Cocoa is probably the most sustainable of all internationally traded commodities, so there are several “feel-good” reasons for eating the chocolate made from it this Easter—at least when the cocoa is grown by smallholder producers and traded by processors that are committed to equitable sharing of profits.

Here are some ways to tell if you are onto a good thing.

Environmental impact

As a wild species, cocoa (Theobroma cacao) originates from the rainforest of the Amazon basin and the foothills of the Andes. In nature, it grows as an “understorey” species, shaded by the rainforest canopy. Much of the world’s cocoa crop is similarly grown in the shade of taller trees in mixed plantings.

Unlike many plantation crops, like rubber and oil palm, cocoa can be grown with a diverse mixture of other plants. Of course, not all growers produce this way, so if preserving biodiversity is a priority for you, look for Rainforest Alliance certification.

Healthy cocoa, grown in an agroforestry system with minimal chemical inputs, in Fiji. The cocoa beans are in the yellow pods. Image: Richard Markham

Cocoa needs a lot of water to survive, so large irrigated plantations have a high water footprint. On the other hand, almost all smallholder cocoa is grown without irrigation in high-rainfall areas, so the water used in production of the cocoa is close to zero (apart from a small amount of water used in processing).

Another environmental aspect is the use of fertilisers and pesticides. When cocoa pods are harvested they take a lot of nutrients with them, out of the ecosystem. On average, a kilogram of dry cocoa contains 36 grams of nitrogen, 6g of phosphorus, 72g of potassium, 7g of calcium, and 6g of magnesium.

This means maintaining soil condition is critical. This can be achieved with careful application of fertiliser, though this rarely occurs and soil depletion has become a major problem prompting aid groups to encourage more fertiliser use!.

However, research in Sulawesi, supported by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research and chocolate giant Mars Inc, has shown that using a judicious combination of nitrogen-fixing shade trees and compost (ideally produced with the help of goats) can maintain soil fertility—and even reclaim depleted speargrass savanna—for cocoa production.

“Trials by Indonesian and Australian researchers in Sulawesi suggested that a combination of compost and inorganic fertiliser gave the best results. Image: Richard Markham

Research trials on sustainable cocoa production at the ‘Mars Academy’ research station in Sulawesi, Indonesia.Image: Richard Markham

Finding good chocolate

The good news is that there are plenty of chocolate producers who avoid all of these problems. There are two ways to find it: look for certifications, or seek out small operations in our region.

Fairtrade certification means that smallholder producers in developing countries are getting a fair share of the price you pay.

Rainforest Alliance certification, meanwhile, ensures that rainforest hasn’t been cleared to make way for unsustainable plantations.

If you’re concerned about fertiliser and pesticide use, UTZ (who have recently merged with the Rainforest Alliance) has built sustainable productivity into their certification systems.

All of these certification schemes are largely available to multinational companies. Some of the biggest chocolate companies in the world, including Mars, Ferrero, Hershey and Nestlé, have committed to sourcing 100 per cent certified cocoa, so it’s possible to buy sustainable cocoa without even realising it.

On the other end of the scale are smallholdings, which are likely to lack these kinds of certifications. That doesn’t always mean they are bad for the environment, or that the growers aren’t getting a fair price. It may simply be that the expense of formal certification is not worth it for many small operations.

Much of this chocolate is organic more or less by default, as many smallholders, especially in the Pacific region, simply do not use agrochemicals. It’s also more likely to be grown in heavily rainforested areas, with almost zero water footprint.

“

With a bit of attention to the back story, you can enjoy a whole range of delicious new chocolate experiences this Easter—and feel that you are contributing at the same time to the equitable and sustainable development of the planet.

In their search for high quality and unique flavours, several Australian boutique chocolate makers have started to source their beans directly from cacao growers.

For instance, Bahen & Co. in Margaret River, Western Australia, purchases beans directly from communities on Vanuatu’s Malekula island, while Jasper & Myrtle in Canberra buys beans from growers on PNG’s previously troubled island of Bougainville.

These programs mean that these growers have been able to taste chocolate from their own beans for the first time, and thus understand how their own processing of the beans—through fermentation and drying—affects the quality of the final product.

Australian chocolate maker Mark Bahen evaluates samples of beans from individual growers in Vanuatu.Image: Conor Ashleigh for ACIAR

Even more value can remain with the local growers and their communities if the chocolate itself is manufactured in-country. Visitors passing through duty free shops as they leave PNG may have picked up Queen Emma chocolate, made by Paradise Foods in Port Moresby, while those leaving Nadi may have bought Fijiana chocolate made by local company Adi’s Chocolate.

Australian shoppers will soon be able to buy Aelan chocolate – single-origin bars from four different islands of Vanuatu, made in Port Vila by ACTIV, a Victorian NGO founded and operated on fair-trade principles.

At the furthest end of the fine-flavour chocolate trend are chocolate bars with no artificial additives of any kind. A favourite recipe among discerning chocolate-tasters is simply to mix 80 per cent cocoa “nibs” (coarsely ground beans) with 20 per cent sugar and “conch” it gently until smooth and delicious.

Drying cocoa beans in the sun helps to develop the best flavour (in this case Kerevat, PNG) Image: Yan Dicbalis

What about food miles and the carbon footprint?

The typical cocoa bean from the Asia-Pacific region is bought by the local representative of a global commodity trader. It is shipped to Singapore, or directly to Indonesia, which has the capacity to grind some 600,000 tonnes of cocoa each year. The ground or whole beans then travel onward to Europe.

Belgium has a well-established reputation as the world’s preferred provider of “cocoa liquor”, and some of this is shipped back to Australia as the raw material for local chocolate manufacture – now with a sizeable carbon footprint.

Other beans will be shipped to France, Italy, Switzerland (or will remain in Belgium) for manufacture into delicious chocolates, and some of these too will be shipped back to our region for retail sale. If fossil fuels and global warming are among your concerns, consider seeking a chocolate product that was grown and processed nearby.

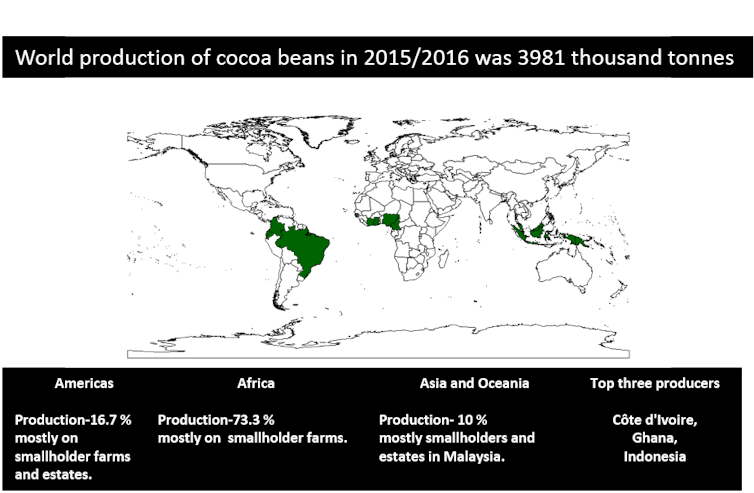

The big players are Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Indonesia, with small amounts of smallholder-dominated production in the Pacific. Image: ICCO, 2017. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics. Vol. XLIII, No. 3. Cocoa year 2016/17. International Cocoa Organization, London

![]() In sum, with a bit of attention to the back story, you can enjoy a whole range of delicious new chocolate experiences this Easter—and feel that you are contributing at the same time to the equitable and sustainable development of the planet.

In sum, with a bit of attention to the back story, you can enjoy a whole range of delicious new chocolate experiences this Easter—and feel that you are contributing at the same time to the equitable and sustainable development of the planet.

Robert Edis is Soil Scientist at the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; Kanika Singh is Research Fellow at the University of Sydney, and Richard Markham is Research Program Manager for Horticulture at Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. This article was originally published on The Conversation.