In the popular media and the business world, urbanisation is often cited as the fundamental driver of global economic growth, especially for the next few decades.

The assumption is that a rural–urban shift will transform poor farmers into industrial and office workers, raising their incomes and creating a massive consumer class. Imagine farmers who once led simple, subsistence lives becoming workers in the city, buying up apartments and furnishing them with appliances.

Not surprisingly, China has been considered the poster child for this linear model of rural–urban shift and accompanying inexorable consumption growth. To the China ‘boomsayer’, even more impressive consumption is yet to come: another 300–400 million rural dwellers will be converted into city folks in the next 15 years. Prepare for China’s urban billion, advises McKinsey & Company. Think about how many millions of new apartments and how many cities like Shanghai will be needed for all these new arrivals; how many more Ikea-like home furnishing stores? The list goes on.

If one simply looks at the number of people relocating, China is indeed undergoing rapid urbanisation. But while its epic rural–urban shift has many of the trappings of what amounts to contemporary urbanisation elsewhere in the world, urbanisation in China is a more complicated phenomenon that requires a deeper understanding beyond the superficial, one-dimensional narrative.

Present-day China’s urbanism can be quite deceiving as the statistics are often misleading, and city bureaucrats excel at choreographing window-dressing ‘image projects’ and sequestering poverty. Most important of all, behind China’s sparkly modern, urban facade there is one crucial foundation of its prosperity that is unique in modern times and continues to be largely ignored by the business literature: China remains an institutionalised two-tier, rural–urban divided society. This is a consequence of Mao-era social engineering that continues to this day. This division not only manifests itself in economic and social terms, as in many Third World countries in the throes of urban transition, but is also tightly enforced, mainly through a system of hereditary residency rights, called the hukou.

The hukou system has created two classes: on the one hand, an urban class whose members have basic social welfare and full citizenship; on the other, an underclass of peasants with neither of these privileges. In Mao’s era, peasants, forbidden to go into the cities, were confined to tilling the soil to grow food for urban workers. With China’s opening up and participation in the global economy, peasants have been allowed to come to the city where they are compelled to take up low-paid factory and service jobs. Many of these are dirty and dangerous. At the same time, peasants are denied access to urban welfare programs and opportunities because the great majority of them are not allowed to change their hukou from rural to urban.

‘Rural migrants’ work and live in the city but they are not part of the urban class — not now and not in the future, no matter how many years and how hard they have worked in the city. This group now numbers about 160 million and continues to rise. The fact that they are purposely held down as a massive permanent underclass is precisely what supplies China with a huge, almost inexhaustible pool of super-exploitable labour. Little wonder that China is the world’s largest — and the most ‘competitive’ — manufacturing powerhouse!

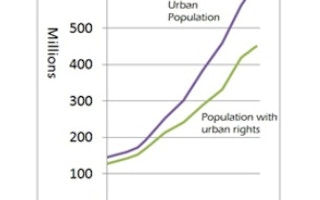

China’s rapid urban population growth trend, as represented by the blue line in the graph below, is all too familiar. But that single-line description has left out an important point: the majority of migrants to the city do not have urban rights. Alarmingly, the gap between the total population living in cities and the number of those who possess urban rights (the green line) has widened as the country moves forward.

Graph showing the growing percentage of China’s urban population without urban rights.

That expanding gap represents the great number of people who are in the city but not of the city. They receive nothing from the ‘benefits package’ assumed to be associated with urbanisation: better housing, better educational opportunities and health care. With meagre wages and no chance of legally settling in urban areas, they also lack an incentive to invest in a future in the city. They will not spend on major appliances in a place that does not want them. In fact, most migrant workers do not have the purchasing power that would position them even to dream of any decent housing in the city. Most remain crammed into dormitories or consigned to the Chinese equivalent of slums — the ‘villages in the city’, where they must eke out their living on the urban fringes.

Far from becoming the new consumer class, they form a mammoth underclass whose size will easily swell to 300–400 million in a decade. This will have serious implications. For the moment, it must be understood that this class has nothing to do with China’s recent housing boom other than by providing muscle power at building sites.

When examining the notion of urbanisation as the path to rapid consumption expansion, it is clear that its relevance to China, under its current configuration of economic and legal inequities, has to be hugely discounted. There are many myths behind the perception and sustainability of China’s recent economic rise. Urbanisation remains one of the biggest.

An earlier version appeared in China-USA Focus on 16 July, 2011. Kam Wing Chan is Professor at the Department of Geography, the University of Washington. Visit his home page for more commentaries and articles.