Humans are leaving a heavy footprint on the Earth, but when did we become the main driver of change in the planet’s ecosystems?

Many scientists point to the 1950s, when all kinds of socioeconomic trends began accelerating. Since then, the world population has tripled. Fertiliser and water use expanded as more food was grown than ever before. The construction of motorways sped up to accommodate rising car ownership while international flights took off to satisfy a growing taste for tourism.

The scale of human demands on Earth grew beyond historic proportions. This post-war period became known as the “Great Acceleration”, and many believe it gave birth to the Anthropocene — the geological epoch during which human activity surpassed natural forces as the biggest influence on the functioning of Earth’s living systems.

But researchers studying the ocean are currently feeling a sense of déjà vu. Over the past three decades, patterns seen on land 70 years ago have been occurring in the ocean. We’re living through a “Blue Acceleration”, and it will have significant consequences for life on the blue planet.

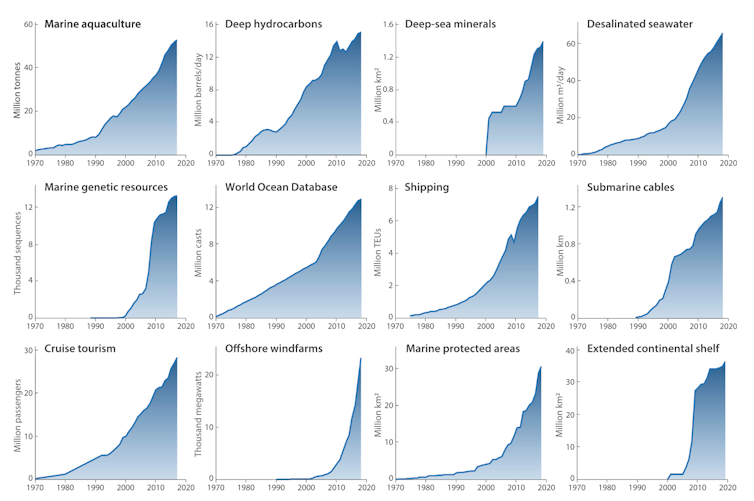

Human claims on ocean resources and space have increased rapidly in the last three decades. Image: Jouffray et al. (2020), Author provided

Why is the Blue Acceleration happening now?

As land-based resources have declined, hopes and expectations have increasingly turned to the ocean as a new engine of human development. Take deep sea mining. The international seabed and its mineral riches have excited commercial interest in recent years due to soaring commodity prices.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the price of gold is up 454 per cent since 2000, silver is up 317 per cent and lead 493 per cent. Around 1.4 million square kilometres of the seabed has been leased since 2001 by the International Seabed Authority for exploratory mining activities.

“

All of these interests are vying for the same ocean space, and their demands are growing.

In some industries, technological advances have driven these trends. Virtually all offshore windfarms were installed in the last 20 years. The marine biotechnology sector scarcely existed at the end of the 20th century, and over 99 per cent of genetic sequences from marine organisms found in patents were registered since 2000.

During the 1990s, as the Blue Acceleration got underway, the world population reached 6 billion. Today there are around 7.8 billion people. Population growth in water-scarce areas like the Middle East, Australia and South Africa has caused a three-fold growth in volumes of desalinated seawater generated since 2000. It has also meant a nearly four-fold increase in the volume of goods transported around the world by shipping since 2000.

Why does the Blue Acceleration matter?

The ocean was once thought — even among prominent scientists — to be too vast to be changed by human activity. That view has been replaced by the uncomfortable recognition that not only can humans change the ocean, but also that the current trajectory of human demands on the ocean simply isn’t sustainable.

Consider the coast of Norway. The region is home to a multi-million dollar ocean-based oil and gas industry, aquaculture, popular cruises, busy shipping routes and fisheries. All of these interests are vying for the same ocean space, and their demands are growing.

A five-fold increase in the number of salmon grown by aquaculture is expected by 2050, while the region’s tourism industry is predicted to welcome a five-fold increase in visitors by 2030. Meanwhile, vast offshore wind farms have been proposed off the southern tip of Norway.

The ocean is vast, but it’s not limitless. This saturation of ocean space is not unique to Norway, and a densely populated ocean space runs the risk of conflict across industries. Escapee salmon from aquaculture have spread sea lice in wild populations, creating tensions with Norwegian fisheries. An industrial accident in the oil and gas industry could cause significant damage to local seafood and tourism as well as the seafood export market.

More fundamentally, the burden on ocean ecosystems is growing, and we simply don’t know as much about these ecosystems as we would like. An ecologist once quipped that fisheries management is the same as forestry management. Instead of trees you’re counting fish, except you can’t see the fish, and they move.

Exploitation of the ocean has tended to precede exploration. One iconic example is the scaly-foot snail. This deep sea mollusc was discovered in 1999 and was on the IUCN Red List of endangered species by 2019. Why?

As far as scientists can tell, the species is only found in three hydrothermal vent systems more than 2,400 metres below the Indian Ocean, covering less than 0.02 square kilometres. Today, two of the three vent systems fall within exploratory mining leases.

What next?

Billionaires dreaming of space colonies can dream a little closer to home. Even as the Blue Acceleration consumes more of the ocean’s resources, this vast area is every bit as mysterious as outer space. The surfaces of Mars and the Moon have been mapped in higher resolution than the seafloor.

Life in the ocean has existed for two billion years longer than on land and an estimated 91 per cent of marine species have not been described by science. Their genetic adaptations could help scientists develop the antibiotics and medicines of tomorrow, but they may disappear long before that’s possible.

The timing is right for guiding the Blue Acceleration towards more sustainable and equitable trajectories. The UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development is about to begin, a new international treaty on ocean biodiversity is in its final stages of negotiation, and in June 2020, governments, businesses, academics and civil society will assemble for the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon.

Yet many simple questions remain. Who is driving the Blue Acceleration? Who is benefiting from it? And who is being left out or forgotten?

These are all urgent questions, but perhaps the most important and hardest to answer of all is how to create connections and engagement across all these groups. Otherwise, the drivers of the Blue Acceleration will be like the fish in the ecologist’s analogy: constantly moving, invisible and impossible to manage — before it is too late.

Robert is a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. This article was originally published on The Conversation.