at the end of last year, though exact funding mechanisms are still being devised. The 2030 coal capacity envisaged in PDP8 roughly matches the 30.2GW peak pledged in the JET-P agreement.

Meanwhile, the proportion of imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Vietnam’s 2030 power mix is projected to be nearly 15 per cent, up from 9.1 per cent in an early PDP8 draft. The share of domestic natural gas will drop slightly from 10.7 to 9.9 per cent.

In absolute terms, the changes represent an addition of some 10GW of power capacity from gas by 2030, to 37GW in total. Vietnam’s gas power capacity in 2020 was around 7GW.

Vietnam, a natural gas producer, is a new entrant to the LNG-buying market, only having recently issued its first tender for the fuel. It has one LNG terminal, completed this year, and a handful in the works.

The drop in coal-fired energy could be a way Vietnam seeks funding from the JET-P deal, and the increase in LNG imports to ensure energy security, Massmann from Duane Morris said. Vietnam still has sizable domestic gas reserves, but the increase in demand is outstripping supply capabilities.

Vietnam may want to enter the LNG market quickly because other countries are already doing so in response to the fuel crunch brought on by the Russia-Ukraine war, Massmann added, pointing to how Germany has quickly built three floating LNG terminals.

“Everyone is banking on LNG, and so if Vietnam is not aggressive, they will not get [the fuel] anymore, and also the price could go up,” Massmann said.

But IEEFA’s Hauber said he does not see how Vietnam can scale up LNG power capacity that quickly, given how there has traditionally been protracted price negotiations for supply deals.

It is a “fair assumption” that foreign investors such as Japan and South Korea could contribute to Vietnam’s LNG push, and that the United States would want to export the fuel, but the market is still volatile, Hauber said. He pointed to LNG sellers reneging on contracts with Pakistan, which some believe was done to free up supply for the more lucrative European market.

Hauber added that swapping out coal for natural gas, a fossil fuel that produces less carbon dioxide emissions when burned, will not help Vietnam meet its 2050 net-zero emissions targets. Natural gas is predominantly methane – a much stronger greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide – and leaks along the supply chain could still cause climate heating, he said.

Nguyen from Baker McKenzie said the conversion of coal plants to use cleaner fuels like biomass and ammonia and the introduction of green hydrogen into gas plants can help Vietnam decarbonise electricity generation.

New fuels like ammonia and hydrogen do not feature in PDP8’s 2030 plans, but are mentioned in plans towards 2050.

More power sought

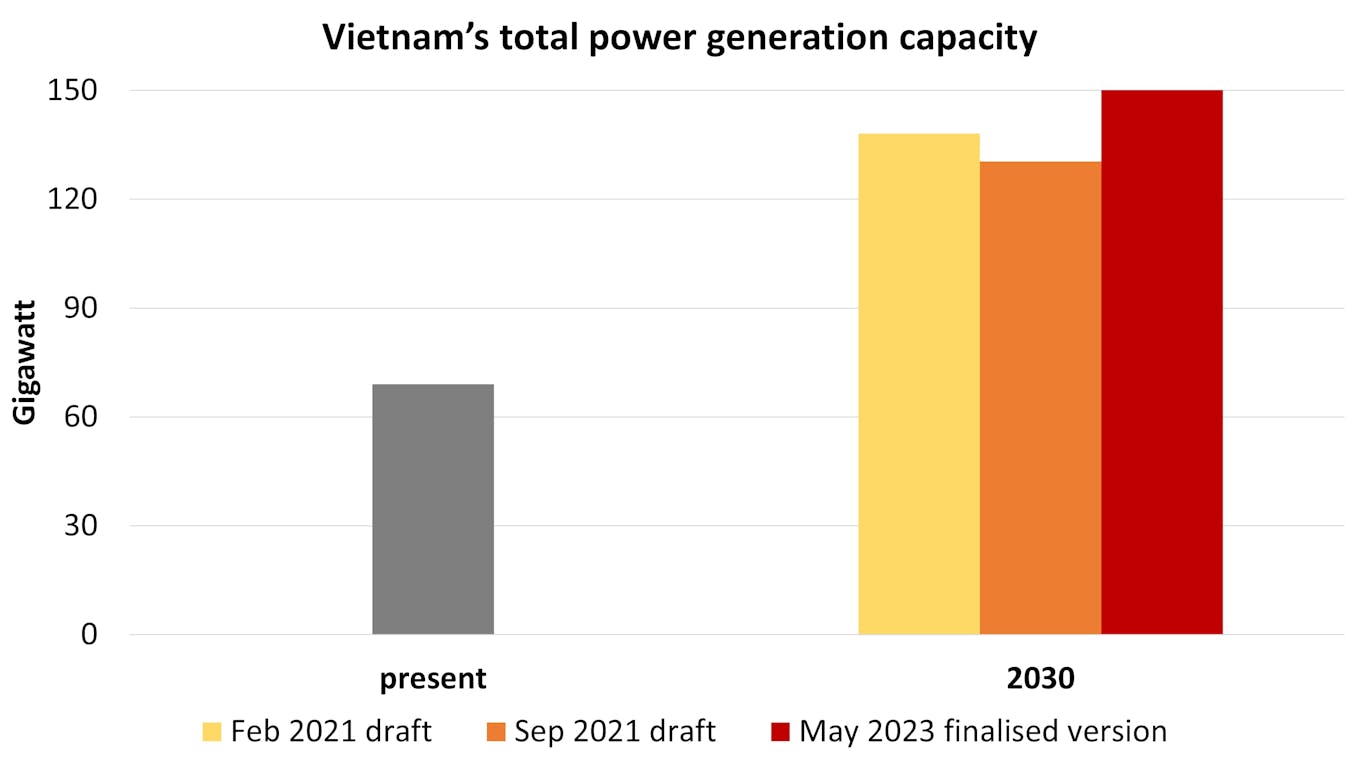

Vietnam’s total power generation capacity, present and 2030, according to various PDP8 drafts. Chart design by Eco-Business. Data: Vietnam government, Baker McKenzie.

Vietnam’s power generation capability in 2030 is expected to exceed 150GW, up from previous estimates that range from 130GW to 140GW. The country has 70GW of power capacity today.

PDP8 states that Vietnam’s energy strategies must help the regional manufacturing powerhouse achieve an average growth in gross domestic product of 7 per cent annually, roughly matching its pre-pandemic performance.

More people will also need electricity. Vietnam’s population is expected to cross the 100 million mark soon, and grow to about 104 million by 2030, according to the United Nations.

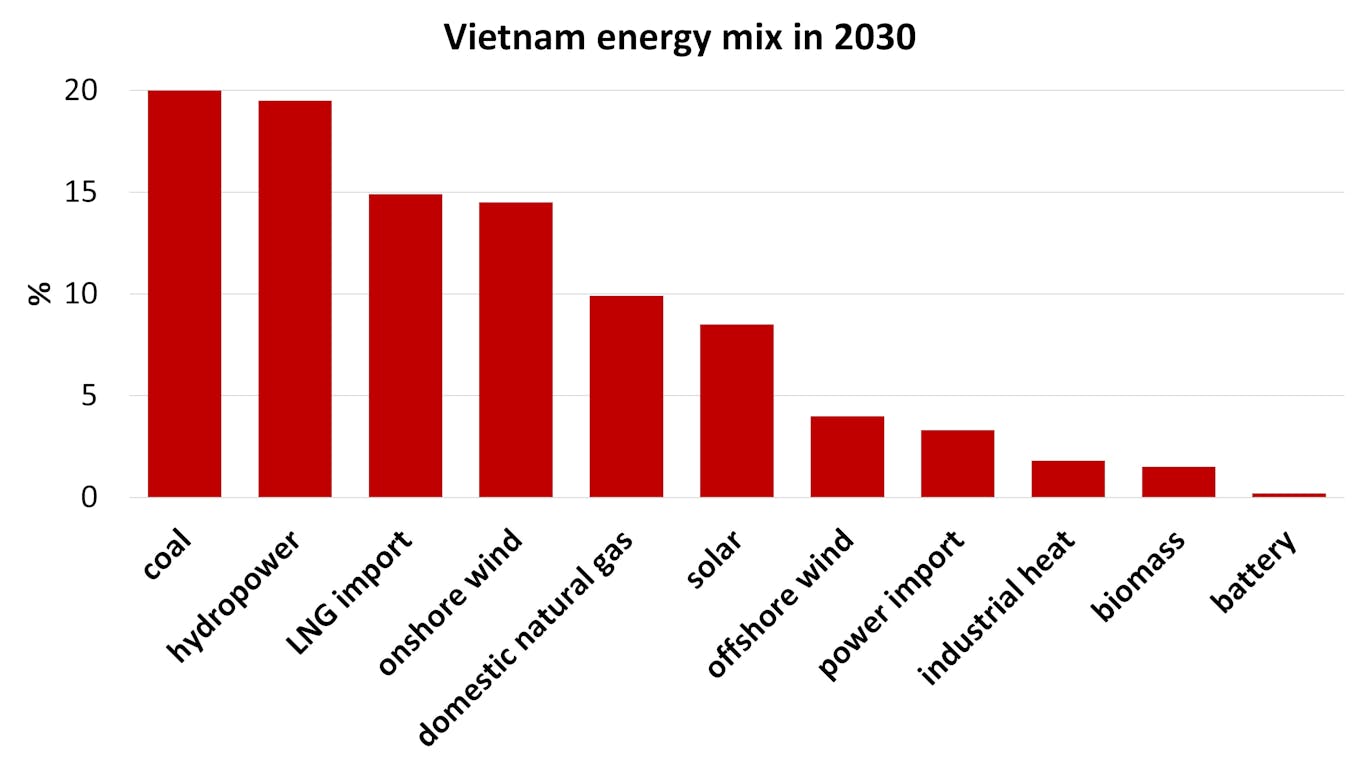

Other energy sources like biomass and power imports will play a small but growing role in the country’s electricity mix through to 2030. Hydropower, which accounts for 30 per cent of the electricity mix today, will continue to play a prominent role at just under 20 per cent in 2030. It appears unlikely that any power source will dip in absolute capacity in the coming years, despite growing calls by scientists and advocates to shed fossil fuels faster.

Vietnam energy mix in 2030, according to the latest PDP8 scheme. Chart design by Eco-Business. Data: Vietnam government.

PDP8 repeatedly stated that clean energy development will be contingent on international funding – especially from the JET-P agreement – as well as the technological and market readiness of new energy sources. The government indicated it is willing to move faster in areas such as biomass and offshore wind if conditions are favourable.

Hauber said PDP8’s near-finalisation is important, since there is now more clarity on what the authorities intend to focus on.

“Not everyone is going to be happy, the wind people are going to be happier than the solar people. But PDP8 narrows the universe of options so [developers] can concentrate on what the government is willing to support,” he said.

Massmann noted that PDP8 incorporates both energy security and decarbonisation considerations, and while late in publication, represents a “thought-through, well-drafted” plan.

The finalisation of PDP8 is one of the chief asks of project developers, which had sought greater clarity on rules in recent years. Outstanding matters include when and if the government will launch auctions for renewables projects, and the details for long-term power purchase agreements.