The Covid-19 pandemic has sent shockwaves through the global energy economy. Wealthy countries have scrambled to quickly inject money into their economies, supporting many businesses and looking for opportunities to “stimulate” demand.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Countries with large development debt burdens and less space on their budgets have found it much harder to cushion their people from the blow.

Nigeria, facing cuts to government spending of 25 per cent, will now fall deeper in debt so it can deal with the Covid-19 crisis. Iraq’s salaries and social benefits, funded 90 per cent by oil revenues, will inevitably be slashed this year. Hobbled by budget cuts, Ecuador has struggled even to bury the dead.

Manufacturing activities in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines have contracted sharply. In the Philippines, with about a-tenth of its gross domestic product coming from overseas remittances, layoffs in rich host countries such as the United States, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia threaten the welfare of millions of low-income families depending on money from migrant workers to afford basic needs.

In China, the impact of the coronavirus outbreak on the economy is still only beginning. A prolonged shutdown of business operations would devastate the economy, with the recreation, transportation, trade and communication services the hardest-hit industries .

However our response to the Covid-19 crisis will not only be determined by how we react to the urgent economic emergency—it will also depend on how the policy choices made now set up our economy for the future.

If politicians respond only with short-term vision, or to the loudest lobbyists asking for a bailout, then the economic response won’t prepare us for the coming climate crisis—and importantly, for the disruption that climate action is already bringing to the coal, oil and gas sectors.

The end of the fossil fuel era is likely to happen this decade. Oil has already dipped below zero.

Investors are tossing coal out faster and faster. Gas has been one of the sectors hardest hit in the Covid-19 recession and is using all of its political connections to stay afloat.

Which brings us to the question: How do we effectively and fairly plan for this massive change in our economic structure? A new academic paper answers that question. The report co-authored by the Stockholm Environment Institute proposes five principles for fairly managing the social challenges of phasing out fossil fuel extraction:

1. Phase down global extraction at a pace consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.

At current rates of emissions, the carbon budget for 1.5°C will last barely a decade. Fossil fuel use needs to be wound down quickly to avoid hitting those limits, and largely phased out this decade.

2. Enable a just transition for workers and communities.

The labour movement has led in fleshing out what a just transition entails: Creating decent new jobs (i.e. with fair pay, reasonable conditions and union rights) by investing in alternative sectors; retraining transition-affected workers to help them get alternative jobs; protecting the rights and income of workers and communities throughout the transition; and democratically engaging those stakeholders in the process of transition.

3. Curb extraction in ways consistent with environmental justice.

In line with environmental justice, ending fossil fuel extraction should be prioritised where pollution destroys livelihoods and health. In cases where extraction violates people’s rights, it should be reformed or stopped immediately.

These first three principles shape the overall scale of a global transition, and provide essential guidelines for any given country, region or sector. But the next question is how do we think about this transition globally. The following principles help with that:

4. Reduce extraction fastest where the social costs of transition are least.

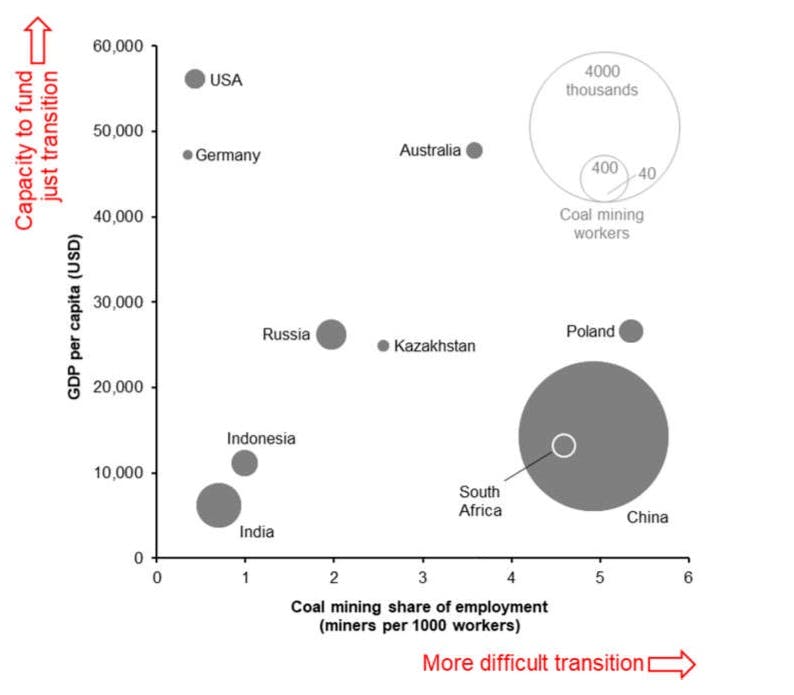

Achieving the Paris goals requires all countries to wind down fossil fuel extraction and use. But this does not mean all must phase out at the same pace, or make the same efforts. A phaseout will be more socially impactful in countries with high economic dependence on fossil fuels and with limited economic resources to manage it. Wealthier countries should thus phase out extraction fastest.

5. Share transition costs fairly, according to ability to bear those costs.

Since the costs of mitigating climate change are incurred for the (global) common good, they should be shared fairly. The largest burden should be borne by those with the broadest shoulders, rather than by those unfortunate enough to be most directly affected.

To illustrate, consider coal mining in Germany compared to China. Coal miners account for 0.03 per cent of Germany’s workforce, compared to 0.6 per cent of China’s. As a proportion of the national workforce, China’s challenge is thus 20 times the size of Germany’s. Moreover, Germany’s coal mining wage bill amounts to 0.03 per cent of GDP; China’s to 0.5 per cent.

Assuming the costs of a just transition (such as retraining and social protection) are proportional to the wage bill, this suggests that Germany has 16 times greater economic resources than China, relative to what is needed.

Germany and China thus differ along two important dimensions: The relative scale of the transitional challenges, and the countries’ ability to mitigate and absorb its adverse impacts. The graph below shows the 10 largest coal-extracting countries on these two dimensions.

The varying capacities of countries to fund a just transition.

Oil and gas extraction are less directly labour-intensive than coal, but often indirectly support a larger public-sector workforce through government revenues. In Algeria, for instance, oil and gas account for 34 per cent of government revenue and funds the salaries of about 1.7 million workers, or 14 per cent of Algeria’s workforce. In several developing countries, the share of government revenue is even higher.

Last year’s Production Gap Report, produced with guidance from United Nations Environment Programme staff, showed that governments’ plans for fossil fuel extraction massively exceed what would be aligned with the Paris Goals, and yet the beginning of this year has shown the weakness of the fossil fuel industry. Too often, governments hide behind a global target, leaving it to others to cut back. This new report gives us principles by which the global limits might translate into national and regional change.

Conversely, given the limited carbon budgets, fossil fuel extraction cannot be a viable pathway to socio-economic development: It would instead leave countries with a legacy of stranded assets and unmet liabilities. All countries should begin a phaseout, though poorer countries may move at a slower pace and may require international support.

If a breakthrough is to be politically possible, the task must be approached fairly. And while the initial response to Covid-19 has shown how not to equitably manage the decline of fossil fuel extraction, it has shown the need for a different approach. Now, it is a matter of who has the political will to show up as a true climate leader and take on the task.

Norly Grace Mercado is Asia regional director at 350.org, an international movement to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy. This opinion article oped was based on a paper by Gregg Muttitt, an energy and climate change research, and Sivan Kartha of the Stockholm Environment Institute.