More and more countries, already representing about 70 per cent of the world economy, are setting climate neutrality targets. Hundreds of corporations, including the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, have pledged to become “net zero” by 2050 or earlier, and over 1,000 corporations have embraced science-based targets to measure carbon reductions.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This outburst of public declarations and pledges signifies a promising new alignment of ambitions to face the climate crisis. But declarations of good intentions by themselves are not going to lead to the required timely actions. In fact, despite the growing popularity of voluntary commitments, especially since the Paris Agreement of 2015, average carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmospheres have kept growing. They exceeded 410 parts per million in 2019 and kept rising in 2020 despite the Covid-19 lockdown, reaching a new record of 416 parts per million in February 2021.

Mitigating climate change is largely about accelerating the transformation of the energy systems that power and sustain our modern lives. The burning of fossil fuels accounts for about 80 per cent of the emissions that cause global warming. Growing the share of renewable sources of energy for producing electricity, electrifying all segments of the economy and employing low carbon technologies is possible in principle. But despite technological breakthroughs and the growing cost competitiveness of renewables, the current pace of change is still far too slow. According to statistics on recent primary energy consumption, the share of renewable sources now stands at about 5 per cent of primary energy. If all non-CO2-emitting sources – renewables, hydro and nuclear - were included, that share would stand at 16 per cent.

Organisations such as the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the World Resources Institute (WRI) estimate that the share of renewables must grow exponentially, and the share of fossil fuels decreased accordingly. The overall estimate is that the level of ambition needs to be roughly tripled to align with the 2°C limit and must be increased around fivefold to align with the 1.5°C limit.

Such a massive systems change cannot be achieved by public sector actions alone. In the case of the European Union, for example, it is estimated that in order to achieve the 55 per cent emission reduction target by 2030, €350 billion (US$294 billion) more need to be invested annually in the period from 2021 to 2030 than the amount invested in the period from 2011 to 2020. Public funding can help kickstart such a massive investment, but most of it will have to come from the private sector. By using 37 per cent of the €750 billion NextGenerationEU funds, as proposed by the EU Commission, €277 billion will be spent directly on the European Green Deal objectives, contributing about 8 per cent to the additional investment needs for the next decade. The situation is similar in the US. The huge infrastructure proposal by President Biden - even if fully implemented - would amount to only one eighth of the estimated required investments to stave off the worst projected dangers of a warming climate.

“

Declarations of good intentions by themselves are not going to lead to the required timely actions.

It is obvious that the full potential of the private sector needs to be activated in order to realise investments of such magnitude. This in turn can only be accomplished if framework conditions are adjusted and if CO2 is priced high enough to establish the business case for decarbonisation.

Establishing the business case for decarbonisation is the key to bringing about the systemic change needed to unleash the resources and creativity of the private sector. Much has been said and written about the failure to price emissions - British economist Nick Stern called climate change “the greatest market failure the world has seen” - and in principle there is broad understanding that “we cannot solve the climate crisis without effective carbon pricing”, as Janet Yellen, US Secretary of the Treasury, said at her confirmation hearing.

As illustrated in the report “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2020”, there are some 61 carbon pricing initiatives either implemented or scheduled within 46 national and 32 subnational jurisdictions. The recent results of the largest such scheme, the European Emissions Trading Systems (EU ETS), are encouraging. Greenhouse gas emissions covered by the scheme (power and heat generation and emission-intensive industries) have decreased by 33 per cent since 2005, with significant reductions especially in 2018 and 2019.

However, overall progress is slow. As of today, only about 22 per cent of global emissions are covered by carbon pricing initiatives and less than 5 per cent are subject to high enough levels. About half of the emissions are priced at less than US$10 per ton - with the global average price standing at US$2 per ton! Worse, subsidies for fossil fuels, estimated at US$478 billion in 2019, are more than ten times higher than revenues from carbon pricing (US$45 billion in (2019). If the indirect costs were to be included in the “perverse subsidies” for fossil fuels, this amount would be about US$5 trillion per year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

As the world is preparing for the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, there is now an opportunity to get serious with climate policies. We are only one investment cycle away from 2050 and we need to get the policies right - and right now. Policy makers have it in their hands to change the framework conditions by establishing effective carbon pricing that will unlock the needed investments.

A promising new initiative, Call on Carbon, aims to encourage policy makers to do so. The initiative was born in the Nordic countries. Carbon pricing has already been successfully introduced in these countries and has led to major shifts away from high-emitting activities toward cleaner and future-oriented technologies. Supported by business leaders and civil society actors, the Call on Carbon asks governments to:

- Back their net-zero targets with effective, robust, reliable and fit-for-purpose carbon-pricing instruments consistent with the Paris agreement in order to establish cost-efficient paths to reach net-zero emissions.

- Align carbon-pricing instruments to create stable and predictable investment environments.

- Finalise the rules for international market mechanisms under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement in order to support cost-effective mitigation efforts, create a level playing field and minimise carbon leakage.

It is hoped that many more private sector actors will join the Call on Carbon and encourage policy makers to be bold on carbon pricing. Unlike the many previous carbon pricing advocacy efforts that showed limited success, this time around the chances for getting heard are better - for several reasons:

First, the urgency to accelerate climate mitigation is better understood in major capitals around the world today. Governments can no longer postpone climate action or get away with cosmetic changes. The climate crisis is already upon us. Especially young people are rightly demanding bolder actions. Moreover, crisis situations lower barriers against change. As governments are employing trillions of US dollars to recover from the Covid-19 crisis, they have an opportunity to change the framework conditions for markets.

Second, as more robust climate action is becoming inevitable, decarbonisation and digitalisation of economies are fast becoming pillars of competitiveness. The inevitability of carbon reduction as a currency of the future should motivate policy makers and the private sector alike.

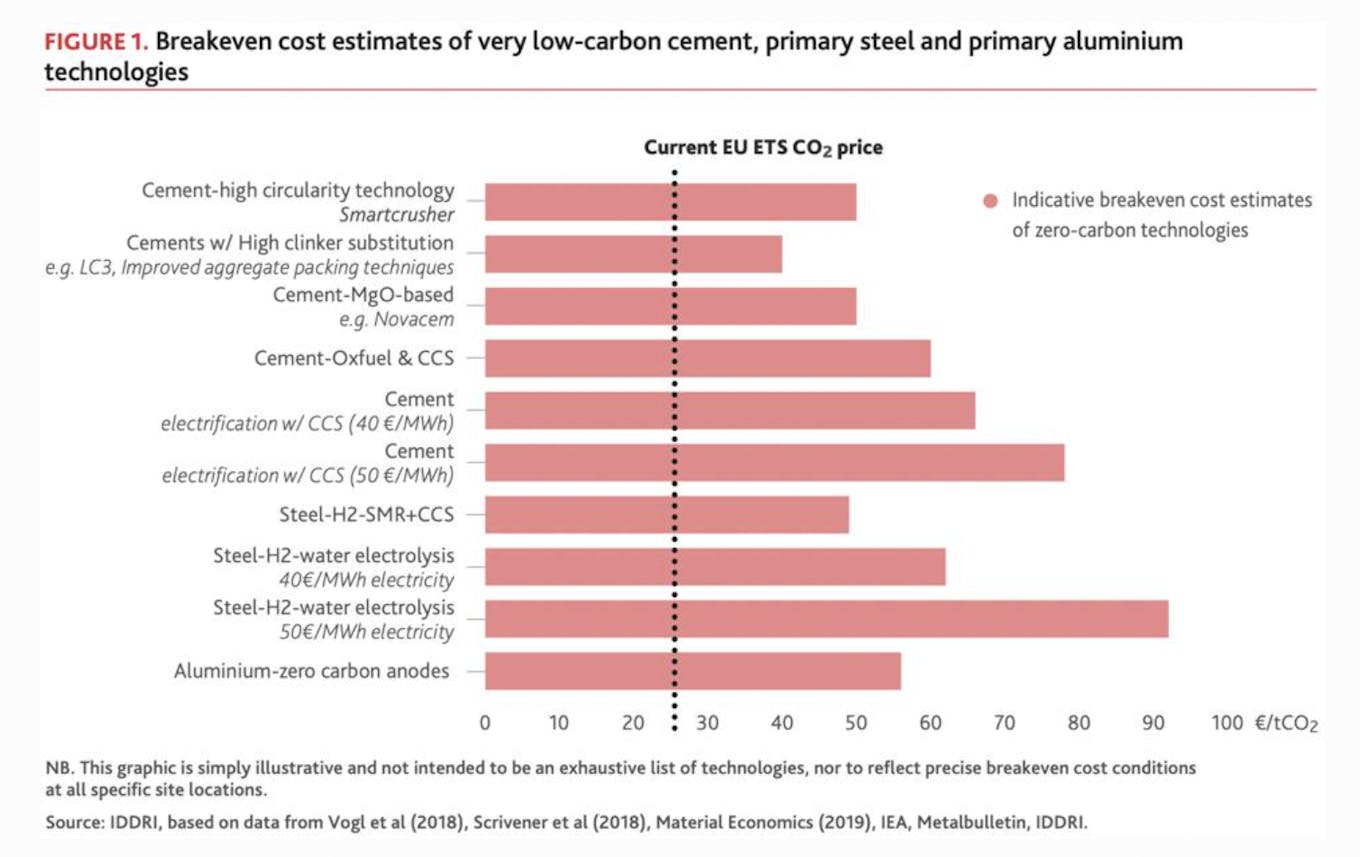

Third, thanks to technological progress and applications at scale, the cost of clean technology, such as solar and wind power generation, batteries, electrolysers and the production of low carbon materials, is falling rapidly. According to estimates by the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI), the break-even CO2 price for very low-carbon cement, primary steel and primary aluminum would be €50 to €90 per ton, with electricity costs between €40 to €50 per megawatt-hour. According to a Swedish study, this would increase the retail price of a car by only about €100 to €125.

Breakeven cost estimates of very low-carbon cement, primary steel and primary aluminum technologies. Source: IDDRI

Fourth, some environmental advocacy groups have been reluctant to support market instruments, fearing that these instruments could be used to undo performance standards for industries or further disadvantage low-income populations. But the evidence from existing carbon pricing schemes, such as those implemented in Nordic countries, show that both approaches can and should be employed simultaneously. Moreover, revenues from carbon pricing can be earmarked to offset any disadvantages to low-income populations.

With the upcoming COP26, this year is a potential turning point, offering policy makers to think big and to act accordingly. Phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and establishing an effective price for carbon is an essential and long overdue measure to mitigate climate change. The United States, China and the European Union are well positioned to demonstrate genuine leadership.

This article has been written in cooperation with Jouni Keronen, chief executive officer of the Climate Leadership Coalition