The Philippines ended 2023 on a sustainability high note by securing a seat on a first-ever global fund to help poor countries deal with the adverse impacts of climate change at COP28.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The coal-dependent country also showed intent to move away from fossil fuels by attracting 3 GW (gigawatts) of new renewable energy investment from the private sector in 2023; more than the total clean energy installed over the past seven years.

A law which requires big companies to take responsibility for their plastic footprint went into full swing last year in the archipelagic nation, which is the world’s largest marine plastic polluter according to a 2023 study.

However, these sustainability milestones came in a year fraught with anti-mining protests, rising electricity prices as temperatures soared, and cities drowning in plastic waste.

As we enter into the new year, here are some policies needed for the Philippines to move the needle on climate action.

1. Additional 221 GW in renewable energy capacity to help drive down electricity prices

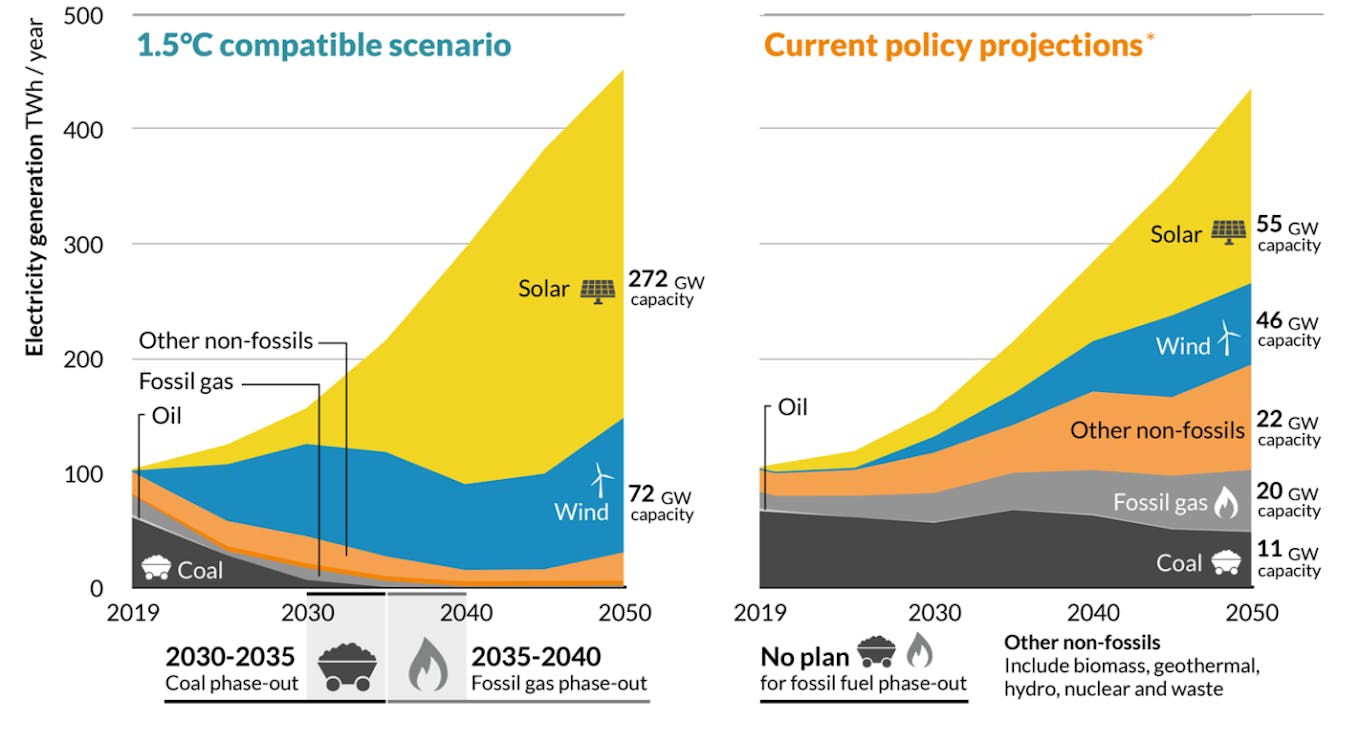

The government’s current policy projection includes 123 GW of renewable energy capacity (55 GW of solar, 46 GW of wind, 22 GW of other renewables), with no plan for a fossil fuel phase out by 2050. In order to align with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C warming limit, the country needs to add 221 GW of capacity to reach 344 GW of mostly solar energy, and phase out coal and natural gas by 2040. Image: Climate Analytics

The government’s green energy auction programme last year resulted in 3 GW of renewables to be installed by 2025, as one of the policies put in place to help the country achieve its goal of 35 per cent of its energy mix powered by clean energy by 2030.

This is commendable but does little to align our country with the 1.5°C warming limit set out in the Paris Agreement as existing solar and wind capacity in the Southeast Asian nation is currently just 2 GW.

The current policy projected in the Philippines’ national energy plan is 123 GW of mostly solar and wind capacity by 2050. It would need to reach 344 GW over the same period to transition its electricity system to clean power and meet the Paris 1.5°C goal, according to a study by German-based research institution Climate Analytics released in November.

This additional capacity will generate 152 terrawatt hours (Twh) of electricity, which is equivalent to the electricity needed to power almost 13 million homes in one year.

The current policy projection has no strategy to phase out fossil fuels. In fact, the latest draft energy development plan presented to private investors in September includes the need for additional coal and gas sources.

The authorities will argue that continued investment in fossil fuel sources is necessary amid declining reserves from the Malampaya natural gas field and rising electricity demand, as the country is poised for another hot summer feared to compromise a national grid already in need of an upgrade.

Just last week, the National Grid Corp. of the Philippines (NGCP) came under fire for the massive outage in Western Visayas during the New Year’s Day holidays as it failed to prevent a collapse of the power transmission system that caused hardship for local communities, crippled businesses and endangered health care systems in the region.

Energy firms have promised adequate supply throughout the nation over the coming year, but Aboitiz Power Corp president Emmanuel Rubio said the key question is how much electricity will cost.

Filipinos pay more for electricity than anywhere in Southeast Asia, except for Singapore.

But the Climate Analytics research shows that as the share of renewables increases in the power mix, so does their contribution to the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) – or the price at which the electricity generated should be sold for the system to break even at the end of its lifetime; adding more stability to prices.

By contrast, fossil fuels make electricity prices more volatile due to the country’s reliance on imported coal and gas.

As long as we are forced to rely on electricity from fossil fuels, high electricity rates and unstable power will always be our reality.

2. “Ethical” clean energy

Early construction of wind turbines sighted within the Masungi Georeserve. Image: Billie Dumaliang

It isn’t just mining that faces complex ethical issues in the clean energy transition. Last year saw an increase in the planned construction of wind farms in protected areas.

Rizal Wind Energy Corp, operating under Singapore-based renewable energy firm Vena Energy, was found to be eyeing the Masungi Georeserve for a wind farm development. It is the latest setback faced by the sanctuary, an important nature reserve and wildlife sanctuary about 30 miles from Manila.

Transporting and erecting heavy wind turbine towers and blades threatens the area as it requires forests to be cleared to build access roads.

“Once open and accessible, the roads will later make way for the uncontrolled and continuing entry of people and encroachment and degradation of the rest of the karst landscape and ecosystems. Its inaccessibility and harsh terrain have been the landscape’s biggest deterrent versus widespread and large-scale depredation. Put in roads and you sign its death certificate,” said Billie Dumaliang, advocacy officer and trustee at the Masungi Georeserve Foundation.

Wind turbines are known to be fatal for bats and birds, especially raptors. Masungi is home to the endangered Philippine hawk-eagle, the serpent eagle and the first record of flying foxes in the Rizal province, as well as 30 species of bats and 100 species of birds.

Aside from Masungi, the Nabas Wind Power Project unveiled plans for expansion within the Northwest Panay Peninsula Natural Park in the Visayas region last year, that is feared to cause deforestation, extensive road construction, and erosion.

It may also cause the siltation of several rivers and streams that may contaminate the supply of water for lowland communities and in the nearby world-renowned Boracay Island.

While our clean energy transition is essential, equitable as well as ethical solutions must be something policymakers consider in the coming year.

3. Investment in MRFs

Last year marked the first year of implementation of the extended producer’s responsibility act, which requires big companies to recover the plastic they produce and sell.

Under the law, some of the country’s largest corporate polluters, with total assets worth more than US$1.8 million, are mandated to recover at least one-fifth of the plastic they produced in 2023.

Companies can either recover their own waste or go through waste diverters like waste picker cooperatives, junk shops or materials recovery facilities (MRFs) to recover, recycle or dispose of their plastic waste for a fee.

An MRF is a specialised plant that segregates material for recycling and prepares it for marketing to end-user manufacturers. They convert biodegradable waste into fertiliser, which is then recycled or sold to junk shops, with residual refuse sent to sanitary landfills.

There were 11,000 MRFs in the country as of 2021, catering to around 40 per cent, or 16,418 out of the total 42,046 barangays, based on the latest data from the National Solid Waste Management Commission (NSWMC). Facilities are generally constructed out of local funds, grants, and loans.

Corporates can hasten the progress of the EPR if they can help municipalities invest in infrastructure, given that the success of the law relies on how the various waste management facilities in the archipelago collect refuse.

4. Leveraging on being a board member of the loss and damage fund

Despite the criticism around Philippine head of delegation Toni Yulo-Loyzaga for not articulating a stronger stance against fossil fuels at COP28 compared to her predecessors, her team must be commended for securing the country a seat on the loss and damage fund.

The country will represent the Asia Pacific Group as a full member for 2024 and 2026 and as an alternate member in 2025, sharing the term that year with Pakistan.

Loyzaga said that having a seat on the board would give the Philippines an opportunity to influence the decision-making on who gets to have access to the fund, and how fast.

It is no secret that climate funding takes a long time to reach recipient countries.

I learnt from Rachel Herrera, commissioner of the Climate Commission of the Philippines, in a previous interview that it takes at least one to two years to carry out the entire process, from project proposal to its approval, until a member state finally gets the money.

The commission used to be the gatekeeper for accessing and receiving climate funds before the department of finance took over in 2021.

Climate finance may also be stalled if the board of the financial mechanism does not meet often, like how the Green Climate Fund, a fund set up in 2010 to disperse adaption finance to developing countries, only convenes three times a year at its headquarters in South Korea.

The entire process of accessing climate finance then becomes a competition among developing countries over who gets most of the pie. With the Philippines also vying to host the global fund, our typhoon-weary nation might finally play the role it deserves after decades of pushing for climate justice for vulnerable countries.