COP28 was interesting. For the first time it called for the world to move away from all fossil fuels, and in the same breath gave a nod to natural gas as a transition fuel.

The juxtaposition of those two statements is both jarring and contradictory. While there has been controversy around this, the transition fuel narrative has been prominent since the early 2000s. The fact that it needed some form of recognition at a global climate event seems curious.

Gas is portrayed as a cleaner fossil fuel because, when combusted, it emits half as muchcarbon than coal or oil. This is a constant narrative, not only espoused by industry but also used as justification in pro-gas policymaking and investment decisions.

However, the inconvenient truth usually omitted is that natural gas also emits methane—a more potent greenhouse gas that has a warming effect at least 80 times worse than carbon in the short term. Recognising gas as a transition fuel seems counterintuitive for a world that is chasing a 1.5C global warming limit by 2050.

As such, it feels like COP28 has missed the fine print and essentially turned a blind eye to some very important facts about gas. Why could this be?

Experts discredit gas

The global electrification push is chief amongst the drivers for declining oil and gas demand. This is not just a push by climate experts; financial institutions are also advocating for it. COP28 resulted in a new global target to triple renewable energy generation and double energy efficiency by 2030. The summit also witnessed an oil and gas pledge to accelerate climate action, which includes investing in renewable energy, low-carbon fuels and negative emissions technologies, enhancing transparency in greenhouse gas emissions and their reduction. Some of these dynamics have seen investors starting to view oil and gas as a sunset industry.

In anticipation of waning investor interest, it starts to make sense that the industry would seek ways to prolong its lifespan. If global vehicle sales – the driver of primary oil consumption – is any indicator, then the boat may have sailed for the oil sector in particular.

Gas may still see itself as having a chance. However, a 2022 paper published by the global authority on energy analysis and policy recommendations, the International Energy Agency (IEA), openly discredited the credentials of gas as a transition fuel, for the first time. It found that when gas is at its highest use, based on stated policies, global demand for the fuel would rise by less than 5 per cent between 2021 and 2030 and then plateau through to 2050.

The IEA’s 2023 outlook was no better. It found that global demand for coal, oil and gas would peak before 2030—less than six years from today. That is much sooner than what the gas majors were projecting.

Other crucial datapoints, coupled with the IEA’s unenthusiastic gas demand projections, signal the gas industry’s declining access to affordable future capital and explains their obsession with the “transition” label.

Green finance deals, of which 58 per cent were earmarked for renewable energty, overtook oil, gas and coal-related financing in the first half of 2023. This followed the US$1.1 trillion of green investment in 2022, which roughly equalled the amount of coal, oil and gas investments combined.

Also in the first half of 2023, sustainability-themed bonds globally crossed the US$4 trillion mark and their volumes have been climbing year-on-year. Gas projects were not widely backed by these bonds.

As debate continues about whether sustainable or green bond instruments offer any borrowing cost advantage over conventional debt, a study found that they can – by up to 8 basis points, in fact. Overwhelming investor interest has consistently dwarfed the supply of green bonds, also leading to lower financing costs for green projects.

However, there are geographical nuances around cost savings from early 2000 to 2021. For example, in China, the cost of debt for oil and gas production is generally higher than that of renewable. The same can be observed in Europe. In North America, however, oil and gas production has a lower cost of debt compared to reneable, which is no surprise given that up until the Inflation Reduction Act was approved in the US in August 2022, the policy landscape was much friendlier towards the oil and gas sector.

These signs of growing global interest in financing clean energy projects, an expanding sustainable finance market, and a declining cost of finance for renewable energy, may have spooked gas developers about their place in global energy systems.

No place in Asia’s sustainable finance taxonomies

The power sector globally is a key gas consumer. Asian markets appear more attractive to gas producers as the region will need some gas to meet its immediate and burgeoning energy demands, amid pressures to transition away from coal. However, while there could be a role for gas to play in their net-zero strategies, the logic as to why gas should have a place in sustainable finance taxonomies and benefit from potentially lower financing costs does not hold.

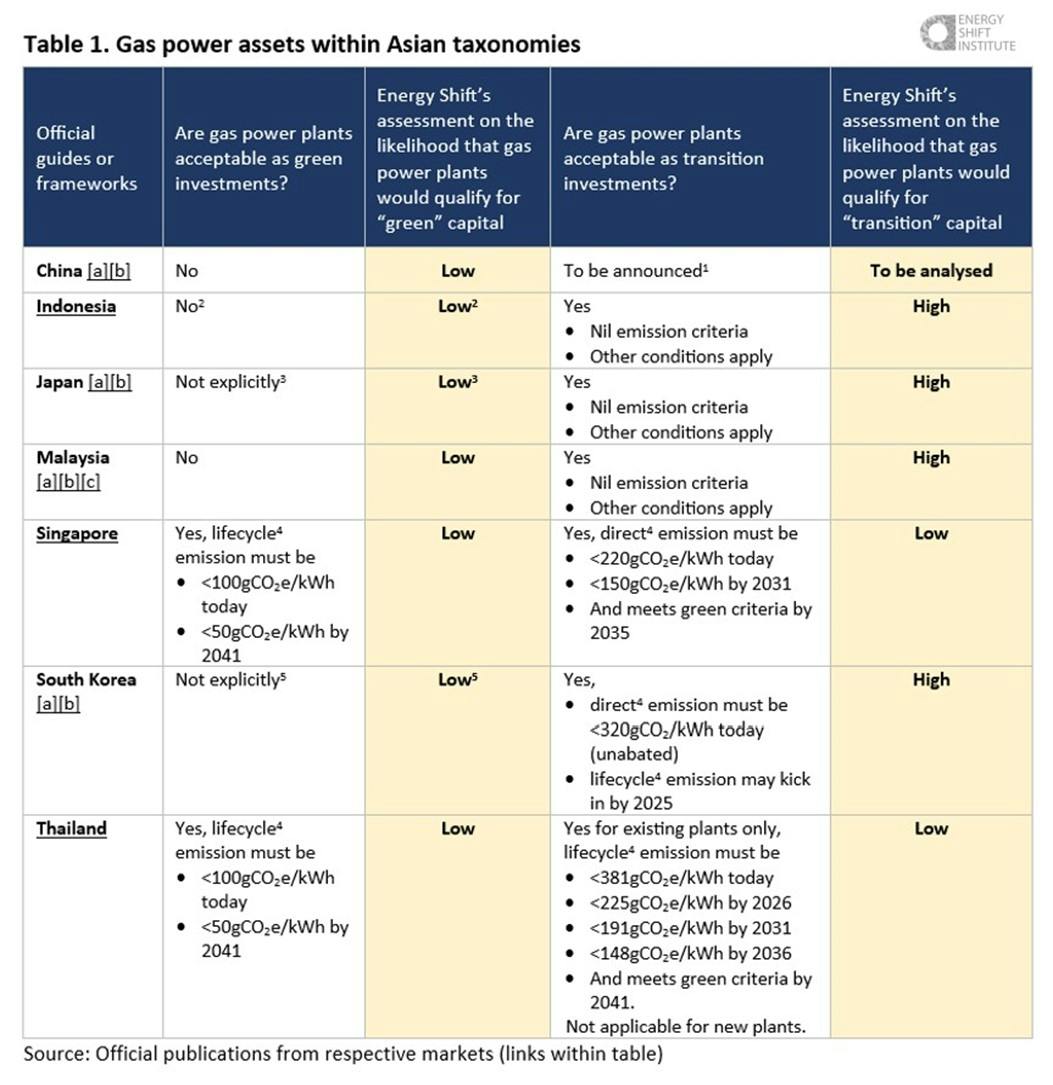

Table 1 shows the specifications at which gas power plants are treated as green or transition investments in Asia.

Among Asian countries, Singapore and Thailand have sustainable financing taxonomies that offer a more balanced ways to deal with emissions from the gas sector, said Christina Ng, managing director at the Energy Shift Institute. Image: Energy Shift Institute

While not many markets label gas as “green”, most are happy to explore gas-powered generation as a “transition” investment, although Singapore and Thailand do this to a lesser extent. Meeting the taxonomy’s definition of “transition” enables capital to be raised for new or existing gas plants via transition bonds or loans, including those branded “sustainability-linked”. As such, emissions-conscious investors would need to be on higher alert to transition-themed finance, which the investment community is otherwise excited about.

Like the EU, Singapore and Thailand have gone down an interesting route. Their taxonomies recognise that it would be hard to meet strict thresholds, but if there is a way to produce zero or low-emission gas-fired energy, then it is welcomed under the green or transition labels. This appears to be a more balanced way to deal with gas lobbyists, both producers and users, and puts the onus back on companies to find an “emissions-free” version of their product.

In other words, if gas players want to avoid paying a premium for financing, then they must start investing more heavily in real technological advancement, particularly in the areas of carbon capture and storage (CCS). At time of writing, we are not aware of any operating CCS for gas-powered generation in Asia.

It is notable that both Japan and South Korea have a looser stance on gas, which is disappointing given that their higher development status within Asia should otherwise see them demonstrate regional leadership in this area.

In particular, Japan’s power sector transition roadmap emphasises the reduction of carbon as a priority – placing methane on the back burner – and does not offer an emissions guideline, a backward move that remains in lock-step with emerging market counterparts, unlike Singapore and Thailand. The government’s support for gas-fired plants as a transition investment has facilitated the issuance of transition bonds and loans amounting to over 170 billion Japense Yen (US$1.13 billion) by utility companies,such as JERA, Kyushu Electric Power and Osaka Gas. Most of the proceeds were allocated to refinancing existing or building new gas power plants, according to respective official company documents.

South Korea also focusses on carbon reduction. While it has a cap on carbon emissions, it recognises unabated gas plants as green-transition investments until 2025 (unless extended). This is a lower standard as compared to, for example, Singapore and Thailand, which require all greenhouse gases to be measured, necessitating an emission abatement technology like CCS at gas power plants.

When markets like Japan and South Korea are already reliant on gas power, it is questionable what these economies are really transitioning to. Would more unabated gas investments make sense as a transitionary step to reducing emissions?

Short-term environmental cost

In principle it makes sense that gas is a transition fuel for some markets. However, embedding this narrative at COP28 seems to be legitimising the position of gas in financial markets and allowing it access to more abundant and cheaper capital than it otherwise could obtain.

The affordability of gas-powered electricity has been a persistent issue for many Asian emerging markets, especially those relying on imported liquefied natural gas, so this should challenge the transition fuel notion. Those who can afford to pay for gas should proceed with it if they really need it, but in the absence of regulation that limits new gas investments, it should be left to the power of market forces to determine its financing, without the help of a green or transition label.

Embracing gas in taxonomies is a concerning experiment in encouraging the gas industry to evolve or change its behaviour – the recent u-turn in renewable energy investment pledges has demonstrated a bad track record of following through. A more realistic outcome is that it risks locking emerging markets into a high-emissions future because any gas-powered project invested in today will have a 20 to 40 year lifespan.

Investing in more gas facilities comes at a cost to the environment or climate in the short term. It makes sense that gas developers and power operators should be finding it increasingly difficult and costlier to source capital. This justifies the externalities gas creates.

Christina Ng is managing director of the Energy Shift Institute, an independent non-profit energy finance think-tank driving context, clarity and credibility for Asia’s energy transition pathways.

This op-ed was first published on Energy Shift Institute.