When China launched its five-year Air Pollution Action Plan in 2013 it was recognition that the country’s smog problem needed to be brought under control. As the plan enters its final year, official data indicates that long term progress is being made to improve air quality overall.

Yet the continued occurrence of major air pollution events shows that there’s still a long way to go.

Making progress

The concentration of fine particles is a key measure of air quality in China. Particles of 2.5 micrometres in diameter or smaller (PM2.5) are of particular concern because they can lodge in the lungs and brain, and enter the blood stream. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an average annual concentration of 10 microgrammes per cubic metre (μg/m3) or higher of PM2.5 is unsafe, with long term exposure to higher concentrations increasing the risk of early death.

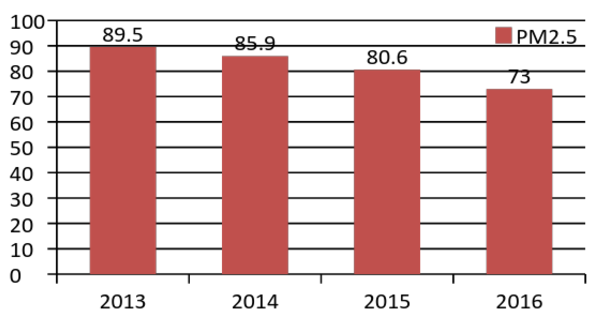

China’s targets state that three key city clusters – Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei in the north, and the Pearl and Yangtze deltas in the southeast – must lower PM2.5 levels by 15 per cent, 25 per cent, and 25 per cent respectively by the end of 2017. In Beijing, specifically, the average annual concentration of PM2.5 must be 60 μg/m3 or less, compared to 89.5 μg/m3 in 2013.

Meeting the targets presents a significant challenge. In 2013, when 74 cities started publishing data on PM2.5 levels, 71 failed to meet WHO’s laxest “interim” target of an annual average of 35 μg/m3. The government claims that air quality has improved since then. China’s environmental protection minister Chen Jining said at a press conference at the start of the year that air quality had improved 30 per cent on 2013 in the three city clusters, indicating that some targets were being met early.

This claim is backed up by an evaluation of air quality management by the China Clean Air Alliance, published in August 2016. It showed that a number of cities in the targeted clusters had hit 2017’s target by the end of 2015, two years ahead of schedule. Data from China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) also showed that the number of cities achieving WHO’s interim target in the first half of 2016 had risen from 4 per cent in 2013, to almost 25 per cent.

“It looks like the targets can be met,” said He Kebin, head of Tsinghua University’s School of the Environment.

While optimistic, Kebin is also quick to note that Beijing’s target of 60 μg/m3 will be difficult to meet. The average level in the city in 2016 was 73 μg/m3, notwithstanding the recent seasonal spike that saw the level shoot up to over 1,000 μg/m3 for a period in December.

Success will require repeating the previous two year’s reduction rate in a single year; an almost impossible task.

Changes in PM2.5 levels in Beijing, 2013-2016

Data source: Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau

A tough task for Beijing

Air pollution became a more salient political and environmental issue when the US Embassy in Beijing began publishing its readings on social media in 2008. Prior to this, there was little awareness of PM2.5 levels. Although the capital does not have the worst air quality in the country, the issue does get more attention because it is home to the offices of media organisations and international bodies.

Beijing has seen consistent drops in annual PM2.5 levels over the past three years, initially by just 4 per cent, but more recently by as much as 10 per cent. Levels of pollution in the capital are expected to be 66 μg/m3 in 2017, according to data from the Beijing Protection Bureau, some way off the target of 60 μg/m3 (the national target applied to all cities).

Despite the reductions in average levels of air pollution, major short term pollution events continue to happen, including one that triggered Beijing’s first official “red alert” in December 2015, and another last December. On the first day of 2017, large areas of Beijing saw PM2.5 concentrations reach 500 μg/m3. This threshold triggers the toughest emergency measures, including banning polluting vehicles and closing highly polluting industry.

Chen Jining remains hopeful that the targets can be met. He said that Beijing’s economic structure has improved and the city is now in a better position, alongside Tianjin and Hebei, to take more direct action to tackle pollution.

In July, the MEP and Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei governments jointly published a set of air pollution measures to be taken in 2016 and 2017, which were an attempt at those more specific measures. These included the continued closure of small, unofficial industrial parks that are home to polluting factories on the outside of the cities; replacing coal stoves used by villagers; and reducing the number of polluting vehicles.

Winter arrives in Zhugeying, a village in the Beijing district of Daxing. The sign refers to a ban on the sale or bringing in of coal. There is a coal control point nearby, staffed by officials who visit local homes to check if they are burning coal. (Photo: Zhang Chun)

Beyond the action plan

Ensuring continued reductions in air pollution from 2018 onwards will require closer attention to reducing source emissions. Catherine Witherspoon, former head of California’s Air Resources Board, has compared China’s current approach with that of California’s long term plans of several decades earlier, and finds that China is still leaning on “emergency” measures.

This is apparent in the frequent use of “government orders”, which are short term interventions to curb emissions. For example, polluting industries in Hebei, which supplies one eighth of the world’s steel, were ordered to shut down for 45 days in November.

According to a 2013 report by the Chinese Academy of Engineering, emergency measures taken during red alerts account for about 20 per cent of the improvement in Beijing’s PM2.5 levels.

“But you can’t close them forever,” says Witherspoon. While she believes that China can hit its 2017 air pollution targets, she holds that five years is too short a timeframe to bring about a stable industrial and energy transition or sustainable social development. She advocates a more targeted approach centred on technology upgrades.

Emergency shutdowns exact a social cost, too. Elaine Chang, former head of California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District said at the Blue Tech Awards that the key to success in dealing with air pollution is a patient approach that takes account of the social costs resulting from wages falling and lost industrial jobs, which must be limited as far as possible.

He Kebin expects that China will meet the WHO interim target faster than the US did, which took 50 years. But despite the rapid progress, it will still take a decade or more to catch up, he says.

This story was originally published by chinadialogue under a Creative Commons’ License and was republished with permission.