More than three people were killed every week for trying to protect their land, forests and rivers against industries last year, with Southeast Asia emerging as one of the most dangerous regions for environmental activists.

To continue watching, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The new report by international campaigning group Global Witness, titled On Dangerous Ground and released on Monday, documented 185 known killings worldwide in 2015, making it the worst year on record for the murder of environmental and land defenders.

But severe limits on information “mean the true numbers are undoubtedly higher”, said the group.

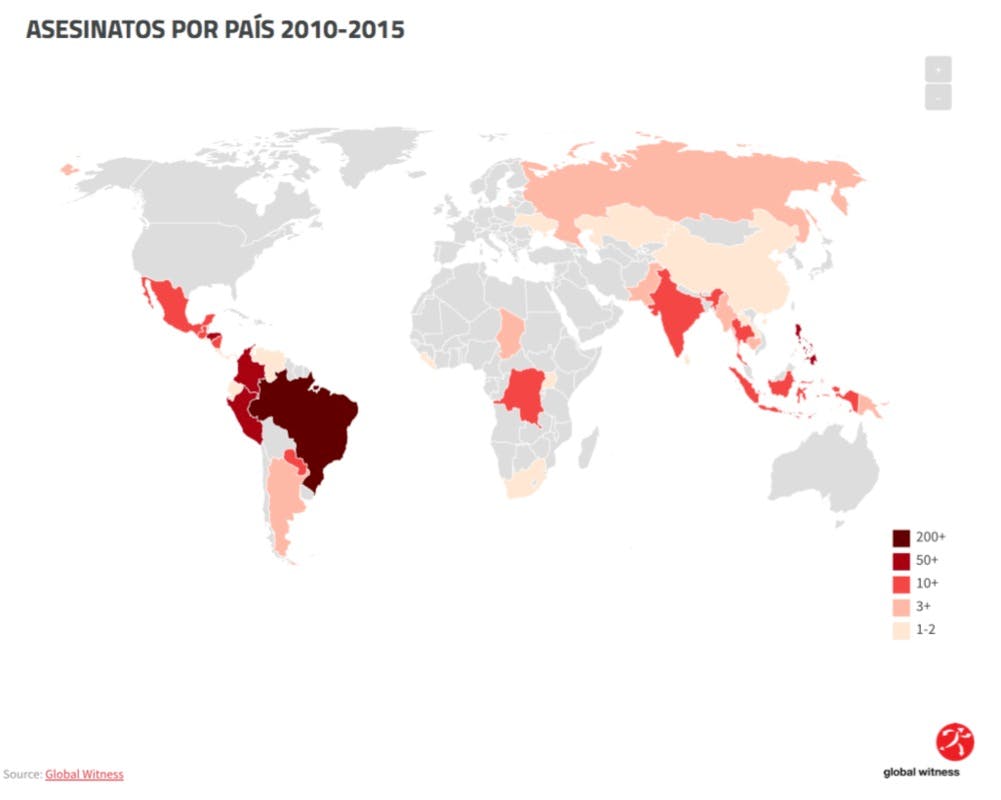

Brazil was the deadliest country for environmental protestors, with a record 50 activists murdered last year. Philippines came in second, with an unprecedented 33 killings. Across Southeast Asia, three deaths were documented in Indonesia in 2015, with two murders each recorded in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand.

These figures are a 59 per cent increase from killings in 2014, said Global Witness, and almost 40 per cent of the victims were from indigenous groups.

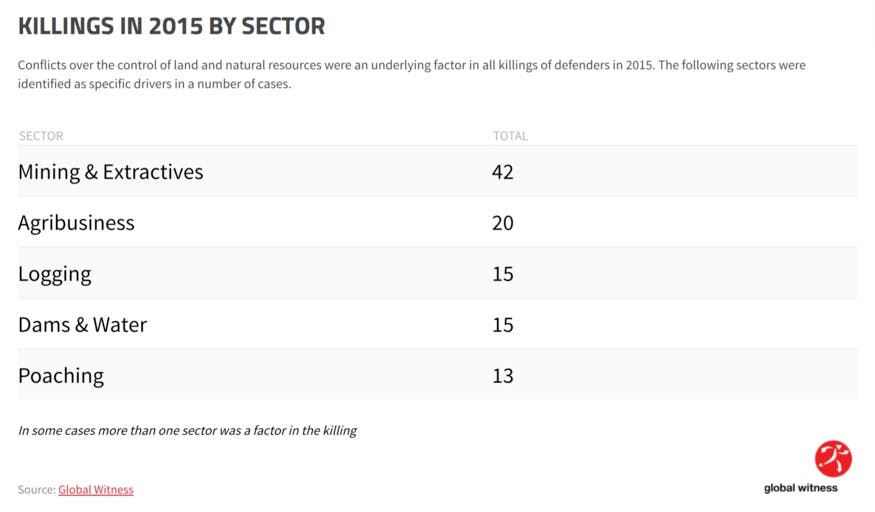

The mining industry was one of the biggest drivers of the killings, accounting for 42 of the 185 deaths. Agribusiness and logging together accounted for 35 deaths, while hydropower projects were linked to another 15 deaths.

2015 killings by industry. Image: Global Witness

Billy Kyte, Global Witness’ campaign leader, said in a statement that “as demand for products like minerals, timber and palm oil continues, governments, companies and criminal gangs are seizing land in defiance of the people who live on it”.

“Communities that take a stand are increasingly finding themselves in the firing line of companies’ private security, state forces and a thriving market for contract killers,” he added.

Among the horrific murders was the public execution and torture of Filipino anti-mining activist Dionel Campos, his father, and a local school principal in Mindanao, Philippines last September.

With rich nickel and coal deposits, Mindanao is the most dangerous areas in the world for environmentalists, accounting for 25 deaths last year alone.

Those who saw the Campos killing said the three men had been killed by a paramilitary group working with the national army. According to Global Witness, United Nations experts called on the government to launch a full and independent inquiry, but to no avail.

Michelle Campos, daughter of the activist, said in the report that “we get threatened, vilified and killed for standing up to the mining companies on our land and the paramilitaries that protect them”.

“We know the murderers – they are still walking free in our community,” she added. “We are dying and our government does nothing to help us.”

Last July, Burmese land rights advocate Saw Johnny was shot multiple times by unidentified gunmen while a month before that, Indian journalist Sandeep Kothari was found burned and beaten to death in the state of Maharashtra, India. Kothari had written about a sand mining mafia operating in a neighbouring state.

In Brazil, illegal timber logging in the Amazon rainforest was responsible for many of the deaths recorded by Global Witness. Criminal gangs, bankrolled by timber companies, illegally harvest mahogany, teak, and ebony from the endangered forest, said Global Witness.

The NGO estimates that about 80 per cent of all timber originating from Brazil is illegal, and that much of this is sold on to consumers in the United Kingdom, United States, China and Europe.

World map of activist murders. Image: Global Witness

Global Witness noted that very few of the murderers were ever brought to justice, as governments failed to properly investigate these crimes and prosecute anyone for them. This is likely due to collusion between corporate and state interests, the NGO suggested.

It pointed to the strong role of paramilitary groups, the army, police, and private security firms in the killings - these groups accounted for 51 of the 185 killings - as evidence of state or company influence over the killings.

Even as governments drag their feet on investigating the activists’ murderers, the criminalisation of protest is on the rise, found Global Witness. In Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, governments are silencing dissent by branding activists as “anti-development”, and in some cases, imprisoning them.

For example, Global Witness documented the case of Armand Marozafy, an activist from Madagascar, who was given a six-month jail sentence and US$4,000 fine last year for denouncing illegal rosewood trafficking in the country in an email that was later leaked on social media.

“Governments must urgently intervene to stop this spiralling violence,” said Global Witness’s Kyte.

Policymakers in affected countries should increase the amount of protection available for land and environmental activists who are at risk, and should investigate crimes so that perpetrators are brought to justice, urged the group.

Governments should also ensure that companies are proactively seeking the free, prior, and informed consent of communities before proceeding with projects on their land, and respecting their decision if they decline to grant access, Global Witness recommended.

The underlying causes of violence - a lack of formal recognition of indigenous community’s rights to land, and corruption in the natural resource sector - also must be addressed, the report said.

As for the private sector, companies and investors should not only refrain from harassing and intimidating environmental defenders, they should also proactively establish grievance mechanisms to address and investigate human rights abuses in their operations, said Global Witness.

All companies should also adhere to the UN’s Voluntary Principles on Human Rights and Security, as well as Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, it added.

But for now, the killings continue. In March, the murder of high-profile Honduran environmental campaigner Berta Caceres sparked a global outcry. Caceres, who was the recipient of the prestigious Global Environmental Prize which recognises grassroots conservation efforts, had been a vocal opponent of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam.

She was shot dead in her home, after having reported more than 30 death threats linked to her campaign, and warning officials that her name was on a hit list given to the military police. Among the men arrested for her murder was a then-active Honduran official, Mariano Diaz Chavez, who has since been dishonourably discharged.

“This is a rapidly growing crisis that is showing no signs of abating,” said Global Witness. As climate change and population growth place continue to put pressure on land and natural resources, “without urgent intervention, the numbers of deaths we’re seeing now will be dwarfed by those in the future”.